January / 1 / 2024

By: Atak Ayaz

This article explains the social and economic changes that transpired in Turkey’s rural areas by focusing on a vigneron village in the country’s northwest. My goal is to show that the neo-liberalization of Turkey’s economy in the 1980s and the privatization of state-owned production facilities in the 2000s exacerbated the devaluation of farmers’ products and the depreciation of their labor. As a result of income unpredictability and an aging population, agrarian communities have either turned their vineyards into olive groves or uprooted them. Meanwhile, since the early 2000s, grape cultivation in Turkey has entered a wine-oriented phase primarily led by urbanites from non-agricultural sectors. Even though the percentage of wine grapes has increased in recent years, they mostly come from newly established vineyards of a new class of wine entrepreneurs. Based on 13 months of ethnographic research in vineyards and small-scale wineries in Turkey’s Thrace, I argue that the peasantry in Turkey is in a transition that poses an indeterminate future for the country’s grape cultivation and vineyard areas.

Key Words: Grape cultivation; Viticulture; Winemaking; Viniculture; Peasant Class; Neo-liberalization; Turkey

This article tells the story of a young olive tree in a vineyard. This narrative reveals the political economy behind what might be seen simply as a tree out of place. Although Turkey is among the top five countries in terms of vineyard area (Figure 1; Akdemir & Candar, 2022), vignerons cultivating grapes for generations are uprooting their vineyards and, climate-allowing, turning them into olive groves. Olive trees in former vineyards symbolize the agony of the lost economic viability of grape cultivation for an aging agricultural community in Thrace, a region in northwestern Turkey that borders Greece and Bulgaria, whose economy is primarily based on grape cultivation—viticulture. Building on 13 months of ethnographic research—during which I studied the tensions and negotiations among grassroots farmers, a new class of urbanite wine entrepreneurs, and state institutions—this article focuses on grape cultivation’s unpredictable and precarious state. Situating the state’s economic planning of production in its enterprises as the leading actors, my goal is to show that the shift from a statist economy to a neo-liberal order based on private production facilities was a turning point in the reshaping of the viticultural areas in Turkey.

Figure 1: Highest ten countries in terms of vineyard area and grape production in the world in 2020 (FAO, 2022 in Akdemir & Candar, 2022)

Even though this article describes how a young olive tree wound up in a vineyard, the text focuses mainly on grapes. Despite many vineyards, which have been active in farming for generations, being filled with young olive trees—a sign of the decline in viticultural areas—Turkey’s wine industry took an unparalleled turn towards higher quality in the late 1990s and early 2000s. This transformation occurred, paradoxically, after the privatization of the state monopoly known as TEKEL.

TEKEL, or the Régie or Monopoly as it was called, was a joint foreign and Ottoman consortium formed in 1862. It was short for La Société de la Régie Co-Intéressée des Tabacs de l’Empire Ottoman. As the Ottoman Empire struggled to make payments on its international debt, two French companies were founded as a monopoly controlling the tobacco and cigarette trade: Régie Compagnie interessee des tabacs de l’empire Ottoman and Narquileh tobacco. At first, the monopoly sought to deal only in tobacco products, but its scope eventually expanded, and Régie started controlling all trade, finance, and manufacturing of tobacco in the empire. After the collapse of the Ottoman Empire and the establishment of the Republic of Turkey in 1923, Régie was nationalized in 1925 and became TEKEL. The duty of controlling the ‘monopoly’ tasks for tobacco, alcoholic drinks, salt, gunpowder, and explosives was given to the Monopolies Public Directorate, founded in 1932. Tobacco, alcoholic drinks, and salt were then subsumed under the state monopoly in 1932, gunpowder and explosives in 1934, beer in 1939, tea and coffee in 1942, and matches in 1946. Over the years, different products were released by TEKEL so as not to block private investments. Coffee was released from the state monopoly in 1946, matches in 1952, gunpowder and explosives and beer in 1955, and tobacco in 1986. In 2003, the Directorate of Privatization Administration decoupled the cigarette and alcohol departments and privatized them.

TEKEL was the umbrella company/governmental office that would come to encompass several wineries and distilleries. Therefore, the company impacted the agricultural production of grapes, barley, hop, anise (aniseed or Pimpinella anisum), and other crops used in producing fruit-based liquors. Even though the institution’s name (TEKEL) meant monopoly, wine was never monopolized in Turkey. Along with the stateowned wineries, private ones were established with governmental incentives. Economic historians Fatma Doğruel and A. Suut Doğruel, who published a comprehensive book on the history of TEKEL, read this mixed economy system in light of the religious identities of the newly established republic’s citizens. They write: “One of the reasons for this [allowing private firms to be a part of the production sphere alongside the state-run firm] was to break the conservatism stemming from the religious motives; not to let citizens seek for alternative crops other than grapes” (Doğruel & Doğruel, 2000, p.86). Given that the two foundational pillars of the Turkish Republic are laicism (excluding religious visibility from the public domain) and statism (political authority of the state in social and political policies), TEKEL, as a state-owned institute, aimed to boost both. Although alcohol production is not necessarily a goal of laicism per se, the urge to stand against Islamist pushback for prohibiting alcohol consumption facilitated the binding of these two foundational pillars.

To develop grape cultivation and winemaking, which happens to be one of its subsidiary industries, TEKEL was an active institution that oversaw various aspects of production in the country. To develop the wine industry, the ‘sample wine houses (örnek şarap evleri)’ project was realized in the 1940s. In its scope, The General Directorate of TEKEL established pilot wine venues in various locations within Turkey that had extensive vineyards areas. Elazığ, Ürgüp, Kayseri, Bilecik, Yozgat, Gaziantep, Çorum, Nevşehir, Bor, Kalecik, Kırşehir, Kırıkkale, Kırcasalih, Şarköy, Hoşköy, Uçmakdere, Tokat, Kahraman are the cities/districts where some of these pilot houses were situated. As Kerim Yanık, former director of one, explains in his memoir, the presence of state-owned facilities not only allowed wine production to prosper in the country, but had an effect on agriculture. (Yanık, 2019).

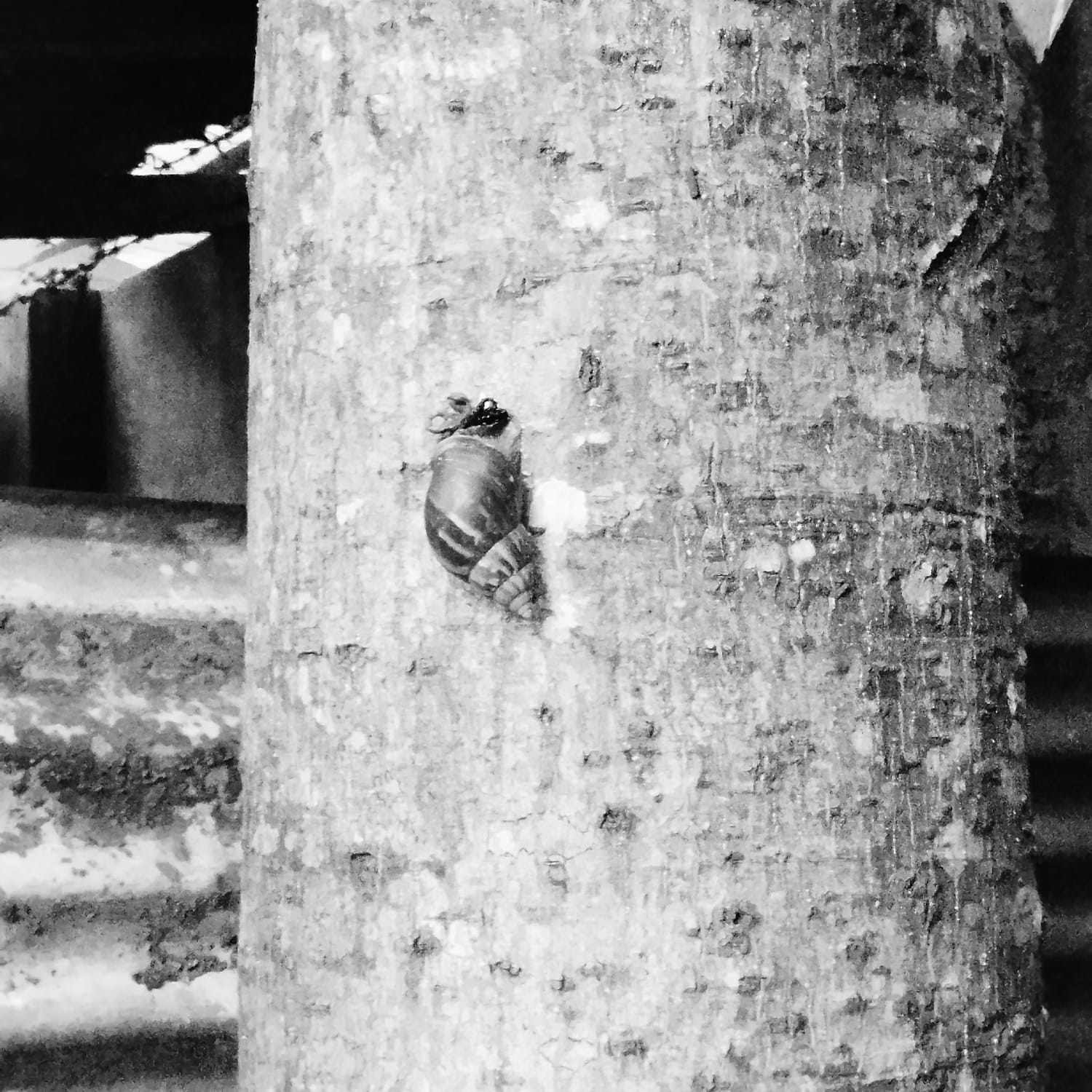

It was a sunny January morning when I met Alpay and Kemal—two of the people I worked with in a winery in Turkey’s northwest during my fieldwork. As co-workers, we were divided into two groups. Kemal, Alpay, and I took care of vineyard-related issues, while the others focused on the daily business at the winery, such as collecting orders, preparing bottles, and selling wine. When we entered the village where Alpay’s vineyards are located, we drove along the meandering pebble-stone road to the upper part of the village to visit the new vineyard. After parking the car and walking toward the vineyards Alpay had purchased, I noticed the smell of manure, primarily due to animal husbandry in the village and because some people had already manured their vineyards. We passed by other vineyards and olive groves to reach the plot. It was at that moment I noticed young olive trees interspersed within the vineyards (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Young olive tree in a vineyard. The photo belongs to the author.

Following current literature that highlights how plants are used as boundary makers (Besky & Padwe, 2016; Blomley, 2007; De León, 2015; Griffin, 2008), I initially assumed the olive trees marked the vineyard’s borders. However, I soon realized they were scattered in various spots—not only at the edges, but also right in the middle. As the sight of olive trees within vineyards was new to me, I wanted to understand how they may affect the grapes and asked questions about the logic of this decision. Surprisingly, the presence of olive trees amidst the vineyards was nothing new for Alpay and Kemal. They calmly explained that the olive trees do not affect grapes in the initial years, and people are happier as they can make money through both grapes and olives. However, as the trees mature, their shadows gradually envelop the grapes, hindering the development of the berries. Consequently, the grapes are eventually uprooted, and the land transforms into an olive grove.

This is a village whose livelihood was based primarily on fishing, tobacco production, and cultivating and harvesting grapes—viticulture. It is mainly inhabited by people who migrated to Turkey due to the forced population exchange between Turkey and Greece in 1923-1924. [2] Even though one of the biggest olive cooperatives in Turkey is only 15 kilometers from the village, [3] the region is famous for its grapes—a fact also celebrated in Turkish folk songs. Grape cultivation is so deeply ingrained in the inhabitants’ lives that several streets in villages and towns of this region are named after grape varieties – Şensu, [4] Yapıncak, and Gamay. However, the land dedicated to grape cultivation has decreased over the years. Kemal, who comes from a family that has cultivated grapes for generations, explained that the acreage of vineyards in the region was much larger twenty to thirty years ago. The olive groves were all once vineyards. Later, others in the same region also mentioned that they used to walk through the vineyards when going to school. Nowadays, these lands have been turned into olive groves or summer houses.

To better understand why I encountered a young olive tree in a vineyard, I specifically asked when the practice began. Kemal clarified that the privatization of the state monopoly TEKEL in 2003-2004 triggered this transition. Before privatization, TEKEL was the biggest alcohol producer in the country, thus predominantly dictating the price of grapes per kilogram. TEKEL’s wineries and distilleries produced various kinds of alcohol by purchasing raw materials—grapes, anise, and other fruits—from villagers. By doing so, the state-owned facilities not only dominated the market but also boosted rural development by creating a market for agrarian products.

During the TEKEL era, just before the start of harvest, officials would visit vineyards to assess the grapes’ sugar levels. Pricing was determined based on the Baumé hydrometer readings, which showed the dissolved sugar content. However, regardless of the varying sugar levels among grapes, grape prices would increase in line with the annual inflation rate. Vignerons knew that their income would undoubtedly rise. Furthermore, owing to the technical support and payment guarantees from government agencies, private wineries had to offer higher prices compared to the state-owned institution to entice vignerons into selling their grapes. However, after the neo-liberal turn in Turkey’s economy and the subsequent wave of privatization during the 2000s, individual wineries became the exclusive buyers of grapes from local cultivators.

In other words, when the monopoly controlling the price mechanisms was dissolved, Turkey’s wine production per liter experienced a sharp decline. This resulted in an excess of grapes left in vineyards awaiting buyers. Consequently, prices depended on private wineries’ “demand and offer.” From that point forward, vignerons have been unable to predict whether prices would remain stable, rise, or fall until grape traders visited the vineyards and major wine producers announced their offers.

Due to changing state policies that impacted villagers’ income, people began searching for new crops to establish more stable earnings. Although grape cultivation has the potential to generate more revenue than cultivating olives, as Kemal stated, it comes with precarity and uncertainty. As a result, several vignerons have uprooted their vineyards and planted olive trees in Turkey’s northwest, primarily to secure their families’ income.

I visited various vine-growing villages in Turkey’s Thrace to understand the transitions in rural economies better. In 2019, just before harvest began, I was in the same village to observe how vignerons were preparing for the tumultuous and grueling days ahead. I met the vignerons at the football field, which was less than a kilometer from the village center. A large truck full of crates was present, while vignerons awaited with their small tractors to transport them to their vineyards (Figure 3). Each vigneron carried a certain amount to their vineyards, depending on how many grapes they would sell to the winery. Meanwhile, someone maintained a record of crates to be filled with grapes the following day. The field was filled with dust and people were full of anticipation about the upcoming harvest.

Later, we moved to a coffee/tea house. There were around ten vignerons next to me. Among them was Ahmet, one of the oldest inhabitants of the village in his late 80s, who had been actively cultivating and transporting grapes to the factories for decades. There were also vignerons in their late 40s, 50s, and 60s. To learn about how grape prices were determined and how the privatization of TEKEL influenced grape cultivation, I asked if they remembered the first harvest after the state-owned wineries were dissolved. They proceeded to describe those initial sales after privatization. Although it was not a rehearsed narrative, they completed each other’s sentences.

In the early 2000s, before TEKEL was privatized, we sold our grapes for 35 kuruş—Turkish Lira cents [US$0.24]. [5] The following year, we [grape cultivators] met with one of the table wine [6] producers in the region in the village square. The wine producer crossed his legs and offered us 5 kuruş [US$0.03] less than the last year’s price. Most of us objected to the pricing since a raise would be given at the inflation rate during TEKEL. However, the winery owner underestimated our complaints and said this was his last offer. Referring to the grapes that would be harvested in the following days, he added: “Stop asking for a price on the day of a funeral. There is a corpse that we should clean first. No price is asked on the day of the funeral.” He talked about the grapes we worked and grew all year as corpses; he disrespected our labor to take advantage of the situation.

The frustration in their tone was evident. Although vignerons expressed their anger and heartbreak at the comments of the winery owner, some of them still trade with him as there are not many wineries in the market to buy vignerons’ grapes, especially after the privatization of TEKEL. With privatization, the supply and demand chain suddenly lost its balance. When TEKEL was the dominant producer, private wineries actively sought farmersto supply them with grapes. However, after the monopoly was dismantled, the situation reversed. Many grape cultivators struggled to find buyers or were offered inadequate prices. Regardless of how much they spent cultivating grapes, vignerons lacked bargaining power with alcohol producers. To avoid waste and to salvage their year-long labor, some sold their grapes for less than what TEKEL would have offered. Meanwhile, since the olive cooperative was still functional, certain vignerons expanded the number of olive trees and converted their vineyards into olive groves for a stable income.

In addition to uncertain grape pricing, the aging population in the village contributes to the presence of young olive trees in vineyards. Vignerons agree that cultivating grapes is physically more demanding than cultivating olives. Kemal has stated that the necessary labor requirements for olives is more predictable, with specific periods for pruning, spraying, and harvesting. In contrast, grape cultivation is more grueling, as vignerons must weed the couch grass after each rainfall and frequently apply sprays to protect grapes from diseases like Uncinula necator or Plasmopara viticola. Given the labor-intensive nature of grape cultivation and the aging population, the prevalence of olive trees in vineyards is peaking.

To sum up, even though grape cultivation is more profitable per unit, the economic stability that olives offer is one of the primary reasons behind the shift described in this article. Moreover, throughout my conversations with the vignerons, it was repeatedly emphasized that they represent the last generation tending to vineyards. Their children aspire to live in big cities. In essence, alongside issues related to prices and the challenges of finding buyers offering satisfactory prices, a significant predicament for Turkey’s rural population is the trend of young people seeking to establish their lives in city centers. With schools, hospitals, government offices, and socio-cultural activities predominantly concentrated in (large) cities, there is a move from rural areas to urban locales (Ribeiro, 2020). As vignerons often mentioned, the average age of working people in fields is over 40, signifying that this is the last generation engaged in grape cultivation. Simultaneously, a new agrarian class originating from Turkey’s cities has become involved in cultivating agricultural products such as wine grapes. Even though it is not the main focus of this article, I will provide a brief overview of viniculture in the next section to draw a better picture of the transformations unfolding in Turkey’s vineyards. [7]

In October 2017, the 56th edition of Cornucopia, self-described as the semiannual magazine for connoisseurs of Turkey, featured a special section on Turkish wines. Guided by renowned wine writer and critic Kevin Gould, journalists from the magazine visited various wineries across different regions of Turkey: “The road trip would start around Izmir—a city in the country’s Aegean coast—and meander tipsily north, turning right at Gallipoli before reaching Istanbul via Thrace” (Cornucopia, 2017, p. 56). Over the course of their journey, they not only sampled various bottles produced in different parts of Turkey, but also explored the country’s two wine trails and tasted wines of these localities: the Urla Wine Route and the Thrace Wine Route. With 35 years of experience in tasting Turkish wines and an extensive knowledge of the country’s wine history, Kevin Gould characterizes the current situation of the wine industry as Turkey’s wine renaissance.

Although ‘renaissance’ is an overly used term that does not specify who exactly is enjoying this rebirth, Turkey’s recent surge in the wine industry results from the growing number of wineries and vineyards explicitly dedicated to winemaking. These (mostly) small-scale and quality-oriented wineries, which I describe as postindustrial, are established by secular, globally connected, well-educated, and (upper)middle-class owners who reinvent themselves as post-industrial entrepreneurs (Ayaz, 2022). As a part of their quality-oriented philosophies, most post-industrial wineries view production as a complete, holistic process, beginning with cultivation of grapes in a vineyard and culminating in bottling the wine. As high-quality ingredients (in the case of wine, grapes) are a prerequisite for satisfying results (Simpson, 2011; Ulin, 1996), wineries aligned with the post-industrial mode of production—especially those committed to overseeing the entire process from vineyard to glass—begin their journeys by establishing vineyards. In other words, they become engaged in winemaking—viniculture—and in the sphere of grape cultivation—viticulture.

Following global trends, these wineries are either established in the same yard with vineyards—known as the French chateau production style—or located nearby. While winemaking during the TEKEL period was based on buying grapes from farmers, the new generation of wineries process the grapes from their own vineyards. With the rise of quality-oriented wineries in Turkey, grape cultivation has welcomed a new chapter in its history directly and explicitly oriented to winemaking.

Turkey’s interest in winemaking-oriented grape cultivation has been growing in recent years. There has been an increase in the number of producers in the country, now totaling almost 200. On the one hand, most of the wineries established after the privatization of TEKEL are expanding their vineyard area to diversify grape varietals and assume control over production from vineyard to glass. On the other hand, people who aspire to produce wine in the later stages of life have started buying vineyard areas. All these new investments have their imprints on wine-oriented viticulture. Statistics indicate a significant shift in grape distribution in recent years; 10.40% of Turkey’s total fresh grape production of 3,670,000 tons is used in winemaking (TURKSTAT, 2022), compared to only 3% in 2008 (Gümüş & Gümüş, 2008). An agronomist from Turkey once said, “Turkey is the land of old viticulture but new viniculture.” It is undeniable that TEKEL’s privatization has fueled an increase in the number of wine producers in the country.

The new form of small-scale and quality-oriented production emerged only in the late 1990s, blossoming in the first decade of the 2000s. To this end, the investment of elites is crucial for comprehending the changing ecologies of production that have enabled the transition from industrial to post-industrial modes. While the former prioritized volume, the latter primarily highlights the attributes of the final product. The transition from industrial to post-industrial signifies a shift from quantity to quality; in other words, a quality turn is happening in Turkey’s wineries. This does not imply that the wine produced in Turkey before was of low quality. However, ‘quality’ as an adjective was not a defining attribute of the production strategy.

Until the 1990s and early 2000s, with a few exceptions, Turkey’s wine industry was primarily divided into producing white or red wine. The phenolic attributes of grape varietals, the importance of soil features and cultivation techniques in flavor determination, and the roles of vinification tools and materials did not significantly influence most producers and consumers. Wine was often associated with alcoholism. As one of my interlocutors, Erkan Amca [8] , a man in his early 80s, told me when I met him in 2018, analyzing the sales trends of Coca-Cola in Turkey’s northwest would reveal much about wine consumption in the region. Due to generally undesirable taste and quality, mixing wine with Coke would make it palatable. [9] As such, şarapçı, a Turkish word describing wine producers and/or drinkers, carried a negative connotation for a long time.

However, in the late 1990s and early 2000s, the perception ofşarapçı in Turkey, or those drinking simply to get drunk, started to change. Urban individuals from the upper-middle classes and non-agricultural sectors, such as textiles, banking, and technology, began channeling a portion of their savings into grape cultivation and winemaking. Yet, it is not only the demographics of wine production participants that have changed. New connections have also formed with wine- and taste-oriented configurations within Turkey’s wine industry. In other words, distinct from quantity-oriented industrial wineries traditionally run by agricultural families for generations, these new producers prioritize the quality of their wine bottles. Their goal is to produce wines that encourage discussions about flavor profiles and pair well with various foods, rather than serving solely as inebriating beverages. These producers aspire to establish a respectable reputation for their wines and for Turkey within the global wine industry. This endeavor involves participation in international wine competitions, collaboration with renowned wine experts, and the establishment of state-of-the-art wineries. This article is the outcome of initial curiosity about who these individuals are and why they opted to become wine producers in Turkey, particularly in a climate of rising authoritarianism linked to the neo-liberal Islamist Justice and Development Party (Adalet ve Kalkınma Partisi—AKP), which has single-handedly ruled the country since 2002.

The Republic of Turkey, established in 1923, based its statist economy primarily on agricultural production in rural areas. Therefore, village economies have been essential for the statist republic (Örmecioğlu, 2019). However, the neo-liberal shifts that took root in Turkey’s economy during the 1980s redirected focus primarily toward urban areas. The former economic model supported rural areas by outsourcing their raw agricultural and husbandry materials (grapes, beetroot, and wool, to name a few) and turning them into final products in state-supported factories. The abolition of these factories and the implementation of various cycles of privatization have created a dependency for the agrarian class on private producers and their capital owners.

Çağlar Keyder and Zafer Yenal, scholars from Turkey who have worked extensively on the effects of neo-liberalization on the peasantry, assert that “government policies no longer have the power to control the developments in the agricultural sector and protect the villagers and small-scale producers against the market” (Keyder & Yenal, 2013, p. 39). For grape cultivators in Turkey, the absence of state-owned control mechanisms often adversely affects their incomes. On the one hand, the classical peasant class in the country deals with fluctuating prices. On the other hand, tending a field—vineyard or olive grove—is becoming increasingly expensive due to rising unit costs for essential equipment and tools.

As the core of the definition of the peasant, and of the political ecology approach, is access to land and family labor (Narotzky, 2016). Farming is losing its economic viability, especially for small-scale farmers lacking significant land holdings and whose offspring desire to live in urban areas. The government still offers some price support or input subsidy policies. However, as Keyder and Yenal argue, “…they are no more than an effective means of regulation, marginal contributions made just to put them in a slightly better position in the hands of the producer” (ibid., p. 39). As a result, predicting what will be produced and how it will be produced in villages beyond the current generation of farmers has grown more challenging. However, the current scenario in Turkish winemaking and grape cultivation suggests that urbanites will play a leading role in the country’s wine-oriented grape cultivation.

The statist economy, centered on the village and the villagers, has been replaced by a neo-liberal turn wherein urban individuals actively participate in quality-oriented production within villages. To put it differently, generating revenue from agriculture has become increasingly precarious for small-scale farmers belonging to the traditional peasant class. Their livelihoods are marked by uncertainty, anxiety, and risk (Molé, 9 There is a specific term in Turkish for low quality table wine: Köpek öldüren—dog-killer. Ayaz Grassroots – Journal of Political Ecology Vol. 31, 2024 9 2010). Thus, much like the young olive trees now frequently spotted in vineyards, Turkey’s peasantry is in the midst of a transition that poses an uncertain future for the country’s grape cultivation and vineyard areas.

[1] Atak Ayaz is a PhD Candidate at the Department of Anthropology and Sociology, the Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies, Geneva, Switzerland. Email: atak.ayaz@graduateinstitute.ch. Acknowledgements: I want to thank İlkim Karakuş, Dr. Meenakshi Ambujam, and Dr. Kenan Behzat Sharpe for reading the earlier versions of this article. Their comments and editing suggestions have been invaluable. I also thank Dr. Shaila Seshia Galvin for guiding me throughout my Ph.D journey, which created the basis for this text. Her recommendations and criticisms have been crucial in forming my ideas. Lastly, I am grateful for the constructive criticism and suggestions of the anonymous reviewer. Their suggestions helped me extend the scope of my article. Any errors are my own and should not tarnish the reputations of these esteemed persons.

[2] There is substantial academic work focusing on the reasons behind the population exchange between Turkey and Greece and its effects. The Ph.D. dissertation written by Sibel Karakoç (2022), which examines how exchanges have been instrumentalized to boost the newly founded Republic of Turkey’s economy through tobacco cultivation, interestingly shows the political economy behind one of the largest migrations into the country.

[3] The brand Marmarabirlik is an association of Agricultural Sales Cooperatives formed in 1954 by the olive cultivators in the Marmara region. The aforementioned olive agriculture sales cooperative was established in 1986. (https://en.marmarabirlik.com.tr/history (access date: 29/11/2022)

[4] Originally the French varietal Cinsault. As the result of Turkification, it became Şensu, meaning happy/jovial water.

[5] Exchange rates based on 2003 data, where 1 TRY = 0.694158 USD.

[6] Table wine as a term denotes two distinct meanings: a wine production style and a quality level showing marked in wine classification. For more information, see: https://sonomawinegarden.com/what-is-table-wine/

[7] In this article, I deliberately do not read the altering grape cultivation in Turkey as cultural loss. Given that the main scope is how neo-liberalization affected the peasantry, I underline how production and rural development changed with the annihilation of state-owned production houses. However, considering that Anatolia is a central point in the journey of domestication of grapes, grapevine has played a major role in people’s agricultural and socio-cultural activities throughout history. To learn more about the viticulture tradition in Turkey, see: https://viticulturestudies.org/abstract.php?lang=en&id=5

[8] Amca means paternal uncle in Turkish. It is used for elders to show respect.

[9] There is a specific term in Turkish for low quality table wine: Köpek öldüren—dog-killer.

Akdemir, U., & Candar, S. (2022). Regional economics of viticulture in Turkey in the period 1970. Viticulture Studies (VIS), 2(2), 55-71. http://doi.org/10.52001/vis.2022.11.55.71

Ayaz, A. (2022) In pursuit of quality and taste: Post-industrial entrepreneurs. In E. Liebow & J. C. McKenna (Eds.). Anthropology and Entrepreneurship: The current state of research and practice. Symposium Proceedings 2020-2021 (pp. 35-45). American Anthropological Association.

Besky, S., & Padwe, J. (2016). Placing plants in territory. Environment and Society, 7 (1), 9-28. https://doi.org/10.3167/ares.2016.070102

Blomley, N. (2007). Making private property: Enclosure, common right and the work of hedges. Rural History, 18 (1), 1-21. http://doi.org/10.1017/S0956793306001993

Candar, S., Uysal, T., Ayaz, A., Akdemir, U., Korkutal, İ., & Bahar, E. (2021). Viticulture tradition in Turkey. Viticulture Studies (VIS), 1(1), 39-54. https://doi.org/10.52001/vis.2021.5

De León, J. (2015). The land of open graves: Living and dying on the migrant trail. University of California Press.

Doğruel, F., & Doğruel, A. S. (2000). Osmanlı’dan günümüze Tekel [Tekel from the Ottoman Empire to present]. Türkiye Ekonomik ve Toplumsal Tarih Vakfı.

Griffin, C. (2008). Protest practice and (tree) cultures of conflict: Understanding the spaces of ‘tree maiming’ in eighteenth‐and early nineteenth‐century England. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 33(1), 91-108. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-5661.2007.00282.x

Gümüş, S. G., & Gümüş, A. H. (2008). The wine sector in Turkey: Survey on 42 wineries. Bulgarian Journal of Agricultural Science, 14 (6), 549-556.

Karakoç, S. (2022). The political economy of the Greco-Turkish population exchange: The settlement of the exchanges in Turkey 1923-1929. PhD dissertation. State University of New York at Binghamton.

Keyder, Ç., & Zafer, Y. (2013). Bildigimiz tarimin sonu: Küresel iktidar ve köylülük [The end of agriculture as we know it: Global power and peasantry]. İletişim Yayınları.

Medeiros Ribeiro, J. D. (2023). Peasantry and rural resistance in the 21st century Turkey: The case of ÇiftçiSen. PhD dissertation. Middle East Technical University. https://open.metu.edu.tr/handle/11511/101907

Molé, N. J. (2010). Precarious subjects: Anticipating neoliberalism in Northern Italy’s workplace. American Anthropologist, 112(1), 38-53. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1548-1433.2009.01195.x

Narotzky, S. (2016). Where have all the peasants gone? Annual Review of Anthropology, 45(1), 301-318. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-anthro-102215-100240

Örmecioğlu, H. T. (2019). Cumhuriyetin ilk yıllarında köycülük tartışmaları ve numune Köyler [The early republican debates on peasantism and the model villages].

Belleten, 83(297), 729-752. https://doi.org/10.37879/belleten.2019.729 Simpson, J. (2011). Creating wine: The emergence of a world industry, 1840-1914. Princeton University Press.

TURKSTAT, (2022). Turkish statistical institute, Bitkisel Uretim Istatistikleri [Crop Production Statistics]. http://www.tuik.gov.tr/ (Access date: 29/11/2022).

Ulin, R.C. (1996). Vintages and traditions: An ethnohistory of southwest France wine cooperatives. Smithsonian Institution Press.

Yanık, K. (2019). Likörden saraba votkadan rakıya: Tekel’in nesi kaldı? Damaklarda tadı kaldı [From Liquor to Wine, Vodka to Rakı: What is left of Tekel? Taste remans on the palate]. Oğlak Yayıncılık.

9 / December / 2025

By: Gina D'Alesandro

8 / November / 2025

By: Mariana Calcagni G

19 / September / 2025

By: Taylor Steelman

19 / September / 2025

By: Eva Navarro

14 / June / 2025

By: Sarah Steinegger, Nora Katharina Faltmann