June / 14 / 2025

By: Sarah Steinegger, Nora Katharina Faltmann

Various grassroots initiatives that have emerged in recent decades reduce our dependence on large-scale industrial agriculture. They decouple food value from volatile markets through close producer-consumer relations, displaying potential for food system transformations towards post-growth. Community-Supported Agriculture (CSA) is an organizational form among them. While most CSAs cover short distances between farmers and consumers within (peri-)urban areas, this qualitative research focuses on an initiative in Switzerland that links rural mountains with urban areas. The study examines the role of institutional, organizational, cognitive, social, and experiential proximity among consumers and farmers in co-creating a food production and consumption system despite geographical distance. It found that consumers and farmers are facing challenges in establishing proximity; nevertheless, shared experiences of farming activities and social events, as well as participants’ willingness to improve the CSA operation and strengthen ties for mutual understanding and joint efforts, contribute to the ongoing process of establishing proximity.

Alternative Food Networks, Community-Supported Agriculture, post-growth, food, urban-rural relations

Calls for post-growth food systems, countering an increasing globalization and industrialization, concern not only a ‘localization’ or ‘re-spatialization’ but also a ‘re-socialization’. Food systems that aim to offer such an ‘alternative food geography’ (Wiskerke, 2009) or ‘spaces of possibility’ (Moragues-Faus & Marsden, 2017), reconnecting producers and consumers through grassroots initiatives, are often referred to as Alternative Food Networks (AFNs). AFNs provide “food markets that redistribute value through the network against the logic of bulk commodity production; that reconvene ‘trust’ between food producers and consumers; and that articulate new forms of political association and market governance” (Whatmore et al., 2003, p. 389). Research relates the alterity of AFNs to their form of organization, structural processes, as well as values (Blumberg et al., 2020). Community-Supported Agriculture (CSA) constitutes a form of AFN. According to the International Network for Community-Supported Agriculture (Urgenci, 2016b, p. 4), the core principles of CSAs encompass agroecological production methods and animal welfare, local knowledge, fair working conditions, community building, active participation, and solidarity, as well as accessible, fresh, local, seasonal, healthy, and diverse food. CSA initiatives hold these principles to varying degrees and manifest in various consumer-producer arrangements (e.g., Degens & Lapschieß, 2023). CSAs typically align the production capabilities of agricultural land with the number of people who can be nourished, forming the foundation for participants’ subscriptions or harvest shares (Urgenci, 2016a). In addition to increasing farmers’ security through advance payments and contractual acceptance guarantees, some CSAs expand the principle of solidarity to include consumers in farm labor, packaging, and transportation. Such ‘prosumption’ practices blur the roles of consumers and producers (Pineda Revilla & Essbai, 2022).

Current research highlights the high transformative potential of CSAs towards post-growth by co-creating a food production and consumption system among farmers and consumers: CSAs can reduce the dependence on large-scale industrial agriculture and decouple food value from volatile markets through shared risks, joint decisions, and farm labor among producers and consumers, as well as upfront financing for farmers and the distribution of actual yields to consumers (Blättel‐Mink et al., 2017; Bloemmen et al., 2015; Hvitsand, 2016; Pineda Revilla & Essbai, 2022). Along these lines, CSAs have been framed as commons due to the strong interdependencies between producers and consumers in their collective self-organization of food production and consumption systems (Cameron, 2015; Vivero-Pol et al., 2019).

We study a CSA[1] that was founded to support structurally disadvantaged mountain agriculture in Switzerland. Swiss mountain agriculture is heavily influenced by topographic and climatic conditions, such as elevated altitudes, shorter vegetation periods, and gradient slopes (Flury et al., 2013). Particularly in areas where arable farming is difficult or impossible, mountain farmers strongly rely on the extensive usage of grassland by ruminants (Spengler, 2020). Furthermore, mountain farmers encounter significant geographical distances to processing and distribution facilities (Flury et al., 2013). Due to these competitive disadvantages and usually smaller farm sizes, the production volumes and income levels in mountain agriculture are generally lower than those in lowlands agriculture, despite significant support from state subsidies (Hochuli et al., 2021). Meanwhile, mountain agriculture contributes to biodiversity, cultural landscapes, and the sustainable use of land that would otherwise be unsuitable for cultivation (Flury et al., 2013).

The spatial organization of the studied CSA – connecting consumers mostly living in urban areas with mountain farmers – and its product range, which requires processing, pose challenges. The studied CSA needs to find common grounds and master logistical challenges across regions that participants perceive to be considerable distances apart and associate with different ‘lifeworlds’. This CSA constitutes an atypical case (Flyvbjerg, 2006), as CSAs mostly involve short geographical distances between consumers and producers in urban and peri-urban areas and predominantly focus on vegetable production rather than processed products. Further, to the authors’ knowledge, CSA initiatives do not typically extend beyond regional boundaries and do not involve different socio-cultural contexts[2]. This article, therefore, aims to contribute to a discussion on how close consumer-producer relations – at the core of post-growth transformations – can be established despite such a challenging context of stretching across geographical distance and socio-cultural differences. We, therefore, ask: how do consumers and farmers co-create a food production and consumption system across rural mountain and urban areas and associated ‘lifeworlds’?

We operationalize the co-creation of a food production and consumption system across spatial distance and associated ‘lifeworlds’ with a proximity conceptualization that not only considers physical distance but also disentangles the relational dimensions of proximity. Previous research on inter-organizational coordination proposes proximity conceptualizations as the mechanisms allowing for interactive learning, innovation, conflict resolution, and the negotiation of divergent interests (Boschma, 2005; Knoben & Oerlemans, 2006; Torre & Rallet, 2005).

According to Boschma (2005), geographical proximity refers to the absolute and relative physical distance between actors, while cognitive, organizational, social, and institutional proximity are intangible attributes that overlap conceptually and empirically and might be grouped as relational proximity. Institutional proximity can be defined as a shared base of the rules of the game, values, and cultural norms, providing stable conditions for interactive learning. Organizational proximity refers to the governance structure and encompasses the shared formal relations within or between organizations that allow an exchange of knowledge and expertise, balancing flexibility and control in experimentation and knowledge sharing. Cognitive proximity facilitates mutual understanding and knowledge sharing, depending on the extent to which group members share the same knowledge base and expertise while allowing access to complementary knowledge domains and skillsets. Social proximity describes the degree to which economic relations are embedded in a social context. It facilitates tacit knowledge exchange, fostering trust-based social relationships and mutual commitment and experience. Notwithstanding, strongly pronounced social proximity can also diminish an organization’s learning ability. While geographical proximity is beneficial for conveying tacit knowledge and encourages interaction and collaboration, other forms of proximity based on intangible and relational aspects can serve as substitutes.

Proximity conceptualizations have been applied to the study of collective organizations and value chains in the agri-food sector (e.g., Dubois, 2018; Eriksen, 2013; Gugerell et al., 2021, 2022). Gugerell et al. (2021) adapted Boschma’s (2005) proximity conceptualization to sustainability innovation and operationalized it for CSAs’ attractiveness to members and outside actors. We consider their operationalization for CSA-internal proximity useful for our research: the case studied is a recent CSA initiative that is still in its infancy, undergoing experimentation with its day-to-day operations and the negotiation of its rules and values. Moreover, its reach extends across a geographical distance that participants perceive as influencing its everyday operations.

We complemented the operationalization of Gugerell et al. (2021) with the dimension of experiential proximity (see Table 1). We do so to account for consumer members’ direct involvement in agricultural work. Previous studies on CSAs emphasize that consumers’ participation in agricultural work results in added value to food through direct relationships with food and producers in the context of a local landscape (Geissberger & Chapman, 2023; Watson, 2020). This can counter consumers’ alienation from food origin and agricultural work (Watson, 2020). Furthermore, members can gain a new sense of agency as they perceive agricultural work as meaningful, embedded in a new social sphere characterized by practices of care for the environment and community interactions (Geissberger & Chapman, 2023).

| Proximity dimensions | Operationalization for food production and consumption systems |

| Geographical | Degree of spatial distance between participants |

| Institutional | Degree of collective establishment of institutions (i.e., rules and values) among participants, guiding the operation |

| Organizational | Degree of formal connections among participants in the organizational arrangement |

| Cognitive | Degree of shared knowledge and competencies among participants |

| Social | Degree of connections and personal acquaintance among participants (trust in each other and knowledge about each other) and social acceptance between participants |

| Experiential | Degree of participants’ direct involvement in agricultural work and experience with farm animals, plants, and soil in a particular landscape |

The Studied CSA

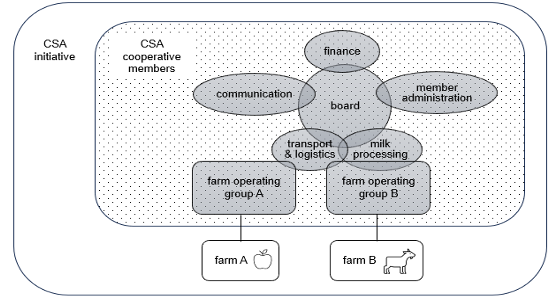

To the authors’ knowledge, among the approximately 70 CSA initiatives in Switzerland (Dyttrich & Hösli, 2015; Scharrer et al., 2023), the studied CSA is a pioneer in establishing a CSA initiative that spans both rural mountain and urban areas. The studied CSA was founded as a cooperative in April 2021 in a Swiss city. By 2023, it had around 50 consumer members who lived in the same city and its surrounding region, except for three members who lived in the region of the collaborating farms or elsewhere. Members include families with children and adults up to approximately 70 years old. In 2023, the CSA worked with two farms in a rural mountain area, each contributing a part of its farm operations (see Figure 1). Officially, the farmers are not members of the CSA cooperative but rather partners. An older farmer and his successor contribute fruit trees from their farm in the valley (Farm A). Another farmer couple, in their forties and fifties, participates with their Alpine farm[3] at 1900 meters altitude, which they operate in the summer, keeping around 70 goats for dairy and meat (farm B).

Membership is based on identification with the studied CSAs’ guiding principles, the purchase of cooperative shares, a yearly financial contribution, and participation in work activities—for either five to seven days per year for a minimum of three years, or two to three weeks within three years. Members have a variety of roles within the CSA, depending on their interests, skills, occupations, and available time. Their activities at the farms include goat herding and stable work (farm B), tree care, apple and pear harvest, and apple juice processing (Farm A), among other required tasks. The CSA responds flexibly to members’ ability to participate in the required work stays by involving them in the transportation of food products, administration, or communication. It also provides a solidarity fund for members with limited financial means. In return for their contributions to farm labor and finance, consumer members receive various products, including apple juice, fruits, goat and cow milk cheese, and goat meat, with some flexibility in the selection. The farmers participating in the studied CSA emphasized the importance of direct collaboration with consumers in maintaining their labor-intensive apple production and goat herding. They also highlighted that this collaboration facilitates the direct distribution of apple varieties, goat meat, and cheese, which would otherwise be challenging to commercialize.

Research Methods

Our research with this CSA initiative is based on an ethnographic methodology (Campbell & Lassiter, 2015) conducted between spring and winter 2023, triangulating participant observation, document analysis, and an interview. We conducted participant observation during a general assembly (28 members) and an extraordinary general meeting (33 members and a farmer) to gain insights into the CSA participants’ engagement in institution-building through decision-making and the negotiation of its purpose, as well as into social relations. We complemented these observations with the analysis of internal documents (website and bylaws). Participant observation during three agricultural work assignments at partnering farms provided insights into the CSA’s operational procedures, the practices and social dynamics characterizing work assignments, and the motivations of both consumers and farmers for participation. The first author attended the work assignment at Farm A in March (one day of work, including lunch with three farmers, eight members, and one prospective member). Together with the second author, they also attended a work assignment in October (dinner with six members, and one day of work, including lunch with two farmers, six members, and two prospective members). Furthermore, the second author conducted a fortnight-long research stay at Farm B in July, collaborating with two farmers and herding goats alongside four consumer members. To interpret the observed practices and dynamics and gather additional information, the first author conducted a qualitative interview with one of the initiators in December 2023. The authors then performed a content analysis (Schreier, 2012) of their notes, guided by the conceptual framework. Additionally, a master’s thesis, newspaper articles, and two documentaries featuring the CSA provided further context and information[4].

Geographical Proximity

In contrast to other CSAs (for Switzerland: Dyttrich & Hösli, 2015; Scharrer et al., 2023), geographical proximity between participating farmers and consumers is limited in the studied CSA. The vast majority of the 50 consumer members live in an urban area, except for three who reside in the same region as the partnering farms or elsewhere. Some have a personal connection to this mountain region, either having worked on a farm or Alp, or by regularly vacationing there, in some cases at their holiday homes. The farms’ locations require most members to travel by car or public transport for approximately two to three hours, making food storage, transportation, and distribution more complex than in other CSAs. The geographical distance, thus, necessitates both careful planning and adaptability to unforeseen circumstances.

Due to the perceived large geographical distance between the farms and most members’ homes, work assignments at the partnering farms are organized as extended stays, ranging from three days twice a year at Farm A to at least seven consecutive days at the goat Alp of Farm B (as of 2023). In the latter case, longer stays are required due to its remote location, which is only accessible via a two- to three-hour hike. The extended stays are also necessary given the nature of goat herding, as CSA members need time to become familiar with the goats and the surroundings of the Alp. Although these work stays involve financial costs and entail long-term planning as well as logistical difficulties, they are central to the CSA and establish temporary geographical proximity. Such temporary geographical proximity, along with other forms of proximity, can compensate for limited or absent general geographical proximity, as suggested in studies on proximity within organizations (Boschma, 2005; Knoben & Oerlemans, 2006; Torre & Rallet, 2005) and specifically within agri-food organizations (Edelmann et al., 2020; Gugerell et al., 2021, 2022).

Institutional Proximity

The CSA is founded on guiding principles that outline shared rules and values, establishing institutional proximity. According to an initiator, these guiding principles emerged from discussions and negotiations among the five initiators (some of whom are still members), various farmers from the mountain region, and workshop participants from diverse backgrounds. They continue to be discussed and refined. CSA membership is contingent upon agreement with these guiding principles, in addition to the binding financial contributions, which include yearly farm operation dues and the acquisition of a cooperative share certificate.

The guiding principles encompass the following: 1) similar to other CSAs (Urgenci, 2016a), direct cooperation among participants is envisioned to increase self-determination and sustainability in food production. This entails consumer participation in food production, as well as joint decision-making and planning between consumer members and farmers. 2) Continuity and commitment require consumers to sign up for a three-year contribution period, facilitating planning and direct marketing while establishing a binding relationship of solidarity among participants Membership to the studied CSA extends beyond the typical membership duration of 9-12 months (Urgenci, 2016a). Founding members specified that this requirement is linked to the goat herd (Farm B), whose size they do not want to adjust abruptly. However, this guiding principle remains contested. 3) As in other CSAs (see Urgenci, 2016a), prices are based on farm operation costs rather than on product unit prices. This enhances risk-sharing among participants, relieves farmers from price pressure, and guarantees stable farmer incomes. Overall, the guiding principles and the emphasis placed on them reflect the CSA’s aspirations to co-create a food system among its participants through ‘prosumption’ practices, joint decision-making, and solidarity.

Agreeing on shared rules and values extends the definition of guiding principles, as it is a dynamic process that involves becoming acquainted with the CSA’s day-to-day operations. This was evident during the studied CSA’s work assignments and the extraordinary general assembly, where participants raised numerous comments and questions and engaged in lively discussions. Members expressed differing opinions on applying and modifying existing rules and processes. These differing perspectives centered on the initiative’s economic sustainability, participant flexibility, transparency, and solidarity among members. Several motions were submitted to the assembly, calling for increased transparency through stricter regulations governing cooperation with the partnering farms and the cheesemakers. Additionally, some members proposed that the CSA should evaluate costs at every stage of the value chain and make unpaid work more visible.

In this context, a few members voiced concerns about a perceived imbalance in solidarity, particularly regarding the significant financial contributions and work commitments required of some members, sometimes tied to dissatisfaction with the taste of the cheese, which made them feel that their contributions outweighed what they received in return. Others stressed that members do not fully recognize that the farmers often step in at short notice and do not charge the CSA cooperative for all their labor. Some members and the farmer highlighted that the CSA is not a commercial enterprise but a solidarity-based initiative that requires compromises from everyone involved. As a result, it may not conform to conventional business relationships nor be subject to typical business analyses or economic rationalities. Previous research (Feagan & Henderson, 2009; Vaderna et al., 2022) suggests that balancing different expectations and orientations among CSA participants—such as idealism and pragmatism—requires transparency in workload distribution and a reciprocal understanding of needs, resources, and financial constraints among participants.

Organizational Proximity

Only consumers are CSA cooperative members with voting rights at the general assemblies, which limits organizational proximity between consumers and farmers. The farmers rely on cooperation contracts and implementation agreements with the cooperative, which define the financial contribution of the CSA cooperative to the farm operations, the type and intended quantity of food products, and members’ work assignments. The processors (i.e., two cheesemakers, the butcher, and the apple juice processor) do not have formal organizational ties to the CSA but are long-term partners of the farmers and take orders from them based on social relations and geographical dependencies.

Organizational proximity to the partnering farmers appears to be a core idea of CSAs and ‘prosumption’ practices. While farmers may be invited to attend the general assemblies in the city, they are regarded as guests and do not have voting rights. This imbalance stems from the partnering farmers granting the CSA consumers greater influence over idea development when the CSA was founded. Although farmers are not CSA members, they partake in decision-making in practice, such as negotiating contract terms and outlining their needs for work assignments. Admitting farmers as CSA members would further increase organizational proximity—a change advocated for by both the farmer and the majority of members at the extraordinary general assembly in 2023. This could lead to a more equitable distribution of risks, responsibilities, and decision-making power between farmers and consumers. Indeed, previous research (Raj et al., 2023) suggests that creating post-capitalist, non-alienated work relations requires dismantling CSA internal hierarchies and decentralizing decision-making within CSAs.

The CSA provides various formal connections among its members, fostering organizational proximity among consumer members. The organizers (grey elements in Figure 1) operate with a board, two farm operating groups, and five working groups. Operational decisions are delegated to the working groups and the two operating groups, which liaise with the partner farms and processors and organize work assignments at the farms. The board is responsible for overseeing these operational decisions. Additionally, board members participate in working and/or operating groups, giving them a comprehensive overview of CSA activities and their interconnections while strengthening organizational proximity among the organizers. The board also ensures that higher-level decisions, such as the annual budget, are presented to the general assembly for approval and are subsequently implemented.

However, as Figure 1 illustrates, there are multiple overlaps between the working groups and farm operating groups. For instance, the farm operating group B, along with the working groups for transport and logistics and milk processing, communicates with the cheesemakers and/or the butcher in consultation with the farmers. Reducing these overlaps could improve communication flow and reduce workload. Furthermore, at the extraordinary general assembly in 2023, CSA members acknowledged the need for additional platforms to facilitate exchange between organizers and regular members. Similarly, other studies highlight the importance of improving information flow between CSA organizers and regular members and promoting a more balanced distribution of tasks and responsibilities among all participants (Raj et al., 2023). Thus, while a more extensive interface between regular members and organizers will require greater coordination, it could also help resolve operational challenges by allowing regular members to contribute to problem-solving and alleviate the burden on organizers.

Cognitive Proximity

The complex operation of the studied CSA requires a broad repertoire of skills and a shared base of knowledge and competence to foster cognitive proximity and, eventually, effective collaboration. Several members have prior experience with farming – including Alpine farming – through part-time or seasonal employment, civilian service, and volunteer work. Furthermore, most members repeatedly complete their work assignments at one of the farms and exchange tips and tricks with others. Thanks to their experience, their exchange with less experienced members, and written documentation of instructions for work stays, farmers are not always required to provide comprehensive explanations of tasks to everyone during the work assignments. One CSA member has also acquired knowledge of cheese-making to support cheese production at the Alpine pasture operation that collaborates with the CSA. Members’ farming and cheese-making experiences thus contribute to a shared knowledge base among themselves and the partnering farmers and cheesemakers, which facilitates collaboration.

Members from diverse backgrounds and age groups also contribute expertise in various domains, such as accounting, logistics, and communication. For the creative power of collaborative knowledge production to emerge, the CSA must integrate farming and food processing experience with these complementary skills (Degens & Lapschieß, 2023). While the diverse knowledge and experience of CSA participants primarily benefit its operation, they can sometimes lead to challenges. Partnering farmers regularly emphasize that farming and food processing require constant flexibility in response to uncontrollable factors such as the weather or animal health and behavior. Meanwhile, members usually require more advanced planning for their work assignments and for coordinating the logistical interfaces involved in processing and transporting food products. As most members do not live locally and must integrate their CSA commitments with other activities, some have requested that logistical handovers be adhered to more strictly. This reflects the differing daily realities of farmers and consumers and the challenge of aligning their expectations regarding spontaneity and planning (Vaderna et al., 2022). Nevertheless, one member improved communication among members, farmers, cheesemakers, and the butcher by acting as an intermediary. This member regularly visited the farmers, cheesemakers, and butcher, relaying wishes and concerns back to members to improve mutual understanding of what she described as the different ‘lifeworlds’ of participants in urban and rural mountain areas, respectively.

Social Proximity

Social proximity emerges in the context of annual formal meetings, quarterly product pick-up days, regular organizational meetings, and agricultural work stays.

Formal decision-making meetings – the general assemblies and meetings of the working and operating groups – are embedded in social interactions, contributing to social proximity. General assemblies are accompanied by snacks and drinks, encouraging socializing among participants. Similarly, dinners are held at members’ homes during working and operating group meetings to ensure that discussions on the CSA’s operation feel more like leisure. This suggests that the CSA constitutes a community of individuals with strong social cohesion. This may be related to the fact that organizing groups are predominantly built on a pre-existing friend group. The strong social proximity among the members of this CSA contrasts with the findings of Vaderna et al. (2022), who found that consumers participating in Swiss CSAs – unlike farmers – tend to perceive the CSA community as an interest group, displaying little interest in social interaction. Nevertheless, not all members of the studied CSA seek strong social ties, and social proximity among members is not uniform. Furthermore, the strong social proximity among the organizers of the studied CSA may have exclusionary effects on other members and hinder the CSA’s capacity to incorporate diverse experiences and inputs.

Although pick-up days occur three times a year, which is less often than in vegetable CSAs, they still serve an important social function by allowing face-to-face and informal exchanges among members. Sometimes, pick-up days also extend into longer social gatherings, like barbecues, which the members appreciate as moments of social closeness. Thus, instead of being mere points of food transaction, food pick-up days are accompanied by shared meals and conversations about experiences with goat herding and fruit harvest. This aligns with previous studies that identified food pick-up—along with agricultural work—as a key moment in fostering social relationships among CSA participants (Hayden & Buck, 2012; Liu et al., 2017; Savarese et al., 2020). Furthermore, the social dimension of food pick-up days reflects that the alternative organization of labor and food provision in CSAs foregrounds multiple values of food and associated work, rather than subordinating them to their exchange value (Watson, 2020).

The work stays mark concentrated periods spent together, during which social connections and personal acquaintance among participants develop and intensify, fostering social proximity. As members usually undertake work stays at one of the participating farms, social interaction, mutual commitment, and a sense of trust tend to be more concentrated in the relationships among those who share a common experience of agricultural work. This is in line with previous research on CSAs, which emphasizes the impact of participants’ collaboration on consumers’ appreciation of farmers and their work, and the development of trust-based relationships (Geissberger & Chapman, 2023; Watson, 2020). Furthermore, it reflects the ability of CSAs to foster a sense of community belonging through the voluntary dedication of participants to a shared purpose (Liu et al., 2017).

Experiential Proximity

While the work stays contribute to various proximity dimensions within the CSA, consumers’ participation in agricultural work also provides them with direct experience of food production, farm animals, plants, and soil in specific landscapes. This experiential proximity is especially evident in the studied CSA, where most members undertake work stays lasting between three days and two weeks. In particular, herding goats for a week or more creates an intimate experiential connection with the Alp and the goats. As some members noted in a discussion about goat meat, familiarity with the animals can be challenging for some, as the slaughtering of animals they know and care for becomes more tangible than what most consumers are accustomed to. Others value this proximity, including some vegetarians, who stated that they make a dietary exception for the CSA’s goat meat. In general, members emphasize that they participate in the CSA because they seek a deeper understanding of farming and food production. They also appreciate physical work in the mountain terrain and the direct engagement with the farms from which they consume. Involvement in agricultural labor can thus mediate other values of food than its physical and tangible qualities (Watson, 2020), such as an attachment to a place, landscape, farm, or animal.

This attachment through experiential proximity includes a temporal component as it builds over time. Longer-term members tend to have stronger ties to the studied CSA than those without first-hand experience at the farms. This reflects previous research on CSAs, which suggests that consumers’ direct experience of agricultural work and sensory involvement transforms their relationship to the environment, food, agriculture, and fellow participants, fostering environmental-ethical linkages (Geissberger & Chapman, 2023; Hayden & Buck, 2012; Savarese et al., 2020; Watson, 2020). Consumers’ experience with farm animals, plants, and soil in specific landscapes might thus influence their willingness to co-create the CSA’s operation.

The fact that the CSA collaborates with farmers in rural mountain areas shapes experiential proximity. Members must immerse themselves in and adapt to the biophysical conditions of mountain areas, especially when herding goats. Even experienced goat herders reported that they had to get used to navigating and walking up and down the steep slopes over the considerable distances that goats cover during grazing. Members describe herding as physically demanding but also appreciate its restorative value in connecting with the animals and the landscape. Moreover, they find it a welcome escape from their everyday lives and perceive it as a purposeful activity. CSA members attribute the meaningfulness of goat herding to their individual and the CSA’s collective responsibility toward the well-being of the animals, the importance of herd protection, and the farmers’ challenges in organizing and financing the associated labor. Furthermore, the members who work at Farm A highly value the labor and care required for arboriculture. Thus, the embodied experience of consumers with hard agricultural work establishes a sense of their contribution to the maintenance of low-input, labor-intensive, and place-adapted agriculture, as well as to the well-being of farm animals and farmers (Liu et al., 2017).

In this article, we used multiple proximity dimensions to examine the co-creation of a food production and consumption system across rural mountain and urban areas and the associated ‘lifeworlds’ by a CSA. The studied CSA constitutes an organization of ‘prosumers’ (farmers and consumers) who balance their expectations and abilities, enhancing organizational and institutional proximity through experimentation. Through temporary geographical proximity—spending time together and shaping spaces—the CSA further fosters cognitive, social, and experiential proximity. It generates interactions among consumers and farmers, transforming them into ‘prosumers’ (Hayden & Buck, 2012; Liu et al., 2017; Savarese et al., 2020). As suggested by other studies, joint decision-making among CSA consumers and farmers, along with consumers’ takeover of responsibilities, counters their alienation from agricultural labor and food, enhances their appreciation of farmers’ work, and disrupts unequal consumer-producer relationships (Raj et al., 2023; Watson, 2020). Knowledge about food production is transmitted through interpersonal relationships and direct experience over time, creating a shared knowledge and experience base about food quality and origin (Dubois, 2018; Geissberger & Chapman, 2023).

Due to its geographical setup, an imbalance in decision-making, and different expectations of participants, the studied CSA faces challenges in creating proximity. However, its members and farmers display a strong willingness to improve the CSA operation and strengthen ties for mutual understanding and joint efforts through negotiating diverse expectations during ongoing discussions. A food system based on proximity among farmers and consumers indeed depends on participation, interaction, and reciprocal relations based on collaboration and mutual benefits (Galt, 2013; Grasseni, 2014; Pineda Revilla & Essbai, 2022). This embeds food production and consumption into social relations and contributes to post-growth transformations (Blättel‐Mink et al., 2017; Bloemmen et al., 2015; Feagan & Henderson, 2009). Like in other CSAs, the ‘learning by doing’ approach of participants and the dynamic development of the studied CSA imply a high level of reflexive resilience in terms of participants’ awareness of challenges and adaptive capacity. This may play a pivotal role in enabling the studied CSA to reach its full transformative potential, particularly regarding the actual participation of farmers and consumers—representing various socio-economic groups—in decision-making processes (Degens & Lapschieß, 2023).

In particular, consumers’ first-hand experience with farm animals, plants, and soil in a specific landscape can enhance their perception of engaging in meaningful activities and thereby contribute to the maintenance of extensive agriculture and landscape stewardship (Geissberger & Chapman, 2023; Hayden & Buck, 2012), which is highly relevant in the context of mountain agriculture. To account for this immediate experiential involvement of members, we added experiential proximity as a proximity dimension influencing the co-creation of the studied CSA’s food system. While the proximity dimensions are interdependent, we call for further research to examine whether experiential proximity predetermines how farmers and consumers interact, influencing social, cognitive, organizational, and institutional proximity. We assume that, in particular, the blurring of the boundaries between production and consumption spaces through experiential proximity in CSAs can contribute to “rebuilding connections between the urban and the rural” (Pineda Revilla & Essbai, 2022, p. 184). Thus, experiential proximity might also hold potential for other AFNs and ‘prosumption’ practices.

The studied CSA is a small and dynamic initiative with a unique set-up connecting urban and rural mountain areas. From a methodological perspective, this poses challenges in gaining access to and keeping up with ongoing discussions while also avoiding participants’ research fatigue. Nevertheless, our positionality and participatory methodology facilitated close relations with research participants and helped mitigate the extensive time required for study participation. It also involved a dialogue about the subjectivity of research, which relates to the anonymization of the CSA initiative. We suggest that, despite—or perhaps because of—its particular spatial configuration, the studied CSA can be seen as a space of experimentation. Its ongoing formation and negotiations may serve as a testing ground for post-growth food systems (Bloemmen et al., 2015; Moragues-Faus & Marsden, 2017), especially for fostering close consumer-producer relationships across spatial distances and different ‘lifeworlds’.

A heartfelt thank you to all research participants for sharing your experiences. We are also grateful to our colleagues Carla Scheytt, Katharina Mojescik, Paul Froning, Rike Stotten, Sarah von Karger, Thea Wiesli, and Ottavia Cima for your valuable feedback on an earlier version of this article. Thank you to the two reviewers for your constructive comments, and the editorial team from the JPE Grassroots section and the special issue – not only for your careful editorial work but also for facilitating enriching discussions. This research was funded in part by the Institute of Geography and the Centre for Regional Economic Development (CRED) at the University of Bern and in part by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF) [10.55776/ZK64].

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this article.

During the preparation of this work, the first author used DeepL Write and Grammarly to enhance the text’s clarity. After using these tools, the authors reviewed and edited the content, and take full responsibility for the publication’s content.

Agroscope. (2024). Focus Alpine farming. Agroscope. Retrieved February 1, 2025, from https://www.agroscope.admin.ch/agroscope/en/home/topics/environment-resources/biodiversity-landscape/agrarlandschaft/focus-alpine-farming.html

Beach, D., & Pedersen, R. B. (2018). Selecting appropriate cases when tracing causal mechanisms. Sociological Methods and Research, 47(4), 837–871. https://doi.org/10.1177/0049124115622510

Blättel‐Mink, B., Boddenberg, M., Gunkel, L., Schmitz, S., & Vaessen, F. (2017). Beyond the market—New practices of supply in times of crisis: The example community‐supported agriculture. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 41(4), 415–421. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcs.12351

Bloemmen, M., Bobulescu, R., Le, N. T., & Vitari, C. (2015). Microeconomic degrowth: The case of community supported agriculture. Ecological Economics, 112, 110–115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2015.02.013

Blumberg, R., Leitner, H., & Cadieux, V. (2020). For food space: Theorizing alternative food networks beyond alterity. Journal of Political Ecology, 27(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.2458/v27i1.23026

Boschma, R. (2005). Proximity and innovation: A critical assessment. Regional Studies, 39(1), 61–74. https://doi.org/10.1080/0034340052000320887

Cameron, J. (2015). Enterprise innovation and economic diversity in community supported agriculture: Sustaining the agricultural commons. In J. K. Gibson-Graham, G. Roelvink, & K. St Martin (Eds.), Making other worlds possible: Performing diverse economies (pp. 53–71). University of Minnesota Press. https://doi.org/10.5749/j.ctt130jtq1

Campbell, E., & Lassiter, L. E. (2015). Doing ethnography today: Theories, methods, exercises. Wiley Blackwell.

Degens, P., & Lapschieß, L. (2023). Community-supported agriculture as food democratic experimentalism: Insights from Germany. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems, 7(1081125), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsufs.2023.1081125

Dubois, A. (2018). Nurturing proximities in an emerging food landscape. Journal of Rural Studies, 57, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2017.10.005

Dyttrich, B., & Hösli, G. (2015). Gemeinsam auf dem Acker: Solidarische Landwirtschaft in der Schweiz. Rotpunktverlag.

Edelmann, H., Quiñones‐Ruiz, X. F., & Penker, M. (2020). Analytic framework to determine proximity in relationship coffee models. Sociologia Ruralis, 60(2), 458–481. https://doi.org/10.1111/soru.12278

Eriksen, S. N. (2013). Defining local food: Constructing a new taxonomy – three domains of proximity. Acta Agriculturae Scandinavica, Section B – Soil & Plant Science, 63(sup1), 47–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/09064710.2013.789123

Feagan, R., & Henderson, A. (2009). Devon acres CSA: Local struggles in a global food system. Agriculture and Human Values, 26(3), 203–217. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-008-9154-9

Flury, C., Huber, R., & Tasser, E. (2013). Future of mountain agriculture in the Alps. In S. Mann (Ed.), The future of mountain agriculture (pp. 105–126). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-33584-6

Flyvbjerg, B. (2006). Five misunderstandings about case-study research. Qualitative Inquiry, 12(2), 219–245. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800405284363

Galt, R. E. (2013). The moral economy is a double‐edged sword: Explaining farmers’ earnings and self‐exploitation in community‐supported agriculture. Economic Geography, 89(4), 341–365. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecge.12015

Geissberger, S., & Chapman, M. (2023). The work that work does: How intrinsic and instrumental values are transformed into relational values through active work participation in Swiss community supported agriculture. People and Nature, 5(5), 1649–1663. https://doi.org/10.1002/pan3.10531

Grasseni, C. (2014). Seeds of trust. Italy’s Gruppi di Acquisto Solidale (Solidarity Purchase Groups). Journal of Political Ecology, 21(1), 178–192. https://doi.org/10.2458/v21i1.21131

Gugerell, C., Edelmann, H., & Penker, M. (2022). Nahe Ferne, weite Nähe? Ein Analyserahmen für Dimensionen der Nähe in lokalen und transkontinentalen alternativen Lebensmittelnetzwerken. In M. Larcher & E. Schmid (Eds.), Alpine Landgesellschaften zwischen Urbanisierung und Globalisierung (pp. 193–208). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-36562-2

Gugerell, C., Sato, T., Hvitsand, C., Toriyama, D., Suzuki, N., & Penker, M. (2021). Know the farmer that feeds you: A cross-country analysis of spatial-relational proximities and the attractiveness of community supported agriculture. Agriculture, 11(1006), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture11101006

Hayden, J., & Buck, D. (2012). Doing community supported agriculture: Tactile space, affect and effects of membership. Geoforum, 43(2), 332–341. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2011.08.003

Hochuli, A., Hochuli, J., & Schmid, D. (2021). Competitiveness of diversification strategies in agricultural dairy farms: Empirical findings for rural regions in Switzerland. Journal of Rural Studies, 82, 98–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2021.01.021

Hvitsand, C. (2016). Community supported agriculture (CSA) as a transformational act—Distinct values and multiple motivations among farmers and consumers. Agroecology and Sustainable Food Systems, 40(4), 333–351. https://doi.org/10.1080/21683565.2015.1136720

Immovilli, M. (2023). A glimpse into CSA Cresco: Cultivating food for broader transformative change in mountain territories.Journal of Alpine Research | Revue de Géographie Alpine [online]. https://doi.org/10.4000/rga.11036

Knoben, J., & Oerlemans, L. A. G. (2006). Proximity and inter‐organizational collaboration: A literature review. International Journal of Management Reviews, 8(2), 71–89. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2370.2006.00121.x

Liu, P., Gilchrist, P., Taylor, B., & Ravenscroft, N. (2017). The spaces and times of community farming. Agriculture and Human Values, 34(2), 363–375. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-016-9717-0

Moragues-Faus, A., & Marsden, T. (2017). The political ecology of food: Carving ‘spaces of possibility’ in a new research agenda. Journal of Rural Studies, 55, 275–288. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2017.08.016

Pineda Revilla, B., & Essbai, S. (2022). Towards a post-growth food system: The community as a cornerstone? Lessons from two Amsterdam community-led food initiatives. In F. Savini, A. Ferreira, & K. C. von Schönfeld (Eds.), Post-growth planning: Cities beyond the market economy (pp. 173–186). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003160984

Raj, G., Feola, G., & Runhaar, H. (2023). Work in progress: Power in transformation to postcapitalist work relations in community–supported agriculture. Agriculture and Human Values, 41, 269-291 https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-023-10486-8

Savarese, M., Chamberlain, K., & Graffigna, G. (2020). Co-creating value in sustainable and alternative food networks: The case of community supported agriculture in New Zealand. Sustainability, 12(1252), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12031252

Scharrer, B., Hett, C., & Mann, S. (2023).Alternative Wertschöpfungsketten und Wege der Vertrauensbildung—Jenseits von Zertifizierungssystemen und Labels (pp. 1–24) [Working Paper]. University of Bern, Centre for Development and Environment. https://boris.unibe.ch/178517/1/Scharrer_et-al_2023-Feb_Alternative_Wertsch_pfungsketten.pdf

Schreier, M. (2012). Qualitative content analysis in practice. Sage. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781529682571i

Spengler, A. (2020). Wiesen, Weiden, Wiederkäuer—Was die Schweizer Berglandwirtschaft für die Umwelt leistet (pp. 1–7). FiBL. https://orgprints.org/id/eprint/38198/1/spengler-2020-Wiesen-Weiden-Wiederkaeuer.pdf

Torre, A., & Rallet, A. (2005). Proximity and localization. Regional Studies, 39(1), 47–59. https://doi.org/10.1080/0034340052000320842

Urgenci. (2016a). Overview of community supported agriculture in Europe (pp. 1–138). Urgenci: The International network for community supported agriculture. https://urgenci.net/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/Overview-of-Community-Supported-Agriculture-in-Europe-F.pdf

Urgenci. (2016b). Towards a European CSA Declaration (pp. 1–5). Urgenci: The International Network for Community Supported Agriculture. https://urgenci.net/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/Declaration-writing-process-2015-16.pdf

Vaderna, C., Home, R., Migliorini, P., & Roep, D. (2022). Overcoming divergence: Managing expectations from organisers and members in community supported agriculture in Switzerland. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 9(105), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-022-01115-6

Vivero-Pol, J. L., Ferrando, T., De Schutter, O., & Mattei, U. (2019). Routledge handbook of food as a commons. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315161495

Watson, D. J. (2020). Working the fields: The organization of labour in community supported agriculture. Organization, 27(2), 291–313. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350508419888898

Whatmore, S., Stassart, P., & Renting, H. (2003). What’s alternative about alternative food networks? Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 35(3), 389–391. https://doi.org/10.1068/a3621

Wiskerke, J. S. C. (2009). On places lost and places regained: Reflections on the alternative food geography and sustainable regional development. International Planning Studies, 14(4), 369–387. https://doi.org/10.1080/13563471003642803

[1] For anonymity reasons, we do not refer to the studied CSA by its name.

[2] To the knowledge of the authors, another CSA in an Italian mountain area has been studied by Immovilli (2023), but this case does not display the outlined characteristics.

[3] Alpine farms or Alps account for one-third of agricultural land cultivated in Switzerland (Agroscope, 2024). They constitute summering areas, including mountain pastures, farm buildings, and infrastructure (e.g., milk processing) used during the summer months.

[4] The references are not provided for anonymity reasons.

9 / December / 2025

By: Gina D'Alesandro

8 / November / 2025

By: Mariana Calcagni G

19 / September / 2025

By: Taylor Steelman

19 / September / 2025

By: Eva Navarro

14 / June / 2025

By: Sarah Steinegger, Nora Katharina Faltmann