By: Manapee Khongrakchang

6 / February / 2026

I first travelled to the Mae Ngao village in July 2022. It was rainy season, gray and humid. There I met the Riverside People, a fisherman and a knowledge holder of Mae Ngao villagers who was struggling but kept telling stories about how the Mae Ngao people, a marginalized community of ethnic Muang and Indigenous Karen groups, had disagreed with the Bhumibol Reservoir Inflow Augmentation Project and suffered injustices during the environmental impact assessment. Although community protests against various dams on the Salween River since the 1970s are often interpreted as “anti-development” (Hengsuwan, 2019), the fight against this proposed water diversion project continues. On October 18, 2023, a group of Mae Ngao villagers and Salween civil networks petitioned the Administrative Court in Chiang Mai to cancel the Bhumibol Reservoir Inflow Augmentation Project, or the Yuam water diversion project, because it is flawed and illegitimate. The preparation and development processes were flawed from the beginning until approval. Afterward, the court decided to take up the case on January 19, 2024 (B. Tribune, 2023; 2024). Nevertheless, the case is still pending in the Administrative Courts of First Instance even in early 2025.

On that day, the Riverside People grabbed me on his boat and asked me about myself. After knowing that I was studying about the case of the water transfer project on Mae Ngao River for my master’s thesis on the Ethnicity and Development program in the Faculty of Social Sciences, Chiang Mai University, he asked a significant question that hit me hard: “What do you think about sustainability? What does sufficiency mean for you?” I was stunned then because several discourses were clashing in my mind. While I was still quiet, he paused and told me not to answer until after we finished the site visit.

He and his son took me to Huay Nam Daeng, where several sizes of big rocks lay side by side (see Figure 1). We travelled until we could not go further due to the mighty river flowing harshly through the rocky rapids. He pointed to those big rocks and told me that the scenery would vanish under the dammed water if the water diversion project passed governmental approval. He explained that though we humans were tiny compared to nature, human creatures hurt the earth the most in our era. This period is known as the Anthropocene, and it can refer to either a planetary form or the history of how humans changed nature, wiped out other species, interfered with ecosystems, and then transformed the planet. Humans are small but powerful enough to destroy the mountains, move the river, and disrupt other beings, especially those who are different from the majority or power-dominant groups.

The question the Riverside People asked me about the meaning of sustainable living echoed with the song of the rocky rapids at Huay Nam Daeng, reminding me how the water diversion project would disrupt the ways locals lived. Hengsuwan (2019) explains how the state controls people and natural resources with the terms “development and civilization,” while categorizing alternative livelihoods as “anti-development,” In front of the rapids, I wondered what it would take to control native living beings in an environment with abundant in natural resources, and why minorities and nature seemed to always be the ones who sacrifice for “Growth”? We know that global climate crisis is destroying the earth and its ecosystems. While many countries have signed on to the SDGs, or Sustainable Development Goals, it seems we still cannot get enough of GDP. While the sustainable future in action for SDGs are some ticks in boxes indicating some surface implementations for sustainability, the dam and water diversion project was framed as Green Energy for Green Economy. Was it sincerely ‘green’ or just greenwashing? Was it healthy or desired by the natives of those lands we took, and the other places we will take, in the name of growth and development? These questions haunted me and I still could not answer his question about sustainability.

Figure 1: The large rocks at Huay Nam Daeng in comparison to a human scale.

We jumped across big rocks and landed on a flat one, where the Riverside People showed me the ‘Cultural Mapping’ posters that collected local ecological knowledge about the river, its species, and the village habitats and livelihoods, which were co-produced through the Mae Ngao villagers’ work with the Center of Ethnicity Studies and Development (CESD), Chiang Mai University. The local ecological knowledge shown through Cultural Mapping is based on the Yuam-Mae Ngao River ecosystem as an attempt to speak out to power about the recognition injustice and distributive injustice that happened in the revised study of the Environmental Impact Assessment for the Bhumibol Reservoir Inflow Augmentation Project, also known as the Yuam Water Diversion Project. One aspect he showed me was how the water diversion project will destroy the natural fish ladder formed by the rocky riverside and the rocky riverbed (see Figures 2 and 3), which let fish travel from the downstream Salween River basin into the Mae Ngao River.

Figure 2: The rocky riverbed, captured in this underwater photograph, serves as a natural fish ladder, allowing fish to migrate from the Salween river basin into the Mae Ngao river

Figure 3: The rocky riverbed, visible from above, forms a shallow stepping terrain that creates strong flows. These flows, highlighted by white foams and the interplay of light and shadow, indicate powerful currents moving over the rocks underwater, essential for the river’s ecological dynamics.

As the Mae Ngao fishermen have seen the bruises and scratches on the fish’s skin, they know these fish are the fighters traveling through rocks and strong currents to continue their species in the clear water and pristine river of Mae Ngao. One fish that travels far from the Andaman Sea, the Bay of Bengal, in the Indian Ocean, is the Mottled Eel, which is called ‘Sa Ngae’ in Northern Thai or ‘Lha Htee’ in Karen Language (see Figure 4), with the scientific name Anguilla bengalensis. Sa Ngae are catadromous fish that migrate from rivers to seas for breeding. As a long-distance migratory tropical freshwater eel, it breeds in the ocean. It migrates into freshwater, up to rivers and streams far upstream of the Nu-Salween River Basin in China, to mature in pools. Due to their dependency on the longitudinal connectivity of large rivers, many of which are fragmented, they are vulnerable and are declining toward extinction (Ding, et al., 2023; Sinha, et al., 2018). While people have different views on several aspects from the EIA report, all agree that if the proposed dam and water diversion project were located here, the mottled eel would become extinct from the Mae Ngao River.

Recent investigations reveal that parts of the Salween River now contain arsenic and lead above safe levels, largely due to unregulated mining along the basin, effecting people’s livelihoods and other species (Transborder News, 2025a, 2025b; Bangkok Post, 2025). As contamination spreads through the Salween system, the Mae Ngao and Yuam River—one of its clean upper tributaries—has become one of the last clear refuges for fish, wildlife, and the people who depend on it. If a dam is built here, it will cut the final safe pathways many species rely on to survive.

Figure 4: A fisherman in Mae Ngao holds a juvenile mottled eel, its vibrant yellow hues hinting at the grey it will develop in maturity. This species, reliant on the river’s longitudinal connectivity, faces a precarious future due to fragmentation and ecological threats.

The locals hold a deep understanding of their environment. Ecological knowledge is passed down through generations —shared among friends, fishermen, sisters, and parents with their children. Learning occurs organically through oral storytelling, traditions, rituals, play, and observing elders. There is no physical classroom, but the place is their school of life, which gives knowledge with experiences and living resources. Building on Karen Barad’s concept of Intra-Action (Kleinman & Barad, 2012), I describe the strong interconnection between the Mae Ngao people, their environment, and more-than-human agencies as a form of kinship.

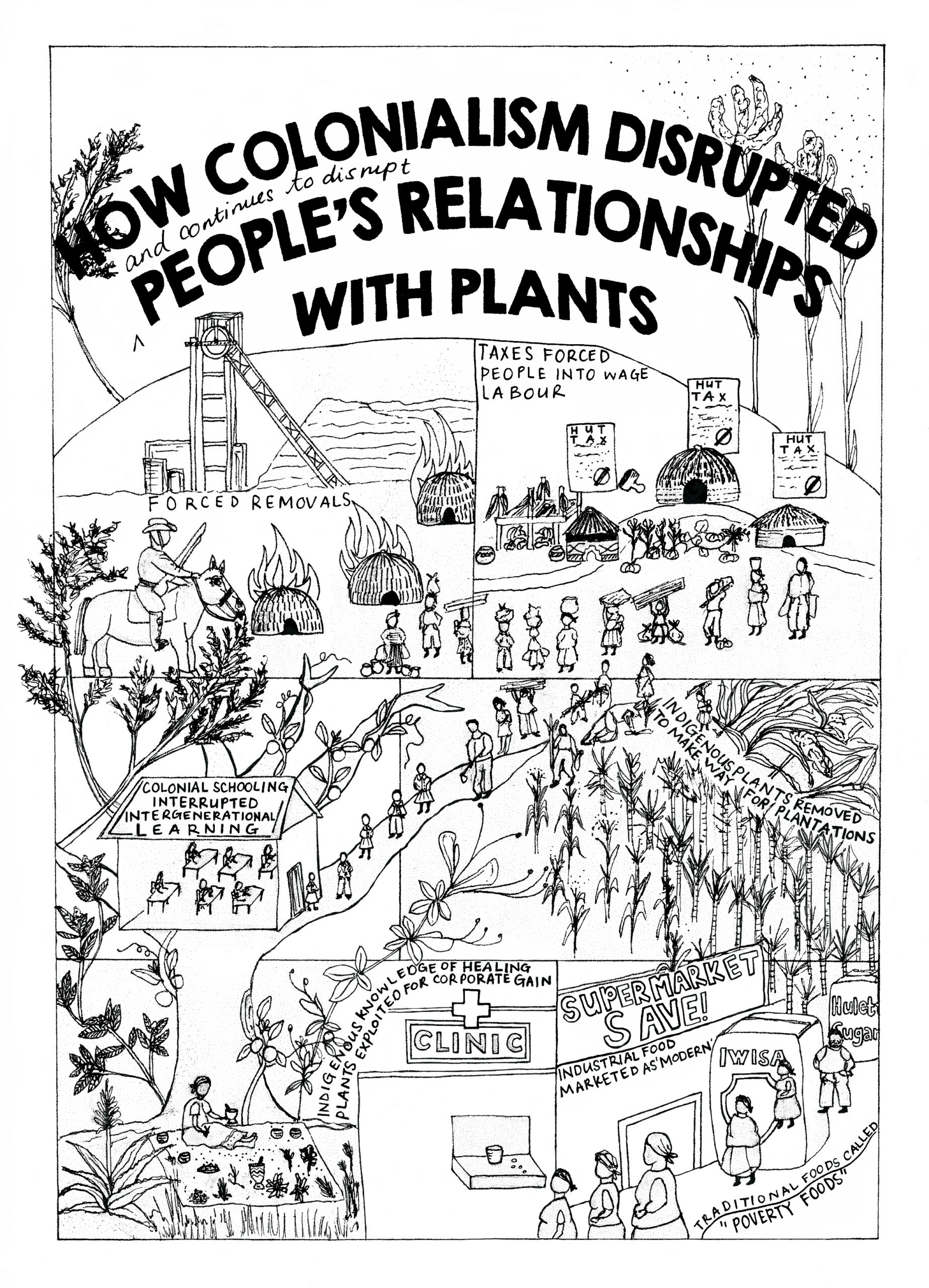

I initially questioned why the villagers of Mae Ngao held such a deep connection to their rivers and creeks. This was clarified during later fieldwork in 2022 when I returned as an observer and a translator for Antonia Mohr, a master’s student from Germany researching hydro-politics in the region. We engaged with villagers to understand the river’s significance, observed their livelihoods during our stay, swam in the river, gathered food with children in a creek (see Figure 5), and travelled by boat along the Mae Ngao and Yuam Rivers. All the participants in Antonia’s research answered that the river is life for them (Mohr, 2022). The villagers’ actions in Mae Ngao reflected a profound kinship with nature, rooted in gratitude for the reciprocal relationship between humans and more-than-human agencies. Respect and reciprocity are central to their livelihoods, mirroring practices in many indigenous communities. However, this kinship has been eroded by modernization, the imposition of national languages, resource extraction, and land grabbing justified as development (Whyte, 2020). We have been losing this kind of kinship in many places worldwide throughout colonialism and capitalism, and we will lose it forever in the Mae Ngao River basin if the Yuam water diversion project proceeds.

Southeast Asians have been colonized spatially and mentally, but Mae Ngao villagers are practicing everyday resistance through meaningful livelihoods and speaking truth to power. Simple actions are their way to decolonize the power of dominant narratives on development and greenwashed sustainable futures. In ‘Decolonization is not a metaphor,’ Tuck & Yang (2012) explain:

“[D]ecolonization is not obliged to answer those questions – decolonization is not accountable to settlers, or settler futurity. Decolonization is accountable to Indigenous sovereignty and futurity. The answers are not fully in view and can’t be as long as decolonization remains punctuated by metaphor. —The answers will not emerge from friendly understanding and indeed require a dangerous understanding of uncommonality that uncoalesces coalition politics moves that may feel very unfriendly.” Tuck, E., & Yang, K. W. (2012, p. 36).

Figure 5: The photo captures children gathering food in a creek, portraying it as a playful activity that naturally embodies the transfer of indigenous knowledge across generations. This scene reflects the villagers’ deep connection to their environment, emphasizing respect, reciprocity, and a sustainable way of life.

On the first day I travelled with the Riverside People to Huay Nam Daeng, we caught two Devil Catfish (see Figure 6) and some freshwater shrimp. I was sitting next to the Devil catfish, thinking about the Riverside People’s proposed questions from the morning until the boat was almost back to the village. But he responded to his own question about sustainability and sufficiency, saying, “You see, we do not need much. We have enough for our needs. When I catch more fish than I can eat, I share them with others, just as I share fruits from home. In return, they share with me.” One fish and the shrimp are for sale, so his friends can buy petrol for his boat.

Figure 5: The photo captures children gathering food in a creek, portraying it as a playful activity that naturally embodies the transfer of indigenous knowledge across generations. This scene reflects the villagers’ deep connection to their environment, emphasizing respect, reciprocity, and a sustainable way of life.

“It is impossible for everyone to handle everything themselves,” he added. “Those skilled at fishing catch fish and share with others, who share their skills in return. This is what sufficiency means to me.” He continued, “We rarely use money; it’s unnecessary here. This is our sustainability—relying on nature as it is.” His words also reminded me of Robin Wall Kimmerer’s reflections in The Serviceberry (2024), where she describes a gift economy grounded in ‘enoughness,’ gratitude, and mutual care. What she writes feels familiar here: the Mae Ngao villagers live through exchange, not extraction; through reciprocity, not accumulation. Yet such an ethic cannot thrive if our minds remain shaped by the logics of overconsumption and endless growth. To truly imagine a sustainable and liveable future, we must first decolonize ourselves from the extractive economy that keeps telling us we never have enough.

Figure 7: The image shows the collision of the Mae Ngao and Yuam Rivers, where their waters merge in distinct hues. The clear, green-tinted Mae Ngao River flows over a rocky bed, contrasting with the brownish Yuam River, shaped by its sandy bed. This natural blending of colors symbolizes the diverse ecosystems of this area.

Not far from where the Yuam and the Mae Ngao rivers collided, exchanging two colors (see Figure 7), we finally arrived our last stop at the main bridge in the village. I thanked him and his son, carrying what I had learned in one day. Before we parted that day, I asked him, “May I buy a fish to pray merit for today?” He smiled lightly in response as permission. By releasing the fish back into the river, I hope it will become a part of the spirit protection for Mae Ngao River and her people, wishing for ourselves to decolonize our minds to achieve a more sustainable, inclusive, equal, and just future.

Bangkok Tribune. (2023, October 18). Salween civil networks and residents petition to Administrative Court to help scrap mega Yuam water diversion project. Available from: https://bkktribune.com/salween-civil-networks-and-residents-petition-to-administrative-court-to-help-scrap-mega-yuam-water-diversion-project/

Bangkok Tribune. (2024, January 30). Chiang Mai Administrative Court accepts Yuam water diversion case for deliberation. Available from: https://bkktribune.com/chiang-mai-administrative-court-accepts-yuam-water-diversion-case-for-deliberation/

Bangkok Post. (2025, November 12). Toxic fears prompt testing of river. Available from: https://www.bangkokpost.com/thailand/general/3135521/toxic-fears-prompt-testing-of-river

Ding, L., Tao, J., Tang, B., Sun, J., Ding, C., and He, D. (2023). Anguillids in the upper Nu–Salween River, South-East Asia: species composition, distributions, natal sources and conservation implications. Marine and Freshwater Research, 74(7), 614–624.

Hengsuwan, P. (2019). Not only anti-dam: Simplistic rendering of complex Salween communities in their negotiation for development in Thailand. Knowing the Salween River: Resource politics of a contested transboundary river.

Kimmerer, R. W. (2024). The Serviceberry: Abundance and Reciprocity in the Natural World. Scribner.

Kleinman, A., and Barad, K. (2012). Intra-actions. Mousse Magazine, 34(13), 76–81.

Mohr, A. (2022). Hydraulic Development in the Salween Watershed: The Yuam River Water Diversion Project as a Contested Hydrosocial Territory. Master Thesis, University of Malta.

Sinha, A. K., De, P., Das, A., and Bhakat, S. (2018). Studies on length-weight relationship, condition factors and length-length relationship of Anguilla bengalensis bengalensis, Gray, 1831 (Actinopterygii, Anguillidae) collected from River Mayurakshi, Siuri, Birbhum, West-Bengal, India. International Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Studies, 6, 521–527.

Transborder News. (2025a, November 3). Authorities Ban Contact with Salween River, Fish Consumption After Toxic Arsenic Levels Found. Transborder News. https://transbordernews.in.th/home/?p=44357

Transborder News. (2025b, November 21). Arsenic, Mercury Found Above Safety Limits in Salween; Researchers Suspect Gold Mines. Transborder News. https://transbordernews.in.th/home/?p=44504

Tuck, E. and Yang, K. W. (2012). Decolonization is not a metaphor. Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society, 1(1), 1–40.

Whyte, K. (2020). Indigenous environmental justice: Anti-colonial action through kinship. In Environmental Justice. Routledge, pp. 266–278.

20 / October / 2024

By: Zachary Joseph Czuprynski and Rebecca Marie Serratos

16 / October / 2024

By: Claire Rousell and Brittany Kesselman

5 / July / 2024

By: Nathalia Lizarraga Conchatupa

23 / May / 2022

By: Angie Vanessita