By: Christina Maria Cecilia M. Sayson [1]; Huiying Ng[2]; and Dimas D. Laksmana[3]

17 / February / 2026

The stories told of capital sometimes return larger-than-life, shaping our field of vision and bearing down on our own perceptions with the inexorable weight of its growth imperative. Yet capital is built on its internal contradictions, on the fact that it is composed of the diverse and sometimes directly contradictory commons of local communities and ecosystems, even as it strives to appropriate them.

This visual essay offers a closer look at the relations shaping nature’s transformation into a commodity. By tracing reproductive relations of struggle, death, and resurgence, we underscore how commodity production is contested, enabled, or redirected. A struggle to resist the blasting of the Mekong’s rapids succeeds, drawing potency from river spirits known to inhabit the river; sugarcane in Negros grows each year, pumped with fertilizers and the household labor of farmworkers and their families; a permaculture plot seeks to sow an alternative to industrial agriculture, but draws a partial income stream from its peripheral identity in a tourism hub. This essay reflects on built infrastructure, community-based initiatives, sugarcane plantations, and home gardens, illustrating the varied ways in which reproductive relations shape food-growing landscapes in Thailand, the Philippines, and Indonesia. Commodity production is constantly contested and transformed. The narrative progresses from struggle to death and, finally, to resurgence.

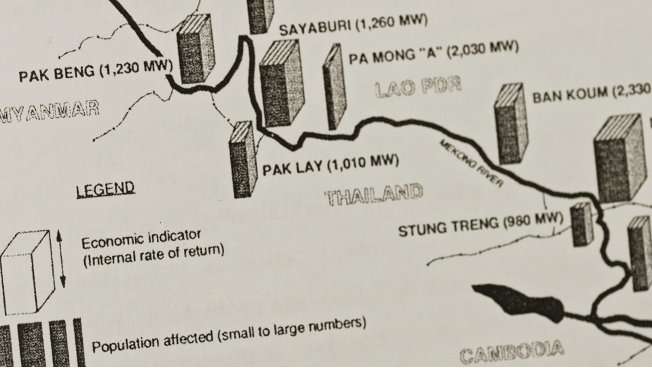

The first section represents how rhythms of flow along the Mekong River are disrupted by the incursions of new infrastructure. Survival may involve the temporary accommodation of new forms of life and infrastructure – but not complete acquiescence. Photos and accompanying text draw on Huiying’s doctoral fieldwork in Thailand between 2021-2025, tracing agroecology’s conditions of possibility. They highlight how villagers and long-time activists work with existing ecologies to reweave knots of socioecological relations. Energies directed towards these reproductive relations of struggle and building maintain bulwarks against imposed changes. What might be seen as NGO or citizen politics used to mobilize local villagers may be seen differently, as a chimerical form of naga, and villagers’ fishing boats expose the juridical violence of a rapids-blasting project agreed upon by the Chinese and Thai state. Rather than naga as a folkloric entity challenging the symbolic order, it is instead a victory via the combined bodies of river, river spirits, and fishers.

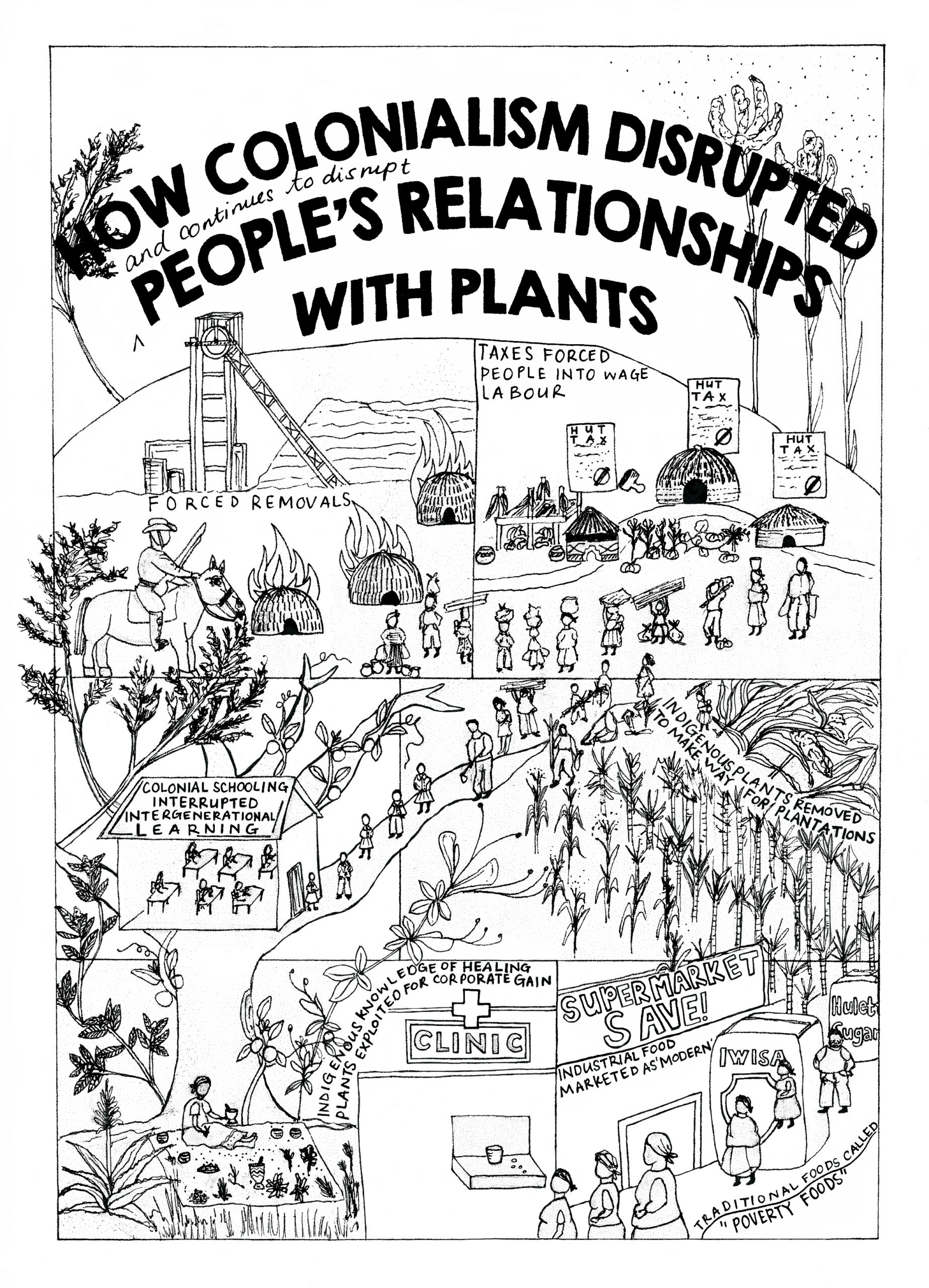

The second section turns to the bleak expanse of an industrial sugarcane plantation on Negros Island in the Philippines, representing death: the subjugation of a landscape to market capitalism. The plantation is a sterile space, where only the cash crop is allowed to grow, and only in the ways that capital demands. In this section, paragraphs that narrate the major elements of Negros societal structure and its economic rhythms are interspersed with photographs and poetry. The paragraphs, photos, and poetry are reflections on Chris’s experience as a member of Negros Occidental’s landholding class. They bring the flattening effect of capitalism’s priorities on the Negros landscape into sharp relief, while the photographs and the poems hint at nuances that dry prose cannot capture. Nuances to the death and sterility of the Negrosanon industrial sugarcane plantation hold the promise of subversion and resurgence in their own right, but they are not foregrounded here.

The final section turns to the promise of resurgence, centering a young couple who cultivate diversity and health through a home garden amid a landscape of capitalist expansion, agribusiness pressures, and land struggles. This story draws on Dimas’ ethnographic study in Yogyakarta to understand the politics of knowledge in organic agriculture. Their practices as landless peasants and active members of a farmer’s market community in Yogyakarta embody a form of “mending damaged nature,” sustaining possibilities for life amid encroachments of capitalist expansion in a rural-urban context. The viability of their livelihoods may be understood as a contradiction of capitalism, in which peripheral goods in a tourist hub generate profits, in expat-frequented spaces facing a long process of gentrification that forces out longtime homeowners. Yet the couple may also be understood as exemplifying a resurgence of reproductive relations through the transmutation of the elements of earth and water they choose to cultivate, by refusing the given world and building one not yet fully comprehensible.

A stretch of the Mekong with a seasonal riverbank garden of vegetables. Blue buckets along the shore hold green mung beans, sprouting. Lao songs float across the river from the opposite bank. A newly-built spirit shrine is set atop a hill, overseeing the river. Author’s images unless noted otherwise, 2022.

This is a story about how a river once flowed seasonally, and how people are reshaping life around its interruption. To patch together a story from disruption, humans often seek to tie together the frayed ends of episodic memory and story. But part of the Mekong’s story is fraying. In its place, something else is emerging, and for you and me to see this space more clearly, we pass on the frayed ends to you.

These riverbanks are a new sight to my eyes. I first came to the riverbank through introductions from friends. A trip organized by Chiang Mai University’s Regional Centre for Social Development provided a chance to visit, and I took off to meet members of the Mekong School, a local organization that works with villages along the river and an extensive network of NGOs and organizations. The Mekong School combines wichaay taibaan (villagers’ participatory action research) with other strategies for action, negotiation, and protest. Over the coming months, I would return several times, never really sure when my next trip would be or what I was looking for yet feeling inexplicably drawn to the river’s many stories.

As the months pass, my irregular rhythms of movement felt awkward and unseasonal, intersecting with the regularity of lives around the river. Humans and birds fish and gather food – fish and river weed amongst them. However, their life patterns change as the river is increasingly boarded up and dammed.

Film still, Holding Rivers, Becoming Mountains, dir. Solveig Qu Suess, 2025.

Yet, some regularity persists. During low tide, green mung beans are sown along the riverbank by hand: first a layer of beans, then a layer of sand, then a layer of beans, and so on. Twice a day, they are given river water. Nearby, on a hill named Pha Than, a spirit house has been built along the slowly transforming waterfront to pay homage to phi nguk, and the lord of Pha Than. A sign for tourists in Thai describes phi nguk, which translates to “mermaid ghosts” or “a large and long aquatic creature,” and notes that drowning incidents were common. The shrine is now part of a sightseeing boardwalk, next to a cycling and running track, made for tourists.

Chinese companies have built check-dams, like this above, along the riverbanks, fixing the riverbank in place.

A stretch of the river’s shore. In the foreground are granite blocks transferred by trucks, former parts of a mountain elsewhere blasted apart for construction, now re-made into a ‘check dam’ to stop up the riverine shoreline.

As dams have been built upstream in China and Laos, the river’s flow has become interrupted and riverbank gardens are less common. As ‘check dams’ are built along the riverbank, the river will be held in, no longer spilling across into the floodplains and bringing nutrient-rich sediment from the Himalayas to the Mekong basin. From the steadiness of the monsoon season comes torrential water releases that are unpredictable and unexpected.

Chinese-built dams in Lao. Film still, Holding Rivers, Becoming Mountains, dir. Solveig Qu Suess, 2025.

For a time, a point of debate was who was at fault for the unpredictable flows: dams or climate change. A new river ecology emerges around recirculated granite and cement. Beneath the loss of a flowing, seasonally changing riverine delta ecology is a heavy layer of cement that arrests the river’s life.

Near the Mekong School, painted cement fish are wrapped around lamp poles. I thought they were wrapped, until one day, Chak, a member of the Mekong School, told me, “They took free-swimming fish from the rivers and stuck them on poles…”. Another time, a tourist van arrived at the Mekong School, and a woman stepped out and asked in Chinese, “Can I buy that special big Mekong fish here?” Pla Beuk, once the size of humans and heavier, are nearly extinct.

Chak watching for birds by night. Film still, Holding Rivers, Becoming Mountains, dir. Solveig Qu Suess, 2025.

The devil catfish, also known as the goonch catfish, belongs to the genus Bagarius. Although these fish look similar, they differ in species, since the genus Bagarius includes several types found in Mae Ngao River.

After every monsoon, during the dry season, the surface of the Mekong is low enough that a weed starts to grow. This weed, or gaay, is harvested by women, who sell it in local markets, dried and pounded. It is a source of nutrition and income. Unexpected water releases from upstream dams are affecting downstream river users’ routines and seasonal ecologies, causing gaay to drop in yield.

Harvesting gaay, river weed. Film still, Holding Rivers, Becoming Mountains, dir. Solveig Qu Suess, 2025.

Gaay need a stable microclimate to grow in: a constant source of sunlight beneath the water’s surface, clear and warm water. The Mekong’s predictable structural stability makes it a holding space that, as Lauren Berlant would put it, organizes the seasonal transformations of an ecological commons. In response to the impact of water releases, in 2009 and 2010, the Rak Chiang Khong Conservation Group sent letters of thanks to the Chinese government, the Thai government, and the UN. These letters, described as gifts by the group [1], did the mediating work of spelling out the discrepancy between each entity’s supposed aims and the reality of social and ecological damage that the dams were unleashing on communities in the Mekong countries – Laos, Thailand, and Vietnam. These letters initiated a series of diplomatic exchanges and realizations of commonality: that the river in question was one and the same: the Mekong River is the Lancang River. Neither the Chinese nor the Thai government had allocated resources for such work, despite their claims to the river as a resource.

The group responded in other ways: bringing a naga to a scouting ship, sent to scout the river ahead of a rapids-blasting project. With villagers from the surrounding villages, the group rallied around the ship and turned it back. It negotiated with Thai and Chinese authorities to halt further rapids-blasting. This was hailed by commentators as successful participatory democracy (Ganjanakhundee 2020). Nonetheless, as upstream dams have been built, sediments now flow at intervals without regard for their ecological structure: upstream dam infrastructure blocks 50% of these sediments, and just-in-time water releases for cargo shipping wash sediment into the water when the water should be low, disrupting the growing conditions for the riverine weed.

It is not just river weed that gets lost in the unstable waters. Drownings have also occurred. These incidents reveal how interpretations of river deaths – and who lives in the river – are changing. One last story serves to illustrate this. In early March, when I was there, a 15-year-old boy was swept down the river. He was employed by a corn farm owner. People had invited them to eat after a day of work, but he and some of the other workers wanted to jump in the river for a quick rinse. This was just 800m downstream from Pak Nam Kham, a meeting point of the tributary and the Mekong. I was introduced to Uncle Nuu, a seasoned hand at the river. He is the person people seek out when someone falls into the river. After he answered my questions, we turned to a related topic.

Pak Nam Kham is known as a place of the naga (phayanak), mermaids (hîa), and the ngûk – a bit like a water buffalo, Luung Nuu said. After a few moments, he continues, saying, ngûk used to take people. If a ngûk wants them, it gets them. Once a person is caught, their skin becomes very slippery. To save them, biting them removes the slippery sheath. From what I can see, Nuu knows the river, and he’s not romantic about it: he describes matter-of-factly how, in 1975, he’d found bombs washed down the river, likely left behind by Chinese soldiers [2]. He’d used these to blast an area the ngûk frequented, to make the place shallower. The ngûk had taken lives, and he wanted to chase the ngûk away. It worked – the ngûk left. For a long time, no one died. But about 5-6 years ago, near-deaths began happening again. Nuu doesn’t know if the ngûk have come back. He thinks the 15-year-old boy who was lost was affected by the higher water levels caused by the dams, not the ngûk. For him, seemingly, there is nothing mysterious or fearful about the water and who it takes – whether spirit or machine propels its currents.

For readers of political economy and material transformation, the ecological world presents a distinct site where secular reason almost needs to be safeguarded from what is otherwise seen as folklore or superstition. It is as if the interpretation of the world as movable or replaceable feels safer precisely because it can be rationally understood and thus rearranged. But Nuu’s reading of the waters seems to me to emphasize impact, not cause or intention, and an ethical orientation that is relational and particular, not absolute or movable. As the ecological dynamics of the Mekong meet new infrastructural forms, place-based understandings of what propels its waters fray into the threads of an unfolding story. If I now pass these threads on to you, do we help to reweave these stories – so that they might be relationally woven into the particular places we are in? In the rhythm of struggle, the knots that have frayed grow clearer. Which brings us to the next essay.

A cane field mid-harvest: the workers have stopped for their midday meal, leaving the field empty to be photographed. Two caros, sugarcane carts meant to be pulled by Philippine water buffalo, rest in the corner, and an electrical tower looms in the middle distance. The fact that this photograph has no human nor animal subjects is deliberate; what is emphasized here is the sterility of the cane field at harvest season, and the relentless and flattening weight of how capital has shaped this scene.

Negros Occidental is known as the “sugar bowl of the Philippines,” and consists of the Western half of Negros Island. It produces up to 65% of the Philippines’ sugar, as of 2023. Sugarcane-growing is the province’s main industry, and Negros society moves to its rhythms. Negros Occidental is notorious for its stark inequalities. The stereotype is as follows: the landholding class, the hacienderos, who own and control capital and hold title to the land, live in decadent grandeur. Meanwhile, the farm laborers and their families, who work the land itself, live in abject poverty. The reality is far more nuanced, but the stereotype endures for a reason. Both the hacienderos and the laborers are tied to the rigid cycles of the crop-year and the stern, spatial delineations of sugarcane plots divided by hectare. Christina, who took the photographs in this section, is a member of Negros Occidental’s landholding class. Like many others in this position, their ancestors arrived from the neighboring island of Panay. Here, they set up haciendas in the southern and eastern parts of the island in the 1800s, and we have lived here ever since.

This section depicts cane fields in different stages of sugarcane production in reverse order – from harvest to planting. The photos here are interspersed with poems I wrote to articulate the complex and subtle ways that resistance and resurgence push back against the killing weight of plantationization and the flattening imperatives of market capital.

Mature cane, ready to harvest, growing by the roadside: a common sight, even within Bacolod City, the capital city of the province of Negros Occidental

The sugarcane industry on Negros Island is highly industrialized, with thirteen fully operational sugar mills, six sugar refineries, and several haciendas still operational and under the control and ownership of old landholding families from Panay. Most of these families are absentee landlords, with little to no connection to the land itself. Green Revolution methods, such as petrochemical fertilizer- and pest control-use, are the norm; they facilitate quick and easy sugarcane production and maximum profits for the families that hold title to the land. Despite the rampant use of industrial methods in Negrosanon sugarcane fields however, working the field itself continues to be done by hand. Landless seasonal migrants often make up the bulk of the sugarcane worker population, particularly during harvest time.

Harvest Season

This time of year,

There is work

Loans are paid off

The city celebrates

With masks and free-flowing drink.

For a price, of course

Still

For now, we can breathe

Even as the calluses deepen on our palms

And the soreness radiates down our legs and backs

But it’s only a matter of weeks

Before the hungry times come again:

There is only so much work

So little compensation

So much expensive, burdensome

Living

Still left to be done.

There is a double alienation at play in both extremes of Negrosanon society. Landholding families only interact with the territories they control through commodification, with the harvest serving as a considerable source of hacienderos’ income for the crop year. On the other end of the spectrum, the landless farm workers and the tenants who live and work on the land cannot connect to it for fear of it being taken away from them at any given time.

In similar fashion, sugarcane, like other numerous other cash crops, are normally grown in a monoculture in Negros Occidental. The sugarcane plants themselves are disconnected from other plants that would have grown in the locality. They are also disconnected from the soil biologies that would have nourished all of these plants as a community. A sugarcane stalk is alienated from its own context, not permitted to interact with other plants. These other plants in question are deemed “weeds,” and are very often summarily dispatched using herbicides like Roundup. The sugarcane is also forcibly separated from local fauna, members of which are deemed “pests” and eliminated with chemical pesticides.

A sugarcane field is only ever allowed to grow sugarcane, not harbor any other forms of life. Sugarcane workers are often forced by poverty and circumstance to dedicate their lives and their bodies exclusively to hacienda-work, even as the seasonality of the sugarcane crop-year creates a lull in the working schedule that usually stretches from June to September. This lull is widely known as Tiempo Muerto: The dead season. The following photo depicts what sugarcane fields may look like at the beginning of Tiempo Muerto.

A ratoon field and the adjacent field being sown to fresh seed cane. Ratooning is a harvesting technique that leaves the sugarcane’s roots intact in the earth so that the plant can be left to regrow. This often results in much lower crop yields and is usually only done if there are no financial resources available for land preparation and planting. During the growing season, no farm work is available, and no harvests can be made, leaving laborers without the resources to survive the next few months

Tiempo Muerto

Land needs to rest,

The old folks warn.

It feeds us

But do we feed it?

Even as the cane grows fat

In the sun

We do not.

Before

The land,

Covered in trees

And all the riotous life

Of living soil,

Needed only time:

Sunlight and typhoons

And the dark, close quiet

Of dying creatures

Rejoining the soil:

The steady, unremarked pulse

Of life and death

Life and death.

In the days before plantations,

We used to take our crops elsewhere,

To let the land feed

On its own rhythm

Life and death, life and death

One feeding the other,

Growing lush in the jungle gloom

And after two years

Maybe seven,

We’d return

To old elsewheres

And reopen them to the sun

With fire and blades,

In rhythms of our own.

But now that we’re to stay put

There is no time

For the earth to catch its breath

No elsewheres left

Still well-fed from life and death,

Life and death

Only the plantation’s insistence

On one kind of life,

One system of exchange

Where fieldworkers

Wait and wait

Hungry as the land.

The land

–forced into unnatural fecundity

With petrochemical fertilizers

Pesticides,

Herbicides,

Death feeding life-

Crying out

Death, death, death.

This photo shows the neat, harrowed rows of a sugarcane field ready to be planted with fresh cane. After harvest, fields are often “disinfected” with fire, even though this is considered illegal under the Philippines’ Clean Air Act (R.A. 8749). Thereafter, fertilizers and, sometimes, sugarcane mill waste (bagasse) are applied in preparation for planting. In this picture, cane tips, or seed cane, have been gathered into clumps in the middle of the field in preparation for planting.

The photos and poetry in this section attempt to make space for both the totalizing weight of capital and the lightness of diversity that allows for local resistance and resurgence. In the things that are and are not within the photograph’s frame and are and are not spoken of in the poems, there are hints of the ways that life, stubborn and endlessly creative life, slips through the cracks of colonial capitalism’s single story. In small, defiant ways, they sever the continuum of that story and reach past its oppressions and ruptures, weaving into the many threads that exist before and beyond the ravening priorities of capital.

“What is this smoothie made of? Do you use blueberries? Why is the color deep purple?” This was a recurring conversation between Mba Septi and her curious local and expat customers at Milas, a local, community-based market in Yogyakarta, where organic producers and consumers meet. Her typical response was “No, we only use local vegetables and fruits. I mix the smoothie with mulberries from mulberry trees that we grow in our garden.” I overheard similar conversations about jamu,or traditional herbal medicine, in a stall next door. This chatter about ingredients and unusual yet affordable concoctions created a festive atmosphere at this farmer’s market south of Yogyakarta. With its long history as a backpackers’ destination and continued over-expansion of the tourism industry, the neighborhood where the farmers’ market is located sits uncomfortably.

The following story and photos of Mba Septi and Mas Budi’s home garden are about how smallness allows for attention to detail, in contrast with the earlier section’s sterile ecosystem and its weight of death. Yet, the internal contradictions of capital imply that weight and lightness hold each other. The couple’s story of how struggle and resurgence are lived within capitalism resonates with Mekong School’s practice of “suu kap sang”: “struggle/fight and build”.

I researched organic agriculture in Yogyakarta in late 2017 and heard a lot about Milas. The space was lively with parents and their children when I arrived, and a couple caught my attention with their mulberry-mixed-with-spinach-and-passion-fruit smoothies. Unlike other booths, which primarily sold meals and processed-healthy products, they sold fresh produce from their low wooden tables and stools.

Over several visits to their home garden, I became more acquainted with Mas Budi and Mba Septi, who introduced themselves as members of the Milas community. Milas serves as a marketing channel for selling the “organic” vegetables from their home garden in Cangkringan, located about 30 kilometers to the north. Located on the slope of Mount Merapi, an active and revered volcano, Cangkringan is home to smallholder farmers and capitalists alike.

I went to Mas Budi’s place to help him build a seed house. I spent the whole day helping him build it. In the evening, we managed to create a structure, though it may have needed another day’s worth of work to finish. I felt the hardship that farmers face, of doing everything on their own and meeting their daily needs. It was a humble life. They were also quite interested in my stories about Europe (Fieldnote January 25, 2018).

Between the spaces that traverse the slopes of Mount Merapi in the north and a community market in the south of Yogyakarta, they struggle to “mend the damaged nature.” Mas Budi shared that they did this by conducting organic agriculture within the currents of capital and the expansion of the organic market. As landless farmers who rent land far from their home villages, he and Mba Septi have developed a distinct farming style, even as farmland in Indonesia continues to shrink.

An unfinished seed house that Mas Budi and Mba Septi built themselves using bamboo and disposed of plastic cover from a nearby bigger organic farm. When I visited them in late 2018, a chicken coop and a goat shelter were added to the home garden. They kept these animals mainly for manure.

Mas Budi was originally from a farming family in Yogyakarta. After marrying Mba Septi from Sumatra, another island in Indonesia, they decided to live independently from their parents by renting farmland owned by a village head in another village. In rural Indonesia, perangkat desa, or village staff, are often paid with land they can rent out to others. On a plot of land a few thousand square meters in size, the couple decided to build a bamboo house and cultivated various plants in the surrounding home garden.

This is the entrance to the home garden. The bamboo structure provides a structure for creepers like passion fruit plants and chayote (Sicyos edulis). During the plants’ growing period, the luscious plants shelter the house where the couple lives from the sweltering heat. This design is influenced by permaculture, which the couple previously learned from other farmers.

In addition to growing common vegetables, like lettuce and swamp spinach (kangkung, Ipomoea aquatica), they also grow local plants that are less commonly known now, like kelor (Moringa oleifera), katuk (Breynia androgyna), kenikir (Cosmos caudatus), and sintrong (Gynura crepidioides). In the farmer’s market, they told me that “foreigners also like them [local vegetables] mas, we introduced that.”

“Wow, actually for salad they are very delicious,” customers said. These plants have different maturation times, and by manually harvesting the leaves, the couple tend to bring different harvests to the farmers’ market. I noticed that customers were attracted to this variety and appreciated it.

In this small plot, they lived off the land by doing organic agriculture. “If somebody has a commitment to farm in an organic way, their lifestyle (gaya hidup) should be organic too,” the couple explained. “We need to understand more about life, about the meaning of health. If you come here, then I serve you unhealthy food, what’s the point? What is the point of doing agriculture if I serve you unhealthy food?” So organic agriculture for them means, “Organic is not only for profit. It should be about healthy life, healthy environment, and healthy mind.”

One principle they practice in agriculture is the recycling of resources. For example, Mas Budi feeds his chickens using scraps from a nearby organic farm, and he gets green waste from a nearby traditional market. He boils these chopped scraps, then mixes them with rice bran. Once it cools, he feeds them to his geese and chickens. The plastic covers for the raised bed are also reused from the organic agribusiness next door. The polybags for planting seedlings are reused many times as well, I learned. This combination of synthetic and non-synthetic resources reflects an uncomfortable set of practical contradictions. Their space sits uncomfortably beside a bigger organic agribusiness that supplies organic produce to supermarkets.

This practice of recycling reflects the contradictions that emerge as the temporalities of agroecological practices meet the homogenized time of industrial practices. In a diverse home garden, the decay and leachate of reused plastic materials interact with the composting and cooking of vegetable scraps, and with varied harvesting times. At the farmer’s markets and within the diverse species nurtured in the garden space, multifaceted relationships are prioritized over the market economy’s needs. It is through working with the contradictions within recycling and the resurgence of noncapitalist logics of relationality between human and more-than-human communities that Mas Budi and Mba Septi create an agroecological space to shelter a meaningful (organic) life amidst the relentless forces of capital expansion.

Agroecology is the cultivation of plural and diverse edible plant varieties in ways that encourage their genetic inter-action within animal-insect-fungal-bacterial-viral webs. It emphasizes the maximization of life’s potential to flourish in its different forms. Each of these three sites holds agroecological relations within capitalist spaces: struggling and contesting the terraforming of space (along the Mekong’s riverbanks), as in Mas Budi and Mba Septi’s home garden and workspace, these contradictions may be simultaneously lived and resisted. The mountain area in Yogyakarta where Mas Budi and Mba Septi are located is worlds apart from the dead ecologies of the haciendas of Negros Occidental, where death has become a totalizing form of control through an embedded intergenerational feudal system born of colonial capitalism. What seems like a new vista of opportunity for some (the Mekong) is, to others, marked by a reductive simplification of a multispecies dance. In the absence of the energy of contradiction, death and dying form a state of putrefaction, with little hope for resurgence. But, thinking with the Mekong School, what galvanizes this energy for contradiction is perhaps simply a longer practice of “suu kap sang”: “struggle/fight and build”.

In this visual essay, we attempted to show rather than tell of temporality and spaces of struggle, death, and resurgence. The seasonalities of the Mekong are interrupted by dam construction, marking the continuation of a struggle to retain cultural and ecological integrity in the face of overwhelming economic and infrastructural pressure. On the other hand, the hacienda’s rigid beat has dictated the tempos of entire populations on Negros Island for well over a century. And finally, the garden ecology of Yogyakarta’s Mas Budi and Mba Septi – affected though it is by capital’s inescapable touch – is an example of the resurgence of a far more fluid temporality that one might call agroecological. It is able to contingently adjust to the multispecies rhythms it pulses with, even in the face of constant pressure to remain economically viable within capitalist hegemony.

In the history of material transformation, capital has sought to “free” the most important asset, land, from earlier relations. In accomplishing that, food-growing spaces and people’s knowledge of cultivation have become alienated from each other. This, in turn, has led to the decay of spaces that had hosted local diverse cultures, ecological knowledges, and foodways. Those of us who perceive this decay, who stand at the crossroads between struggle, death, and resurgence, must find ways to metabolize these energies so that they can be directed towards the rejuvenation of dying spaces and the germination of new, vital spaces, both physical and conceptual.

Bourdieu, P. (1984). Distinction: A social critique of the judgement of taste. Harvard University Press

Ganjanakhundee, S. (2020). Thailand Uses Participatory Diplomacy to Terminate the Joint Clearing of the Mekong with China. PERSPECTIVE, 30, 1-11. https://www.iseas.edu.sg/articles-commentaries/iseas-perspective/2020-30-thailand-uses-participatory-diplomacy-to-terminate-the-joint-clearing-of-the-mekong-with-china-by-supalak-ganjanakhundee/

Chiang Khong Conservation Group. (n.d.) Local cultural ecology and natural resource management in the Mekong Basin: A case study of the Maekhong River-Lanna area. Published by Chiang Khong Conservation Group. Available at the Mekong School’s library.

Gomez, C. (2024, May 21). The Philippine Sugar Industry Amid El Niño: Production Exceeding Projection, Market Dynamics, Import Demands, Export Opportunity, and Raised Health Concerns on “Magic” Sugar. Philippine Council for Agriculture, Aquatic and Natural Resources Research and Development (DOST-PCAARRD). https://ispweb.pcaarrd.dost.gov.ph/the-philippine-sugar-industry-amid-el-nino-production-exceeding-projection-market-dynamics-import-demands-export-opportunity-and-raised-health-concerns-on-magic-sugar/

Johnson, A.A. (2020). Mekong Dreaming: Life and Death along a Changing River. Duke University Press.

Lopez-Gonzaga, V. (1988). The roots of agrarian unrest in Negros, 1850-90. Philippine Studies, 36(2), 151-165. http://www.jstor.org/stable/42633077

Lopez-Gonzaga, V. (1994). Land of Hope, Land of Want: A Socio-Economic History of Negros (1571-1985). Quezon City: Philippine National Historical Society.

National Wages and Productivity Commission. (2024, October 29). Minimum wage increase for private sector and domestic workers in Western Visayas Region approved. Philippine Department of Labor and Employment. https://nwpc.dole.gov.ph/minimum-wage-increase-for-private-sector-and-domestic-workers-in-western-visayas-region-approved/

Sugar Regulatory Administration of the Philippines. (2023). Directory of Sugar Mills. Sugar Regulatory Administration. https://www.sra.gov.ph/view_file/stk_directory_sugar_mills/8kuQeyCrz9vrzmN

Sugar Regulatory Administration of the Philippines. (2023). Directory of Sugar Refineries. Sugar Regulatory Administration. https://www.sra.gov.ph/view_file/stk_directory_sugar_refineries/KO0GNMpuxdrPpCw

[1] Department of Social Sciences College of Arts and Sciences University of St. La Salle Bacolod, Philippines

[2] History, Culture and Communication Studies, Faculty of Humanities, University of Oulu, Finland

[3] Department of Sociology, Faculty of Social and Political Sciences, Universitas Indonesia, Indonesia.

[4] Documented in the book “Local cultural ecology and natural resource management in the Mekong Basin: A case study of the Maekhong river-Lanna area.” Published by Chiang Khong Conservation Group. Available at the Mekong School’s library (physical and digital).

[5] He may have been referring to related groups not necessarily only the Kuomintang.

6 / February / 2026

By: Manapee Khongrakchang

20 / October / 2024

By: Zachary Joseph Czuprynski and Rebecca Marie Serratos

16 / October / 2024

By: Claire Rousell and Brittany Kesselman

5 / July / 2024

By: Nathalia Lizarraga Conchatupa

23 / May / 2022

By: Angie Vanessita