February / 6 / 2025

By: Brittany Kesselman and Sinegugu Zukulu

We argue that an “actually existing alternative” to the industrial food system can be found in the Amadiba community in South Africa. Like other indigenous food systems, Amadiba traditional foodways are underpinned by principles such as interconnection, sacredness, gratitude, abundance and collectivism, rather than growth or profit. The Amadiba community has struggled to protect the land and sea upon which their foodways depend, in the face of attempts by the South African government and international corporations to impose ‘development’ projects. This indigenous food sovereignty struggle highlights the principles-based Amadiba food system as a model for prioritizing social and ecological needs.

indigenous food systems; alternatives to development; land-based livelihoods; food sovereignty; traditional foodways; resistance to mining.

The global industrial food system[1] is increasingly recognized as both contributing to, and vulnerable to, multiple planetary crises, including climate change and other ecological degradation, socio-economic inequality, malnutrition, and rising levels of diet-related diseases (Fanzo et al., 2021; IPES-Food, 2023). The current corporate food regime, characterized by the dominance of transnational food corporations pursuing ever-increasing profits, is failing to meet the nutritional needs of the current world population while also putting those of future generations at risk through its devastating environmental impacts (Clapp, 2023; Gordon et al., 2017; McMichael, 2009).

Small-scale farmers, consumers, environmentalists, social justice advocates and others increasingly call for the transformation of the food system to make it more socially just and ecologically sustainable (Anderson et al., 2021; La Vía Campesina, 2007; Sachs & Patel-Campillo, 2014; Shiva, 2019). These calls align with the kinds of transitions envisaged in degrowth thinking, which is focused on societal (and economic) shifts to prioritize social and ecological well-being rather than economic growth or profit (Escobar, 2015; Roman-Alcalá, 2017). McGreevy et al (2022) have suggested alternative principles that might underpin post-growth food systems, namely, sufficiency, regeneration, distribution, commons and care. These principles resemble many of the underlying principles that inform indigenous food systems around the world and the movements for indigenous food sovereignty that defend and promote these foodways (Huambachano, 2018; Hutchings et al., 2020; Kuhnlein & Receveur, 1996; Morrison, 2011; Radu et al., 2020).

Through the lens of indigenous food sovereignty, and the case of the Amadiba community in Mpondoland,[2] South Africa, this article demonstrates how the community’s traditional foodways—meaning their food production and consumption practices, knowledge, traditions, beliefs and rituals, and how food intersects with their culture and history (Hazareesingh, 2021, pp. 941–942)—represent an ‘actually existing alternative’[3] to the industrial food system. Amadiba traditional foodways are underpinned by principles such as interconnection, sacredness, gratitude, abundance and collectivism, and not by motives of growth or profit. The Amadiba struggle to maintain their autonomy, livelihoods and traditional foodways, and to protect the land, rivers and sea upon which they depend, provides useful lessons for other communities that seek to transition to more just and sustainable food systems.

The concept of indigenous food sovereignty is a useful lens through which to examine the struggles of the Amadiba community to maintain their traditional foodways. The overarching concept of food sovereignty, as defined by the peasant movement La Via Campesina and others in 2007, refers to:

“the right of peoples to healthy and culturally appropriate food produced through ecologically sound and sustainable methods, and their right to define their own food and agriculture systems” (Nyéléni Declaration on Food Sovereignty, 2007).

Indigenous food sovereignty builds on the concept of food sovereignty, with a specific focus on Indigenous peoples’ self-determination as well as their relationships to their lands. It identifies “food sovereignty as an anti-colonial struggle—and a struggle not merely for the levers of capitalist food policy but for the space to imagine social relations differently”(Grey & Patel, 2015, p. 441). The social relations to be reconfigured under indigenous food sovereignty go beyond political sovereignty or even human-to-human power relations, to include Indigenous peoples’ long-standing relations to their land, water, plants, animals and the rest of the more-than-human world around them (Daigle, 2019; Morrison, 2011).

Indigenous foodways look different across different contexts because they are place-based, culturally embedded systems. But the key principles or values that inform these systems seem to be similar across cultures and territories (Kuhnlein et al., 2009). For example, in the case of the Māori people of Aotearoa New Zealand, food is seen as “an embedded connection to human, physical and spiritual realms” (Hutchings et al., 2020). Key values underpinning Māori food systems include interconnectedness, giving back (reciprocity), mutual obligations of guardianship, relationships, cultural standpoint, and self-determination (Hutchings et al., 2020). Similarly, amongst the Quechua people of Peru, food systems are embedded in the philosophy of allin kawsay or living well, with specific values such as reciprocity, collectivity, equilibrium and solidarity applied to traditional food systems (Huambachano, 2018, pp. 9–10). Across cultures, a sense of interconnection to the land and the more-than-human world, responsibility or guardianship, reciprocity, collective organization and spirituality are defining aspects of indigenous food systems, and living on the land in line with these values is a crucial aspect of indigenous food sovereignty (Hazareesingh, 2021; Morrison, 2011; Radu et al., 2020; Whyte, 2016).

In light of South Africa’s long and violent history of settler colonialism, the notion of coloniality is also useful in thinking about the disruption of traditional Amadiba foodways. Coloniality “refers to long-standing patterns of power that emerged as a result of colonialism, but that define culture, labor, intersubjective relations, and knowledge production well beyond the strict limits of colonial administrations” (Maldonado-Torres, 2007). From the establishment in 1652 of the Dutch East India Company (VOC) fort and gardens at the Cape, European settlers expanded north and east into the rest of what is now South Africa over the next 250 years, seizing land and imposing their authority through violence as well as the ‘civilizing mission’ of the Christian missionaries (Alberti, 1968; MacKenzie, 2008; Majeke, 1952; Moffat, n.d.; Tisani, 1992). Technically, with the fall of the racist apartheid regime and the transition to democracy in 1994, South Africa is no longer a settler colony. Yet despite the rights-based constitution and democratic majority rule, the prevailing power relations, systems of knowledge and economy in South Africa continue to reflect those put in place under settler colonialism (Ndlovu-Gatsheni, 2015).

Settler colonialism had devastating impacts on the foodways of the Indigenous peoples[4] of South Africa (Kesselman, 2023). The ongoing coloniality of South Africa’s food system can be seen in its racialized, unequal distribution of land, large-scale monoculture production, manufacturing of unhealthy ultra-processed foods, and concentration of value and profit in the hands of a few powerful corporations (Greenberg, 2016; Kroll, 2017; Pereira, 2014). Yet traditional foodways based on different foods, practices and principles are still in existence in some parts of the country, and these provide a model of more socially just, ecologically sustainable food systems.

This article draws on the first author’s semi-structured interviews with forty traditional knowledge holders, predominantly elders, in seven villages[5] in the territory of Amadiba, in late 2021. Participants were selected for their knowledge, with assistance from the second author and local farmer groups. The interviews are complemented by and triangulated against the second author’s extensive knowledge of the history, ecology, customs and current struggles of Amadiba, which he has garnered as a long-time resident of the area, program manager of the local non-governmental organization Sustaining the Wild Coast (SWC) for four years, and deputy chair of the SWC board for 16 years. The article also draws on conversations between the two authors and with other members of SWC. Additional information from historical sources and academic literature helps to contextualize the research and is triangulated with the interviews and personal knowledge to avoid bias.

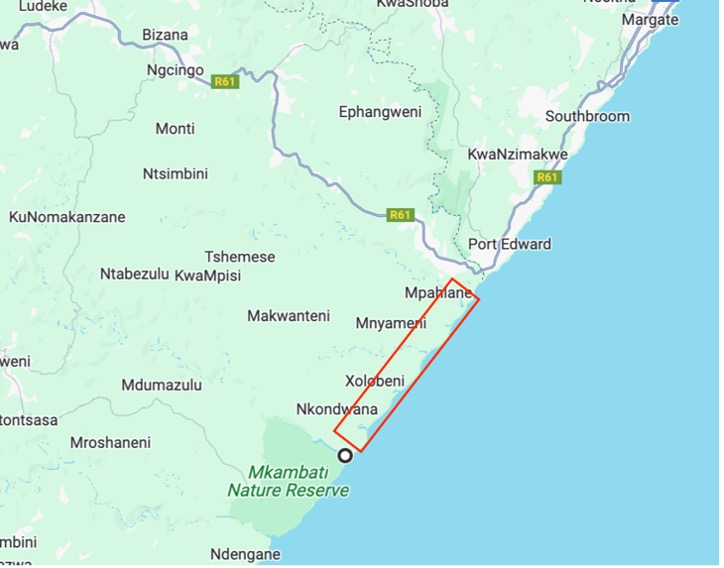

The community of Amadiba is located in Mpondoland on the Wild Coast, in the Eastern Cape province of South Africa (see figure 1). It is located in the Winnie Madikizela-Mandela local municipality (formerly known as Mbizana), which had an unemployment rate of 44% in the 2011 census and was the seventh poorest municipality in the country in 2016 (Maluleke, n.d.; Winnie Madikizela Mandela Local Municipality, 2022). The Maputaland-Pondoland-Albany biodiversity hotspot, where Amadiba is located, is the second most biodiverse floristic region in southern Africa. The coast of Mpondoland also contains a marine protected area and several critical marine habitats (Conservation International Southern African Hotspots Programme & South African National Biodiversity Institute, 2010). The Amadiba region has very good soil and rain for agriculture. In light of the favorable agricultural conditions and rich natural biodiversity, it is not surprising that many residents of Amadiba depend heavily on land and marine resources for their food and livelihoods (Bennie, 2011, 2023; Koen, 2016; Zamchiya, 2019).

Mpondoland was one of the last independent kingdoms to be annexed to then British-ruled South Africa, in 1894. It was also one of the last areas where taxes were imposed and, even before that, missionaries only arrived in the area in 1828 (Beinart, 2014, p. 389; Hunter, 1979, pp. 7, 349). The remoteness of the area, its poor infrastructure and the relative rarity of European traders mean that Mpondoland has a shorter history of contact with colonialism than most other parts of South Africa. The Mpondo people successfully resisted being removed from their land and retained their traditional governance system.

The traditional Mpondo governance system revolves around the Komkhulu or traditional court. As Zukulu (2012, p. 41) explains, there are multiple levels of Komkhulu from the local level (where a sub-headman or sub-headwoman, usibonda, presides), through the headman or headwoman (inkosana), the chief (inkosi), and finally the king or queen (Kumkani or Kumkanikazi) for the whole Mpondo nation. “All issues that affect the community within the area of jurisdiction of the Komkhulu must be discussed at the Komkhulu when it meets” (Zukulu, 2012, p. 41). The Komkhulu is the site of the imbuzo, a gathering for community decision-making in which any community member may participate and ask questions. This process of participatory, democratic decision-making gives the outcomes legitimacy and also contributes to accountability through council members (Zukulu, 2012, p. 43). It illustrates how levels of nested, relational sovereignty can operate (Iles & de Wit, 2014; Iles & Montenegro, 2013)

The people of Mpondoland have a strong tradition of resistance to loss of autonomy and threats to their land-based livelihoods through the imposition of development projects by the colonial/apartheid state and/or private capital. The most famous instance was the Mpondo Rebellion[6] of the 1950s to early 1960s (see Kepe & Ntsebeza, 2011; Mbeki, 1964). The Rebellion rejected the apartheid government’s “Betterment” schemes, which sought to forcibly remove people from their homesteads and relocate them into more densely settled villages, separating residential, agricultural and grazing areas that had previously been intermingled under traditional Mpondo settlement patterns. The amaMpondo correctly saw that this disruption would have a negative impact on their lives and livelihoods (Beinart, 1992; de Wet & McAllister, 1983). The Mpondo Rebellion also rejected the Bantu Authorities Act, through which apartheid South Africa expanded and co-opted the authority of traditional leaders to impose policies, contrary to the Mpondo custom of participatory, consensus-based local decision-making (De Wet, 2013; Zukulu, 2012). The people’s resistance was met with violence from security forces[7] (De Wet, 2013; Kepe & Ntsebeza, 2011). Despite the heavy cost, the Mpondo Rebellion was successful in resisting relocation.

Since the early 2000s, most of the Amadiba community has resisted titanium mining on a stretch of coastal sands (see figure 2) (Bennie, 2023; De Wet, 2013; Healy, 2022). Mining opponents argue that the mine would displace households, pollute agricultural and grazing lands and water, disrupt community life and cut off people’s relationships with ancestral graves and sacred sites that are critical to their spiritual and cultural life (Mbuthuma, 2022; Zukulu, 2012). The resistance, through the Amadiba Crisis Committee (ACC), has entailed a combined strategy of legal challenges, physical obstruction of mining-related activities, media engagement to raise public awareness and mobilize public support, and promotion of an alternative vision of development. So far, the Amadiba community has successfully defended their right to say no to mining (Bennie, 2020; Clarke, 2014; De Wet, 2013; Healy, 2022; Mbuthuma, 2022; Zukulu, 2022). The community has also resisted construction of a new toll highway through the area, which would have similar negative social and environmental effects and is perceived as designed to support the proposed mine (Healy, 2022; Zukulu, 2012).

In 2021, the community mobilized yet again to resist the imposition of extractive development, as the oil company Shell announced it would conduct offshore seismic surveys to explore potential oil and gas reserves along the Wild Coast. Again, combining legal strategies with public protests (see Figure 3), the Amadiba community and others successfully argued that there had been insufficient public consultation and that the blasting could damage marine life, fishing livelihoods, and cultural and spiritual practices linked to the sea (Mahlatsi & Mudau, 2023; Tomaselli & de Wet, 2023). This resulted in Shell’s Exploration Rights being set aside (Sustaining the Wild Coast NPC and others v Minister of Mineral Resources and Energy and others (3491/2021) ZAECMKHC, 2022).

Amid the Amadiba community’s recent resistance to mining and the toll road, community members met and developed the “Mgungundlovu Community Development Statement”, which offers four principles that should inform development:

This statement reflects the principles and values that underpin Amadiba traditional foodways (as we illustrate below). The statement, and the democratic participatory process by which it was developed, serve as a model for how indigenous food sovereignty operates in practice, in the Amadiba community and beyond.

This section provides a brief overview of traditional Amadiba foods, food practices, knowledge transmission and the principles or values that sustain them.

Traditional foods

The traditional diet in the Amadiba community was very diverse, with a mix of farmed and wild-harvested foods from land and sea. The staple grains were sorghum and (from the 16th century), maize. A wide range of legumes (beans and peanuts), squashes (pumpkins and calabash), root crops (amadumbe or taro root and sweet potatoes) and melons also formed part of the diet. The Mpondo people kept cattle for milk (consumed as fermented dairy, known as amasi) and occasionally meat. Other livestock such as goats, pigs and chickens also supplied meat. In addition to farmed foods, the traditional Mpondo diet relied significantly on wild-harvested foods, including wild greens (collectively referred to as imifino), fruits, hunted game and many types of seafood (oysters, mussels, crayfish, limpets, etc.). Many of the wild greens also had medicinal uses.

Our research found that while many farmers in the Amadiba community have adopted non-traditional vegetables and fruits (such as tomatoes, onions, cabbage, spinach, peach and guava), their focus remains on traditional crops such as maize, pumpkin, amadumbe (taro) and beans. Sorghum, an indigenous grain, has been almost completely abandoned in favor of maize, with most participants blaming the problem of birds eating the crop. Wild greens, fruits, and seafoods are still consumed by many households, although honey collection and hunting are mentioned less frequently.

Traditional farming practices

Traditional Mpondo agriculture centered around the homestead (see Figure 4).[8] Communal land was allocated to individual families for use by the local sub-headman (on behalf of the community) in a process that involved consensus among all the neighbors. There were gardens at the homestead, as well as fields slightly further away (Shackleton & Hebinck, 2018). Livestock were pastured on communal grazing land. Women were mostly responsible for tending household gardens, while men helped with ploughing, tending cattle, and working in the fields. Children assisted their families. Traditional planting methods remembered by participants included hand-scattering seeds, planting multiple crops together (companion planting), saving seeds and using cattle manure for soil fertility. The good climate and healthy soils allowed year-round planting.

While most of the above remains the same today, there has been some “modernization” of planting practices in the area, with some households adopting monoculture, planting in straight rows, tractor use, store-bought seed, chemical fertilizer and pesticides. Others have received training from NGOs in agroecological production methods, which are closer to the traditional methods. Amongst the research participants, most still practiced at least some traditional methods.

Food knowledge transmission

As in most indigenous cultures, knowledge of traditional food practices was passed down from one generation to the next through observation, stories and experiential learning (Alanamu et al., 2018; Ferguson et al., 2022; Hazareesingh, 2023). Children learned by working in the fields with their elders or joining them to gather wild foods (Dold & Cocks, 2012). Every elder who participated in this research learned to farm from their parents and/or grandparents and passed on the knowledge to their children. One said, “When I was young my parents were the ones farming, and I would follow them and see how to farm” (participant 1). A young herbalist expressed his gratitude for his grandfather’s teaching saying, “something very important in our community is our indigenous education. You must know how to plough, how to cook, how to look after cattle, how to use dogs, how to ride horses. That is our first education. They [elders] know everything about that” (participant 4).

Yet, the chain of knowledge transmission can be easily interrupted. One participant lamented the role of mobile phones and television, asking, “How can I narrate a story to a child who is busy watching a movie on a screen?” (participant 11). In addition to the distraction, access to these devices exposes children to targeted advertising for processed foods (Lewis et al., 2020; Yamoah et al., 2021). Elders expressed frustration at young people’s lack of interest in learning to farm traditional crops and prepare traditional dishes. One said, “They can’t learn because all they want is Western things, every day you have to remind them to go to the garden” (participant 17).

Some community members, working with Sustaining the Wild Coast (SWC), have sought to rekindle the interest of young people in traditional foodways using innovative methods such as organizing a food festival to showcase traditional foods. A member of the traditional council said of the festival, “this thing must happen every year so that it will bring back our children to see what was happening before” (participant 12). Another NGO trained young people in participatory video work, to document traditional foods and food practices.

Principles underpinning traditional Amadiba foodways

The first principle underpinning traditional Amadiba foodways was interconnection and interdependence with nature, as opposed to the Cartesian dualism that sees humans as separate from nature (Grosfoguel, 2007; Simpson, 2017). In Mpondoland, people understand that they are connected to, and dependent upon, the land and water for food and medicines as well as their ongoing relationship with their ancestors. “We have a holistic, relational worldview that recognizes the interdependence of all members of the community and also our dependence on the natural world within which we live” (Zukulu, 2012, p. 30). Many respondents indicated this close relationship with the land:

“The land is our life” (participant 1).

“Land is food to us, land is life to us, we don’t need jobs” (participant 20).

Participants also expressed their connection to the water—both rivers and the sea—as another source of food and medicines. One traditional healer indicated, “It is said that the river should be treated well because there are things that we take out of the rivers … that is why I clean the rivers” (participant 9).

The connection extends to other animals as well. As one farmer explained, “There are small crows, if you insult them, they will come and eat a lot in your garden … Once you apologize to them, they will look at you and go and leave your crops” (participant 3). This kind of relationship to a potential pest is quite different from the mainstream agricultural approach of exterminating anything that might reduce crop yield. Customary laws reflect this notion of interdependence. For example, no one is allowed to chop down or kill a wild fruit tree, because they provide food to travelers, birds and other wildlife.

A second principle of traditional Amadiba foodways was sacredness. The natural world was, and still is, a site of connection to the ancestors, who play an important role in people’s lives in terms of health, good or bad fortune, and marking important life events, as well as being intermediaries to higher powers who influence the rains and the harvest (Canham, 2023; Ngubane, 1977; Zukulu, 2012). The sacred aspects of the relationship to the landscape were described as follows:

“It is an animate landscape within which our culture developed and which we share not only with wild plants and animals but also with spirits and other beings. We regard ourselves not as being separate from the land, but as members of a community which has very specific obligations to respect not only our ancestors but also the spiritual dimensions of the landscape within which we live” (Zukulu, 2012, pp. 32–33).

The relationship to the earth as a site of ancestral connection begins from birth, when the umbilical cord is buried in the soil, and extends to death, when a deceased elder is buried with seeds so that once he or she crosses over to become an ancestor, he or she will be able to bring abundance to the family left behind. There are many sacred sites, such as hills where people traditionally went to pray for rain during a drought, as well as the rivers and the sea where ancestral spirits reside (Canham, 2023; Sustaining the Wild Coast NPC and others v Minister of Mineral Resources and Energy and others (3491/2021) ZAECMKHC, 2022). Many respondents remembered their parents participating in rituals and going to the mountain to pray for rain and make offerings of traditional beer (participant 6; participant 8). One woman recalled these ancestral prayers, “now when the elders come back [from the mountain], let the ancestors have a drink, or a goat, to thank them” (participant 3). Community members still participate in some rituals, but they are not as frequent as in the past.

Gratitude for abundance was another important principle of traditional Amadiba foodways. Expressions of gratitude, in the form of brewing traditional beer, underpinned celebrations of the harvest (participant 2). These celebrations were known as “resting (or cooling) the feet of the oxen,” (ukucika amanqina eenkabi) because the oxen worked hard to plough the fields and then transport the harvest to the homesteads on wooden sledges. At harvest-time, “traditional beer is brewed, samp (stamped maize) is ground and cooked, fermented porridge is also prepared, and people would feast” (participant 1). This celebration has declined but has not disappeared.

Another key principle was collectivism or sharing. When any individual needed additional help, they organized a collective work party known as ilima (Hunter, 1979; McAllister, 2005). The neighbors came to assist in a spirit of friendship and reciprocity and were served traditional beer as a sign of thanks. Every participant remembered ilima from their childhood. One recalled, “Yes, this is the thing that was used a lot for ploughing. For example, if I ploughed a big garden, it would overwhelm me. I would call people, and they would plough or weed it for me” (participant 12). During collective work in the fields or while threshing the grains after harvest, people would sing together (participant 5).

Another collective practice was the work company (inkampani), in which a group of homesteads came together to plough. If some members of the group did not have cattle, they contributed their labor. This practice ensured that all households, even those without cattle, were able to plough their land. The spirit of helping one’s neighbor extended beyond ilima and inkampani. One participant recalled that “people would come and assist you without being asked if they saw that you are overwhelmed by weeds in your garden” (participant 17), a practice called ukuthatha. People also shared and exchanged seeds (participant 6; participant 17) and even food. As one participant recalled, “we grew food, we did not sell, and we gave some to our neighbors” (participant 10). Participants indicated that these collective work practices still happen, but less frequently because nowadays, people want to be paid for their labor.

A very important principle of traditional Amadiba foodways was self-sufficiency or local autonomy. Mpondo households grew and gathered enough food to sustain themselves, and traditional methods of food preservation (e.g., drying wild greens or storing grains in underground pits) ensured they did not go hungry in case of drought. Today, growing their own food gives Mpondo households a degree of independence from the cash economy and insulation from price shocks and other crises, such as the COVID-19 lockdowns (Koen, 2016; Zamchiya, 2019). Many participants highlighted this independence. One explained, “the thing I love about farming is that I can cook without going to the shop … without spending money, I feed my children” (participant 12). Another said, “without farming, there is no life” (participant 20). Wild food resources from the commons—greens (imifino), fruits, seafood and occasionally game—also contribute to food sovereignty and autonomy.

The Amadiba’s deep knowledge of natural cycles allowed them to benefit from the abundance of the land and sea throughout the year. The agricultural calendar was traditionally organized around natural signals. For example, the return of the migratory uphezukomkhono bird (red-chested cuckoo or Cuculus solitarius) or the flowering of the umsintsi (coral tree or Erythrina lysistemon) in September indicated the time to start planting. The names of months refer to agricultural and natural cycles. March is EyoKwindla, the time when there is plenty of green food, and April is uTshazimpuzi, the time of the withering pumpkin leaves when the cold weather begins.

For every season there were different crops and wild foods to eat. One elder explained how she continued to enjoy a very diverse diet because of her farming skills and knowledge of wild greens:

“I would pick imifino (wild greens) for isigwampa (maize porridge with greens) … Just to change the menu I would cook madumbes (taro root), as the seasons are changing sweet potatoes and madumbes will change their texture … then I pick blackjack (a wild leafy green). … because it is winter, we would then pick uzikeyi (in the dandelion family), there is another one called indlabulele, irhwaba (dandelion or sow thistle) I would then mix everything and cook green porridge” (participant 13).

In their resistance to imposed development, the Amadiba community has insisted that they are not poor (Koen, 2016; Zukulu, 2012). One young participant stated emphatically that “people are not hungry, they are full in their belly and they have got everything in their house” (participant 20). This is due to the natural abundance of the land, the skills and knowledge of the local people, as well as the principles that underpin traditional Amadiba foodways—all of which ensure that the community has a “sufficient, healthy and nutritionally varied diet” (Koen, 2016, p. 8). Many other communities in South Africa with similar or higher levels of income have lower levels of food security.

Participants in this research project lamented the loss of many traditional foods and food practices from their childhoods, including a decline in ilima, less sharing of food and an increasing preference among young people for purchased food such as rice. A typical view was that “money ruined everything” (participant 5), and that the youth “don’t want to work the soil … they have stopped eating [traditional foods] because now they have money” (participant 13).

The perception that traditional foodways are being lost must be balanced against the fact that indigenous foodways are not static. Food knowledge is embodied, living knowledge, which adapts to changing circumstances. Monica Hunter observed efforts by the state to “modernize” agriculture in Mpondoland in the early 1930s, involving ploughing, planting monocultures in rows, as well as bringing in fertilizer (Hunter, 1979, p. 94). Similarly, Christian and school-educated people were discouraged from participating in traditional rituals or harvest celebrations (Hunter, 1979, pp. 91, 174, 268, 351). The changes in foodways discussed in this article have been underway for more than a century.

However, with each generation, more traditional knowledge is abandoned and lost. Mpondo households do seem more deeply enmeshed in the capitalist economy and global food systems than in the past, based on interviews with elders and a comparison to research from about 90 years ago (Hunter, 1979). The introduction of social grants after 1994 enabled many more households to purchase food (Koen, 2016; Zamchiya, 2019), either from neighboring towns or from corporate food retailers who set up mobile shops at the grant payment point each month.

It is useful to distinguish between externally imposed changes (due to colonialism, capitalism, or imposed development) and internally driven changes, grounded in local principles. Efforts by SWC and others to revive indigenous knowledge, through food festivals and participatory video, may stimulate young people’s interest, strengthen inter-generational food knowledge transmission and promote food sovereignty.

This article has provided an overview of Amadiba traditional foodways, as well as the struggles that have enabled the Amadiba community to retain these foodways in the face of colonial/apartheid repression and attempts to impose extractivist development. The principles underpinning traditional Amadiba foodways that emerged in this research—interconnection, sacredness, gratitude, collectivism, self-sufficiency and an understanding of natural cycles—are aligned to many other indigenous food systems. The Amadiba’s struggles to defend their autonomy, participatory governance, and the land and water on which they depend, are struggles for indigenous food sovereignty (Bennie, 2023; Roman-Alcalá, 2017).

At present, it is not possible for the Amadiba community to have a food system completely outside of the global, industrial food system. Despite the relative remoteness of Mpondoland, it is still embedded in South African and global food systems, and the broader capitalist economy. Neither can the clock be turned back to before contact with colonialism and capitalism. However, the extent to which the Amadiba community has managed to resist imposed development and retain land-based livelihoods and traditional foodways may provide lessons for other communities seeking post-growth food systems. By grounding their struggles in indigenous principles and participatory democratic governance (Komkhulu), the Amadiba community has been able to maintain their traditional foodways and their land-based local autonomy.

This work is based on the first author’s research, supported by the National Research Foundation of South Africa (Grant Number: 129571). The first author would like to acknowledge the assistance of Sustaining the Wild Coast (SWC) in organizing fieldwork, the excellent interpretation and guidance of Lindelani Gama Mbulawa in the field, and the transcription assistance of Ntombomzi Nkwentsha. The second author, Sinegugu Zukulu, was co-winner of the Goldman Environmental Prize for Africa in 2024 for his role in stopping destructive seismic testing for oil and gas off South Africa’s Wild Coast. See: https://www.goldmanprize.org/recipient/sinegugu-zukulu-nonhle-mbuthuma/. The authors would like to thank the two anonymous reviewers for their useful comments.

African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights. (2007). Advisory Opinion of the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights on the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

Alanamu, T., Carton, B., & Lawrance, B. (2018). Colonialism and African Childhood. In M. Shanguhyia & T. Falola (Eds.), The Palgrave Handbook of African Colonial and Postcolonial History (pp. 389–412). Palgrave Macmillan.

Alberti, L. (1968). Account of the Tribal Life and Customs of the Xhosa in 1807. A.A. Balkema.

Anderson, C. R., Bruil, J., Chappell, M. J., Kiss, C., & Pimbert, M. P. (2021). Agroecology now! Transformations towards more just and sustainable food systems. Palgrave Macmillan Cham. https://doi.org/10.1080/21683565.2021.1952363.

Beinart, W. (1992). Transkeian smallholders and agrarian reform. Journal of Contemporary African Studies, 11(2), 178–199. https://doi.org/10.1080/02589009208729537.

Beinart, W. (2014). A century of migrancy from Mpondoland. African Studies, 73(3), 387–409. https://doi.org/10.1080/00020184.2014.962869.

Bennie, A. (2011). Questions for labour on land, livelihoods and jobs: A case study of the proposed mining at Xolobeni, Wild Coast. South African Review of Sociology, 42(3), 41–59. https://doi.org/10.1080/21528586.2011.621234.

Bennie, A. (2020). Defending the commons: The case of the Amadiba victory on the ‘Right to Say No.’ In F. Guilengue (Ed.), Action Matters: Six success stories of struggles for commons in Africa. Rosa Luxemburg Stiftung.

Bennie, A. (2023). Food sovereignty and the agrarian question in South Africa: Class dynamics and collective agency from below. University of the Witwatersrand.

Canham, H. (2023). Riotous Deathscapes. Wits University Press.

Clapp, J. (2023). Concentration and crises: Exploring the deep roots of vulnerability in the global industrial food system. Journal of Peasant Studies, 50(1), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2022.2129013.

Clarke, J. G. I. (2014). amaDiba moment: How civil courage confronted state and corporate collusion. In G. Khadiagala, P. Naidoo, D. Pillay, & R. Southall (Eds.), New South African Review 4: A fragile democracy – Twenty years on (pp. 142–155). Wits University Press.

Conservation International Southern African Hotspots Programme, & South African National Biodiversity Institute. (2010). Ecosystem Profile Maputaland-Pondoland-Albany Biodiversity Hotspot. Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund.

Daigle, M. (2019). Tracing the terrain of Indigenous food sovereignties. Journal of Peasant Studies, 46(2), 297–315. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2017.1324423.

de Wet, C., & McAllister, P. (1983). Rural communities in transition: A study of the socio-economic and agricultural implications of agricultural betterment and development (Development). Rhodes University Institute of Social and Economic Research.

De Wet, J. (2013). Collective agency and resistance to imposed development in rural South Africa. In Working Papers in Sociology (Vol. 373). Universität Bielefeld.

Dold, T., & Cocks, M. (2012). Voices from the Forest: Celebrating nature and culture in Xhosaland. Jacana.

Eriksen, S. (2013). Defining local food: Constructing a new taxonomy—Three domains of proximity. Acta Agriculturae Scandinavica, Section B—Soil and Plant Science, 63(Supp 1), 47–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/09064710.2013.789123

Escobar, A. (2015). Degrowth, postdevelopment, and transitions: A preliminary conversation. Sustainability Science, 10(3), 451–462. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-015-0297-5.

Fanzo, J., Bellows, A. L., Spiker, M. L., Thorne-Lyman, A. L., & Bloem, M. W. (2021). The importance of food systems and the environment for nutrition. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 113(1), 7–16. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/nqaa313.

Ferguson, C. E., Marie Green, K., & Switzer Swanson, S. (2022). Indigenous food sovereignty is constrained by “time imperialism.” Geoforum, 133(May), 20–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2022.05.003.

Gordon, L. J., Bignet, V., Crona, B., Henriksson, P. J. G., Van Holt, T., Jonell, M., Lindahl, T., Troell, M., Barthel, S., Deutsch, L., Folke, C., Haider, L. J., Rockström, J., & Queiroz, C. (2017). Rewiring food systems to enhance human health and biosphere stewardship. Environmental Research Letters, 12(10). https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/aa81dc.

Greenberg, S. (2016). Corporate Power in the Agro-food System and South Africa’s Consumer Food Environment. Institute for Poverty, Land and Agrarian Studies (PLAAS), University of the Western Cape.

Grey, S., & Patel, R. (2015). Food sovereignty as decolonization: Some contributions from Indigenous movements to food system and development politics. Agriculture and Human Values, 32, 431–444. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-014-9548-9

Grosfoguel, R. (2007). The epistemic decolonial turn. Cultural Studies, 21(2–3), 211–223. https://doi.org/10.1080/09502380601162514.

Hazareesingh, S. (2021). “Our Grandmother Used to Sing Whilst Weeding”: Oral histories, millet food culture, and farming rituals among women smallholders in Ramanagara district, Karnataka. Modern Asian Studies, 55(3), 938–972. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0026749X20000190.

Hazareesingh, S. (2023). Food heritage for sustainable futures: Women’s cultures and knowledge as hidden pillars of alternative foodways. In C. Cross & J. Giblin (Eds.), Critical Approaches to Heritage for Development. Routledge.

Healy, H. (2022). Struggle for the sands of Xolobeni – From post-colonial environmental injustice to crisis of democracy. Geoforum, 133(May), 128–139. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2022.05.002.

Huambachano, M. (2018). Enacting food sovereignty in Aotearoa New Zealand and Peru: Revitalizing Indigenous knowledge, food practices and ecological philosophies. Agroecology and Sustainable Food Systems, 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/21683565.2018.1468380.

Hunter, M. (1979). Reaction to Conquest. David Philip Publishers.

Hutchings, J., Smith, J., Taura, Y., Harmsworth, G., & Awatere, S. (2020). Storying Kaitiakitanga: Exploring Kaupapa Mäori land and water food stories. MAI Journal, 9(3), 183–194.

Iles, A., & de Wit, M. (2015). Sovereignty at What Scale? An Inquiry into Multiple Dimensions of Food Sovereignty. Globalizations, 12(4), 481–497. https://doi.org/10.1080/14747731.2014.957587

Iles, A., & Montenegro, M. (2013). Building Relational Food Sovereignty Across Scales: An Example from the Peruvian Andes. Food Sovereignty: A Critical Dialogue.

IPES-Food. (2023). Breaking the cycle of unsustainable food systems, hunger and debt.

Kepe, T., & Ntsebeza, L. (Eds.). (2011). Rural Resistance in South Africa: The Mpondo Revolts after fifty years. Brill.

Kesselman, B. (2023). Transforming South Africa’s unjust food system: An argument for decolonization. Food, Culture and Society, 00(00), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/15528014.2023.2175483.

Koen, M. (2016). Xolobeni: Socio economic analysis and research overview. MK2, Supporting Affidavit in the matter between Duduzile Baleni (First Applicant) and 128 others and Minister – Department of Mineral Resources (First Respondent) and six others in the High Court of South Africa (North Gauteng, Pretoria)

Kroll, F. (2017). Foodways of the Poor in South Africa: How Poor People Get Food, What They Eat, and How This Shapes Our Food System. PLAAS.

Kuhnlein, H. V., Erasmus, B., & Spigelski, D. (Eds.). (2009). Indigenous Peoples’ food systems: The many dimensions of culture, diversity and environment for nutrition and health. UN FAO.

Kuhnlein, H. V., & Receveur, O. (1996). Dietary Change and Traditional Food Systems of Indigenous Peoples. Annual Review of Nutrition, 16, 417–442. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.nutr.16.1.417.

La Vía Campesina. (2007). Nyéléni Synthesis Report.

Lewis, D., Bhoola, S., & Mafofo, L. (2020). Corporate fast-food advertising targeting children in South Africa. In J. May, C. Witten, & L. Lake (Eds.), South African Child Gauge: Food and nutrition security (pp. 62–71). Children’s Institute.

MacKenzie, J. (2008). ‘Making Black Scotsmen and Scotswomen?’ Scottish missionaries and the Eastern Cape Colony in the nineteenth century. In Empires of Religion (pp. 113–136). Palgrave Macmillan.

Mahlatsi, M. L. S., & Mudau, J. (2023). State and business collaboration in the neoliberalisation of nature: An analysis of mining bids on the Wild Coast, South Africa. African Journal of Development Studies, si1, 145–165.

Majeke, N. (1952). The role of the missionaries in conquest. Society of Young Africa.

Maldonado-Torres, N. (2007). On the coloniality of being. Cultural Studies, 21(2–3), 240–270.

Maluleke, R. (n.d.). A Poverty Mapping of the Poorest Provinces, Metros, Districts and Localities in South Africa. Statistics South Africa.

Mbeki, G. (1964). South Africa: The peasants’ revolt. Penguin Books.

Mbuthuma, N. (2022). Resisting Extractivist Development. New Agenda : South African Journal of Social and Economic Policy, 83, 90–94.

McAllister, P. (2005). Xhosa cooperative agricultural work groups: Economic hindrance or development opportunity? Social Dynamics, 31(1), 208–234. https://doi.org/10.1080/02533950508628702.

Mcgreevy, S. R., Rupprecht, C. D. D., Niles, D., Wiek, A., Carolan, M., Kallis, G., Kantamaturapoj, K., & Mangnus, A. (2022). Sustainable agrifood systems for a post-growth world. Nature Sustainability. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-022-00933-5.

McMichael, P. (2009). A food regime genealogy. Journal of Peasant Studies, 36(1), 139–169.

Moffat, R. (n.d.). Missionary Labours and Scenes in Southern Africa. Cambridge University Press.

Morrison, D. (2011). Indigenous food sovereignty: A model for social learning. In C. H. Wittman, A. A. Desmarais, & N. Wiebe (Eds.), Food sovereignty in Canada: Creating just and sustainable food systems (pp. 97–113). Fernwood Publishing.

Ndlovu-Gatsheni, S. (2015). Decoloniality in Africa: A continuing search for a new world order. Australasian Review of African Studies, 36(2), 22–50.

Ngubane, H. (1977). Body and mind in Zulu medicine: An ethnography of health and disease in Nyuswa-Zulu thought and practice. Academic Press.

Nyéléni Declaration on Food Sovereignty. (2007).

Pereira, L. (2014). The Future of South Africa’s Food System: What is research telling us? SA Food Lab.

Radu, I., Parent, É., Snowboy, G., Wapachee, B., & Beaulieu, G. (2020). Degrowth, decolonisation and food sovereignty in the Cree Nation of Chisasibi. In A. Nelson & F. Edwards (Eds.), Food for Degrowth (pp. 173–185). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003004820-17.

Roman-Alcalá, A. (2017). Looking to food sovereignty movements for post- growth theory. Ephemera, 17(1), 119–145.

Sachs, C., & Patel-Campillo, A. (2014). Feminist Food Justice: Crafting a New Vision. Feminist Studies, 40(2), 396–410. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2014.964217.

Shackleton, S. E., & Hebinck, P. (2018). Through the ‘thick and thin’ of farming on the Wild Coast, South Africa. Journal of Rural Studies, 61, 277–289. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2018.01.012.

Shiva, V. (2019). Earth Democracy: Sustainability, justice and peace. Buffalo Environmental Law Journal, 26(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.5070/g312310651.

Simpson, L. B. (2017). As We Have Always Done: Indigenous freedom through radical resistance. University of Minnesota Press.

Sustaining the Wild Coast NPC and Others v Minister of Mineral Resources and Energy and Others (3491/2021) ZAECMKHC (2022).

Tisani, N. (1992). The shaping of gender relations in mission stations with particular reference to stations in the East Cape frontier during the first half of the 19th century. Kronos, 19, 64–79.

Tomaselli, C., & de Wet, J. P. (2023). Policy on trial: Participatory vs neo-liberal development. Development Southern Africa, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/0376835X.2023.2252449.

Whyte, K. P. (2016). Indigenous Food Sovereignty, Renewal and U.S. Settler Colonialism. In The Routledge Handbook of Food Ethics (pp. 354–365). Routledge.

Winnie Madikizela Mandela Local Municipality. (2022). Integrated Development Plan 2022-2027.

Yamoah, D. A., De Man, J., Onagbiye, S. O., & McHiza, Z. J. (2021). Exposure of children to unhealthy food and beverage advertisements in South Africa. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(8), 3856. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18083856.

Zamchiya, P. (2019). Differentiation and development: The case of the Xolobeni community in the Eastern Cape, South Africa (61). Institute for Poverty, Land and Agrarian Studies (PLAAS).

Zukulu, S. (2012). Founding Affidavit. In the matter between Sinegugu Zukulu (First Applicant) and 5 others and the Minister of Water and Environmental Affairs (First Respondent) and 4 others in the High Court of South Africa (North Gauteng, Pretoria). Zukulu, S. (2022). Revenues and rural development. Transformation, 110, 110–116. https://doi.org/10.1353/trn.2022.a905645

[1] The food system is understood as the activities of food production, processing, distribution, and consumption and disposal, as well as the influence of the biophysical environment on these activities, and the governance and outcomes of these activities (Eriksen, 2013).

[2] We draw from the spelling in the local language and use Mpondoland for the territory and amaMpondo for the Mpondo people. In English, it is sometimes written Pondoland, and the Pondo. Amadiba are one of the groups that make up AmaMpondo, and Amadiba territory lies within Mpondoland.

[3] The phrase ‘actually existing alternative’ is commonly used in discussions of alternative economic systems to refer to contemporary, lived alternatives, rather than theoretical, imagined ones.

[4] While the concept of indigeneity can be complex in Africa, we agree with Canham (2023) in referring to amaMpondo as Indigenous people. This is also aligned to the way the African Court on Human and Peoples’ Rights has deployed the term in an African context (African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights, 2007).

[5] The villages are: Sigidi, Mdatya, Bhekela, Mtolani, Mpindweni, Nyavini and Gobodweni.

[6] Also referred to as the Mpondo Revolt or the Mpondo Uprising, and known in the local language, isiMpondo, as Nonqulwana.

[7] Eleven protesters were killed and 23 were arrested at Ngquza Hill on June 6th, 1960. Later that year a state of emergency was declared and hundreds more were arrested, with 30 people eventually sentenced to death in 1961 for their role in the Rebellion.

[8] A homestead is collection of structures (mostly rondavels, which are round huts, traditionally with thatched roofs) belonging to a single family, which may encompass several generations and may have anywhere from two to dozens of members.

9 / December / 2025

By: Gina D'Alesandro

8 / November / 2025

By: Mariana Calcagni G

19 / September / 2025

By: Taylor Steelman

19 / September / 2025

By: Eva Navarro

14 / June / 2025

By: Sarah Steinegger, Nora Katharina Faltmann