April / 6 / 2024

By: Virendra Kumar [1]

Climate crises and other manifestations of environmental degradation are inextricably linked to the universalizing technoscientific paradigm underpinning capitalist industrialization and modernization. This study aimed to problematize the modern/colonial ontological dualism underpinning environmental crises and advocate the indigenous/Adivasi relational onto-epistemology as a different reality that questions the virtues of science, capitalism, and colonial narrative and its continuation in subjectivity and social relation in the modern state. Drawing from the new materialist insights of human and non-human imbrications and the framework of political ontology, this study further analyzed the Dongaria Kondh people’s political success in defending their relational way of worlding against Corporate driven extractivism even if the state perpetuates violence and takes development initiatives simultaneously in the mineral-rich eastern Indian province. While other political movements have succumbed to the combined corporate and state power, the Dongaria’s political struggle continues in different forms. Finally, this article makes the point that knowledge and insights born out of political struggle against a particular ontology masquerading as universal press the need for engagement between different realities, knowledges, and recognition of a pluriverse, a world of multiple ways of worlding, where each ontological story exists not as superior or inferior, but as equal, with space for mutual engagement and dialogue.

political ontology, worlding, betweenness, relational cosmology, mass worship, state violence, collective well-being, engagement, interdependence.

Coloniality encompasses both the material reality of colonization and its immaterial, ideational, and ideological aspects in consciousness and thinking that permeate social relations, culture, mentalities, and subjectivities (Adelman, 2015). As such, the idea of coloniality is founded on dualistic epistemology that celebrates the virtues of science and capitalism. Climate coloniality as an analytical concept interrogates the hierarchical power relations established during active colonialism and its continuity in post-colonial space times (Sultana, 2022). As an idea, it questions the connection between the Eurocentric epistemologies of mastery, science and capitalism, and unequal climate change impacts in the global South, including the continued ecological destruction that has caused the dispossessions and impoverishment of many indigenous and local communities. In its pursuit of universalizing Western values, climate coloniality seeks to subalternize non-Western ways of being, seeing, and knowing. Can the underlying epistemological assumptions underpinning climate coloniality be challenged? What are the alternative onto-epistemology systems for saving the Earth and preventing extreme climate change in various forms and manifestations in the long run?

An alternative lens to colonial mentalities comes from indigenous and local tribal communities inhabiting specific local ecosystems. Rooted in the practices and experiences of several generations, indigenous epistemology is viewed as a “way of being/worlding” that is informed by an overlapping connection between cosmic worldviews and shared community life that accords values to the non-human world.

In this article, part I lays down the theoretical framework of new materialism and decolonial indigenous perspectives aimed at unsettling the dualistic epistemology underpinning modernity and coloniality. The new materialist “ontology of becoming and movement” and “human-non-human manifold entanglements” are combined with the decolonial conceptual lens of “border thinking” to delve deep into “differently rational” interwoven indigenous lifeworld practices that oscillate between dualistic ends. Part II examines colonialism, science, and Adivasi/tribal identity in the Indian context and how the ‘Adivasi’ political ontology, which lies in-between, has been challenging colonialism and agents of colonization in post-independence India. With this background of the Adivasi discourse, part III dwells on the interwoven lifeworld practices of Dongria Kondhs, who believe in the interdependence of all beings. The fourth part sheds light on the Dongaria’s defense of their relational world/lifeworld practices through continuous resistance to the overt and covert manoeuvers of Vedanta Aluminum Ltd to extract bauxite from the deeply revered Niyamgiri Mountain. The continued political defense of the “sacred” mountain against the state’s violence and benign development narratives has been analyzed from a comparative perspective. The final section brings together insights and knowledge born out of the Dongaria’s political struggle and Latin American indigenous people’s struggles against extractivism and the great ontological divide. These political struggles bring to the fore the idea of intertwining of being and knowing, interdependence of humans and non-humans and a pluriverse where each onto-epistemology exists as an equal, with space for mutual engagement to prevent ecological destruction and the consequent climate crisis that threatens both a prosperous and a less well-off world equally.

This article draws on indigenous methodologies/decolonizing methodologies, combining secondary data from research articles with primary qualitative data gathered from semi-structured in-depth interviews and participant observation-based field work. Indigenous/decolonial methodologies take a more self-reflexive approach in engaging with the relational ontologies and epistemologies of indigenous and Adivasi/tribal communities (Smith, 1999; Tripura, 2023). In transcending subject/object or knowing/being distinction, indigenous methodologies aim to privilege indigenous voices and epistemology (Kovach, 2010) and view the intertwining of knowing, being, and doing (Martin & Miraboopa, 2003).

As regards the disclosure of the researcher’s “positionality” (Kapoor, 2004), I studied political science at the University of Delhi, India, before joining the same to teach. As an observer and participant in various subaltern and social justice movements in India, I have kept myself updated about the Dongaria Kondh’s resistance against mining corporations since 2008. This awareness, together with academic colleagues with socialist leanings, helped me gain access to some prominent activists associated with the Niyamgiri movement. This in turn helped me obtain access to some Adivasi villages in the Niyamgiri hills.

I visited ten to twelve Dongaria Kondh villages inside the Niyamgiri chain of hills bound by the Rayagada and Kalahandi districts in October 2022 and September 2023. Apart from observing Dongaria Kondhs everyday life and their relationship with the place, I conducted six in-depth unstructured oral history interviews (Thompson, 2006) and engaged a few interviewees in conversational methods (Kovach, 2010; Tripura, 2023) to know their experiential knowledge that was handed down from generation to generation. Three Odiya activists who knew Hindi, Odiya, and the Kui language (spoken by the Dongaria Kondh) participated in the interviews as interpreters. One of them belonged to Kutia Kondh, living at the foothills, while the other two were from a farming community in other parts of the Kalahandi district. Most interviews/conversations lasted 2 to 3 hours. I also interviewed six activists associated with Niyamgiri Suraksha Samiti (NSS) in Muniguda and Kalahandi who had participated in a protest rally in Bhawaniatna, the district capital of Kalahandi, in October 2022. Activists cum interpreters also made available various YouTube videos in the local language that showed the Dongarias’ mass worship of Niyamgiri Mountain every year. I also interviewed the heads of a few nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) who worked for the betterment of the Dongarias.

A few official reports and data were also gathered from institutional websites to testify to the reference made by activists regarding the government’s coercive measures to weaken the Dongarias’ collective mobilization to protect their sacred hill. Most fieldwork data were analyzed around the Dongarias’ political onto-epistemology. They were quoted directly in some places and paraphrased in other places in major sections of the article. All the mandatory ethical protocols, including the interviewees’ anonymity, were maintained.

This article draws on a new materialist political ecology paradigm and decolonial thinking, synthesizes these perspectives to question assumptions underpinning capitalist modernity, and examines the indigenous/Adivasi onto-epistemology and its political implications. Despite the diverse scholarly positions, new materialist political ecologists reject the Cartesian dualism intrinsic to modernity: matter/spirit, nature/culture, and human/non-human. Scholars associated with science and technology studies have unsettled the ever-expanding dualism on the basis of the modern ontological great divide between nature and culture or object and subject, and proposes a flat ontology in which performance preceded entities (Blaser, 2010; Latour, 1993). Unlike post-structuralism, which undertakes a linguistic or textual deconstruction of oppositions, they insist upon “irreducible imbrications of human/non-human system or natural /social process” (Coole, 2013, p. 454). From this perspective, humans are not exceptional in having agency and rationality, and these terms, such as self-consciousness, rationality, and cognition, are reified abstractions that omit manifold and intricate non-human processes. Therefore, new materialist ontology decenters humans and focuses on how relational networks or animate and inanimate assemblages affect and are affected (DeLanda, 2006, as cited in Fox & Alldred, 2015). From this perspective, “the manifold interaction between human and non-human processes goes on and on, ceaselessly generating new form”(Bennett, 2001, p. 165). New materialists understand materiality in a relational and emergent sense (Coole & Frost, 2010) and focus on processes and interactions (Deleuze & Guattari,1984, as cited in Fox & Alldred, 2015). Drawing from the Deleuzian philosophy, science and technology studies, and some versions of phenomenology, new materialists thus delineate a “picture of socio-material worlds as always-emergent heterogeneous assemblages of human and more-than-human”(Blaser, 2012, p. 50).

The decolonial paradigm strives to delink knowledge from Western-centric epistemologies that silence non-Western voices, knowledge, and languages within a totalizing hierarchy of a single modernity (Mignolo, 2007). Thus, an alternative epistemology to the “totality of Western epistemology” presupposes “border thinking” that connects diverse local histories and subjectivities subjected to colonial wounds and imperial subordination (Mignolo, 2007, p. 493). Border thinking is thinking in exteriority, in spaces and time, that the self-narrative of modernity invented as its “outside” to legitimize its own logic of coloniality. As such, this process involves violence and coercion in the subalternization of non-Western voices (Mignolo, 2011). “Border epistemology is thus thinking outside the epistemic and ontological borders of the modern/colonial world, not the borders of the national state” (Mignolo, 2011, p. 277). By speaking of “colonial difference” and “delinking from modern rationality” (Mignolo, 2007, p. 498), the border thinking framework brings to the fore the “power dimension” that is often lost in the relativistic account of “cultural difference” (Escobar, 2007b, p. 189). With the “ontological turn in social theory” (Escobar, 2007a, p. 1), the category of ontology, as a way of worlding, seeks to replace “culture,” as the notion of “cultural difference” is associated with the modern ontological assumption that there is only one reality or world and that there are multiple perspectives or representations of it (Blaser, 2012, p. 52). Thus treating “difference” as cultural, we advance a particular ontology, which does not do justice with ontological differences, as there are multiple realities or worlds (Blaser, 2012, p. 52).

The framework of political ontology (Blaser, 2010), drawing from the intersection between indigenous studies and science and technology studies with momentous developments in socio-natural life such as Latin American indigenous uprisings and struggles (Escobar, 2016, p. 21), “operates on presumptions of divergent worldings coming about through negotiations, enmeshments, crossings and interruptions” (De la Cadena & Blaser, 2018, p. 6). The idea of political ontology fully recognizes the existence of “other worlds”—not cultures—that are “different” from the modern world and that “different ways of worldings” also get enacted/performed with reference to “their world making effects” (Blaser,2012, p. 54).Thus, unlike other modalities of analysis, political ontology is not concerned with a supposedly external and independent reality; rather, it is concerned with “reality making,” including its own participation in reality making, apart from opening up space for engagement of different ontological positions, without subalternizing anyone, and thus enact a pluriverse (Blaser, 2013, p. 552). It even encompasses “culture,” which, as an analytical category, limits our capacity to recognize other ontologies in their own terms (Blaser, 2009, p. 890). Thus, political ontology, being part of the “ontological turn” in social theory, seeks to understand as to how different ways of wording can sustain themselves even as they interact, interfere, and mingle with each other (Blaser, 2013, p. 552).

The Adivasi/tribal communities in India pursue lifeworld practices that constitute a different relational onto epistemology. This alternative mode of being and knowing stands in tension with colonial/modern ontology and epistemology that sees the non-human world, separate from the human world, as a source of resource appropriation. The next section will shed more light on the complex Adivasi/tribal discourse in post-independence India and reflect on their peculiar position of “betweenness” in colonial and post-colonial discourse.

The ideas of “tribe” and “Adivasi” are conflated and confused. The colonial state defined “tribe” essentially in terms of fixed and identifiable characteristics distinguished from the institution of “caste” and other organized religions such as Hinduism, Islam, and Christianity (Roycraft & Dasgupta, 2011, pp. 3–4). Whereas imperial officers and ethnographers have presented themselves as “men of science, academia and civilization,” “tribes/Adivasis” have been portrayed as primitive people who lacked scientific spirit and civilized culture. Even as the nature of “otherness” varied according to changing binaries such as forest dwellers compared with plain people and animists compared with polytheists, the “tribe” typified geographical, cultural, and economic “separateness” and hence resonated with notions of “the primitive” (Roycraft & Dasgupta, 2011, p. 4). This portrayal of tribes as forest-dwelling animistic people who use primitive technology is a colonial narrative premised on a binary wherein science and reason were accorded a superior position in comparison with culture and nature.

Against this backdrop, Indian scholarship has employed the trope of “Adivasi” instead of “indigenous communities” to contest modernity since the 1980s (Banerjee, 2006, p. 32). In the Indian context, “Adivasis” is considered a local community living largely in forested areas with its own political agency during the colonial era, as in post-independent India. They are also called “scheduled tribes,” who are entitled to government affirmative action measures in official documents. For the purpose of this study, Adivasis remains a more relevant political category.

Colonial ethnological accounts depict Adivasis as an essentially cohesive community that was absent in mainstream caste society and represented a culture of subversive and marginal politics, which is not quite shared by mainstream Indian society. They became a “critical alterity” to the Indian state, as it became evident that the development of modern India meant meeting most of India’s timber and mineral resources from exhausting tribal forest lands (Banerjee, 2006, pp. 102–105). Prathama Banerjee also pointed out that a “culturalist” lens to approach Adivasi/tribals has been strengthened by the emergence of environmental discourse in India (Krishnan & Naga, 2017, p. 5). They cast the colonizer, market, and state as agents of ecological destruction and Adivasis as “nature’s conservators” (Krishnan & Naga, 2017). Traditional Adivasi communities, who are a subgroup of subaltern ecosystem people, were natural conservationists who lived in socially harmonious and environmentally sustainable ways and believed that the golden age was destroyed with the onslaught of colonialism, science, and development (Gadgil & Guha, 1993).

Vandana Shiva drew attention to ecological destruction and crisis in corporate-driven developments within the limits of the market economy and how its cost is borne by local Adivasi communities who participate in the survival economy of the same land, thus creating new forms of poverty and dispossession (Bandyopadhyay & Shiva, 1988).

This position, though taken by subaltern scholars and activists who support resistance movements against development projects, has attracted critical anthropological studies. Their works challenge the essentialist Adivasi culture that has remained the same and fixed forever at a low evolutionary state and believe that Adivasis in India exhibit variations in lifestyles, languages, and religion, therefore making strict comparison with international indigenous discourse challenging (Shah, 2007, as cited in Oskarsson, 2017).

The Indian state has sought to legally define tribal communities and grant certain legal rights such as forest rights and other welfare provisions, therefore, Adivasis are expected to integrate into modern government. At the same time, they are expected to be “tribal” (by state classification and by the fact of their dependence on forest for subsistence needs). While identity performance through ceremonies and rituals and ways of being are critical to the Adivasi encounter with Indian legal apparatus in the context of mining and looming dispossession, they may also generate certain uneasiness by simultaneously pulling people toward and against ideas of modernity (Nielson & Oskarsson, 2017; Ramesh, 2017).

Under the constitution of India, tribal communities are entitled to live their collective life while representing the “borderline” condition of temporal disjunct; it is both inside and outside the logic of nation state, market, and capital (Dastidar, 2016). Owing to their “collective agency”, this typical temporal “in-betweenness” makes them differ from groups that speak in the name of progressive projects of the nation (Bhabha, 1997, as cited in Dastidar, 2016). Whereas the Indian state champions industrial development and growth based on harnessing mineral and other natural resources, Indian environmentalists point to the “dispossession” and “displacement” of Adivasi and other land-dependent communities (Guha, 2007). In the post-1990s liberalization era, as the Indian state allowed private capital to access its regions with mineral resources in the name of market access, it entailed disciplining the “subaltern” who are “presented as inhabiting a series of local spaces across globe that marked by label social exclusion lie outside the normal civil society…their route back…is through willing and active transformation of themselves to conform to the discipline of the market” (Cameron & Palan, 2004, p. 148 in Kapoor, 2011).

Gayatri Spivak raised a fundamental question about representing these global south subaltern voices by international and local activists whose intellectual horizons are imbued with Western rationalistic ethos (Borde, 2017): “Can subaltern speak?”. It is this messy and contested world of scientific rationality underpinning the universalizing extractive developmentalism, nation-state, and existence of the Adivasi community’s relational way of worlding challenging universalizing colonial modernity that forms the backdrop on which to reflect Dongaria Kondh politico-onto-epistemology.

Relational ontology conceives of the world as ongoing processes of relations and interconnections. Sentient or insentient, and organic or inorganic entities are not objects. Rather, they are in motion. According to anthropologist Tim Ingold (2011),”the relational world is a world in movement, flux and becoming. There is continuous formation and transformation through the interplay of wind, water, and stone…within a field of cosmic forces” (p. 131). Furthermore, he explained that” beings not simply occupy the world, they inhabit it. And in so doing—in threading their own paths through meshwork—they contribute to its ever-evolving weave” (Ingold, 2011, p. 71). The Dongaria Kondh onto-epistemology also contributes to this ever-evolving weave.

The Dongaria Kondh community, an Adivasi community that has inhabited the Niyamgiri hill tracts of the Rayagada and Kalahandi districts of Southern Odisha, India, for centuries, leads a life intertwined with a more-than-human world.[1] This deeply forested chain of hills, stretching over 200 square kilometers, is biodiversity rich with thousands of plant species and numerous local streams and springs dissecting the hilly landscape.[2] As I, along with interpreters, entered the deep forest from the Munniguda block (Rayagada district) and walked along the narrow path, I was amazed by the sublime beauty of the lofty hills covered by dense forests and the gushing sound of local streams. Daitree, who belonged to the Kutia Kondh community at the foothills, accompanied me as my interpreter and explained the web of such streams feeding the entire assemblage of plants, people, animals, and various crops on hills and plains:

There are over thirty such local streams flowing through these Niyamgiri range of hills, which combine together to form two major rivers, Vasamdhara and Nagavali, that provide water for drinking and irrigation in downstream areas, thus supporting the ecology and livelihood of a large population, other than roughly 8,000 Dongaria Kondh living on the hills.

This large assemblage itself encompasses both animate and inanimate non-human entities such as forests, streams, and hills, not as isolated components but as deeply enmeshed components in ongoing interactive processes that have existed for centuries, much before human groups such as the Dongaria Kondh and their oldest member can recall the time of their ancestors’ settlement in these rugged terrains. The Dongaria community practices swidden cultivation on hill slopes owned by the entire village community/clan. By and large, they practice a subsistence economy. This communal ownership has been for generations and, as such, does not require any article or document. Whatever they grow on these hill slopes—millets, fruits, and spices, among others—are taken to be blessings of their ancestral god, Niyam Raja (King of Law) and Dharni Pennu (Mother Earth).

Lado Sikka, a community leader from the village of Lakh Padar, described the relational world as follows: “From generation to generation, hills, mountains, forests, water, and Earth belong to us, and we belong to them. There is no life without them.” Thus, the Dongaria life is intertwined with the non-human world in a way that an inseparable relation with the non-human world defines existence, not the other way around. Every Dongaria Kondh reveres the top hill forest (Trunjelimuneri) of the Niyamgiri Mountain (in Lanjigarh, Kalahandi, of triangular shape, stretching over 4000 meters) as the abode of their god, Niyam Raja. Therefore, they regard the top hill forest as “sacred” and follow traditions and regulations prescribing appropriate behavior for the members of Dongaria society. They do not cut trees for any individual or common purposes.

Behind these moral restraints lie oral stories, legends, myths, and chants that link the Dongaria origin and existence to Dharma Devta (Deity of Religion), who is believed to have sent Niyam Raja on Earth; that Niyam Raja is the creator of hills and the different varieties of plant species; and that he became king of the hill gods and chose the highest peak as his abode, Niyam Dongar, from where he could observe his people. Being preoccupied with the people’s welfare, he would receive a part of the yields of those who tilled the soil in his kingdom as ritual offerings (Jena et al., 2002). The Niyam Raja, a mythical god-king of hills, thus constitutes a spiritual/supra-world that connects complex assemblages of non-human realms involving sentient and non-sentient beings such as plants, animals, hills, streams, and winds with the human world. For Dongarias, connecting with the earth, sky, streams, hills, forest, rains, wind, sun, moon, stars, lineage, and cereals (LahiPennu) is a “way of worlding” and “existence,” and each one attracts some sort of reverence, respect, and reciprocity devoid of utilitarian calculations. This spiritual relationality with “more than human world” finds expression in cultural celebrations and ritual observance such as Miriaparab/Niyam Rajaparab (festival), worshiping Dharni Pennu (Earth Goddess) and other deities.

Rupuli Majhi, an elderly woman from the village of Phuldhumbe, narrated the relational way of worlding during the interaction: “There is jeev (soul) in every being and life form. We (Dongaria Kondhs) respect every soul (jeev)…We worship jangal, jameen, dongar, parvat, jharna, Pashu, Pakshi (forest, land, hills, mountains, springs, animals, birds). Dongaria’s existence is unthinkable without worshipping Niyam Raja and Dharni Pennu. For Dharani Pennu (Earth Goddess), a shrine is dedicated to each village (Borde & Bluemling, 2021). After every new harvest, they offer food grains to Dharani Pennu before personal use.

Samya Wadka, one of the elders from the village of Khajuri, described the relation of humility, reciprocity, and reverence with Earth: “We owe our existence to Dharni Pennu. We worship her. Whatever we produce—from varieties of millets such as khosla, kandul, mandyas to fruits, spices, and oilseeds—belongs to Mother Earth.” The mountain god and other deities cannot be seen by human beings, but they may be summoned by ritual specialists, priests, and shamans who represent gods and deities by going into a trance. When summoned, the gods leave their homes, visit human hosts, and then return (Hardenberg, 2016).

Thus, in Dongaria Kondh onto-epistemology, nature, with all its or sentient and insentient materiality, spirituality, and culture, and rituals and observances, is inseparable and constitute a way of worlding/cosmology that oscillates between dualistic ends: rational/irrational, traditional/modern, and matter/spirit. In such non-Western cosmologies, the sensory world, according to Henry Corbin, is mediated through the imaginative function of the “spirit” and “sacred” world. This imagined world is not simply utopian fantasy; instead, it is a realm of being rooted in both the cognitive and cosmological function of the imagination (Corbin, 1972). In other words, cognitive rationality is mediated by imaginative faculty to find meaning in relation to the “realm of spirit and sacred,” thereby enacting a “different” onto-story, escaping the dilemma of current rationalism, which leaves a choice between two terms of banal dualism: either matter or spirit. There is coming and going between the human, non-human, and spiritual worlds (Restrepo, 1996, as cited in Escobar, 2015). Through cultural practices, sounds, and chants, they interact with the noumenal/sacred world and reaffirm their manifold connection/entanglement with the latter.

Jane Bennett, representing a materialist-spiritualist intellectual tradition, drawing on Deleuze and Guattari’s conceptualization of cosmos as “energetic aspects of things, thoughts, matters …forces, densities … not thinkable in themselves, “maintained that “repetitive sounds like chants and refrains provide sensory access into the cosmological dimension of things” (Bennett, 2001, p. 166). Thus, enchantment is a feeling of being connected in an affirmative way to existence (Bennett, 2001). The Dongaria’s way of worlding, in advocating deeper connection with the cosmos that evokes reverence, humility, and reciprocity, thus inspire ecological wisdom to resist unjust modes of commercialization. Although they make daily livelihood from forest and forest resources, including fuel and even selling small wood logs in nearby local markets, they do so in a way that does not harm the local ecosystem.[3] Thus, everyday material practices do not contradict their onto-epistemology, which sees Dharni Pennu (Mother Earth) as the life giver to all beings and therefore as sacred. The preservation of their community life, with all its celebrations, myths, and tales of enchantment, and their local ecosystem is bound with the earth’s existence, with all its life forms and materiality. Does the Dongaria’s way of worlding obtain a political expression in defending their relational cosmology and challenge a particular ontology, masquerading as “universal,” of individuals and markets (the one-world world) that attempts to transform all other worlds into one (Escobar, 2016, p. 20).

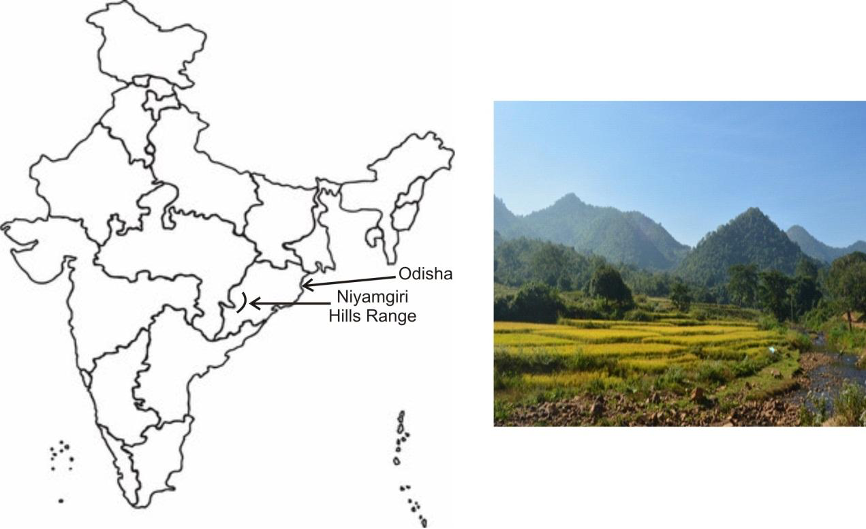

Figure 1: The political map of India, with a special focus Figure 2: Glimpse of Niyamgiri Hills. on Odisha, where Niyamgiri Hills is located.

Source: vikalpsangam.org/article/glimpse of Niyamgiri Hills

The Dongaria Kondhs’ political defense of their relational word against the combined might of transnational corporations and the state spanned over two decades, witnessed violence, torture, and even allurements of all sorts. The Dongarias’ way of worlding came under attack from Vedanta Aluminum Ltd, a London-based Mining Corporation, in the early 2000s. Thus, there started a political movement involving the Dongaria Kondhs, non-Dongaria subaltern communities living in plains; activist academicians; and various Marxist organizations who supported the relational lifeworld as a critical alterity against universalizing capitalist modernity in guise of “developmentalism”. Local protests and oppositions began in the early 2000s, as it became public that London-based Vedanta Aluminum Ltd. would mine the Niyamgiri hills to extract bauxite and that an aluminum refinery plant would be set up at Lanjigarh, Kalahandi.

While local organizations such as the NSS and Kalahandi Sacheta Nagrik Manch mobilized the Dongarias and local people at grass root levels and faced state repression, many activists and organizations filed litigations in the Supreme Court of India on grounds of destruction of ecology and biodiversity (Kumar, 2013).[4] The movement had a setback, as the Supreme Court ruling (2008) allowed mining projects with certain conditions. This heavy blow led the host of local and national organizations and international nongovernmental organizations to politicize rather dispersed and village-level ritual tributes to Niyam Raja, whose spirit is believed to reside in the Niyamgiri Mountain, located very close to Lanjigarh (Kalahandi district), where the aluminum refinery was built. Thus, mass worship ceremonies were started on the top of the Niyamgiri Mountain, Hundaljali, the mining site for bauxite extraction, even as the anti-Vedanta movement saw tensions and ruptures between foreign NGOs and local and national Marxist political organizations (Kraemer et al., 2013, as cited in Borde, 2021). This “mass worshiping” was a political performance to defend not just a specific mountain that was to be mined by Vedanta Ltd., but also the entire Niyamgiri chain of hills. Thus, the political expression of “sacred belief” and “indigeneity” was made public to show the organic connection to nature as against nature devouring corporate extraction and consequent ecological destruction and displacement of the Dongarias (Krishnan & Naga, 2017, p. 11).

The continuing political struggles, together with the efforts to utilize the Forest Right Act, 2006, finally culminated in the landmark Supreme Court judgment (2013) that empowered the Dongaria community to decide whether mining should be allowed on the Niyamgiri.[5] All the concerned village assemblies unanimously rejected the proposed bauxite mining by Vedanta and claimed that the “entire Niyamgiri range of hills as sacred and not just specific site of mining, Hundaljali, at Niyamgiri Mountain” (Borde & Bluemling, 2021, p. 82) and that we “do not need any individual land ownership from the government; we need Niyamgiri only” (Jena, 2013, p. 15). Therefore, the Indian Ministry of Environment and Forest banned the mining project on the Niyamgiri Mountain in 2014, but it did not extend to the entire Niyamgiri range of hills.

Therefore, the Dongarias’ claim to the entire Niyamgiri range of hills as “sacred” remains verbal. In fact, the Dongaria Kondhs and other Kondh communities and farmers living in and around the Niyamgiri hills strongly believe that unless the aluminum refinery does not get closed permanently, threat to their sacred mountain and Dongarian life will persist. In this context, the mass worship of their hill god, Niyam Raja, on top of Niyamgiri Mountain every year is a covert form of political strategy against the combined might of Vedanta Corporation and the Odisha government. Over the years, this mass worshiping, which is held in February every year, has seen increasing participation of common people from Odisha, activists, and organizations across India. According to activist Lingraj Anand, who is associated with the NSS, “many local nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) and activists attend Niyam Raja Parab (mass worshiping of Niyam Raja) every year in February. The increasing participation of non-Dongaria activists and common people boost our morale to fight corporate drive to take over Niyamgiri in guise of development.” Thus, civil society members and activists are standing with Dongaria’s way of worlding against any future possibility of allowing bauxite mining. Activists have mentioned that not many movements have been successful in resisting the takeover of hills by corporations. Lalin Kumar, an activist from Kalahandi, stated that the

Kashipur movement, which continued for twenty-one years, could not stop Utkal alumina project, a subsidiary of Aditya Birla Group Hindalco, to secure around 200 million tons of bauxite from the Baphli Hills in Rayagada. The Jagatsinghpur movement also proved weak to stop the POSCO steel project, and there are other cases as well in this mineral-rich state.

Recently, Sigmali Hill, located a few kilometers away from Niyamgiri Hills, has been auctioned by the Odisha government to mine and supply bauxite to Lanjigarh refinery” (Barik, 2023). These concerns are strengthened by the Odisha police’s increasing use of intimidation, surveillance, and arrest of Dongarias and non-Dongarias activists associated with NSS on false charges of being Maoists. These cases have been documented by the fact-finding committee of the People’s Union for Civil and Democratic Rights (PUDR) and the Communist Party of India Marxist-Leninist (CPI-ML). In the post-Supreme Court landmark judgment (2013) period that banned mining in Niyamgiri Mountain, there emerged overt and covert cases of state violence on a regular basis, which were meant to prevent the holding of public meetings and rallies. Needless to say, the number and frequency of protests and rallies have decreased significantly, especially after the COVID-19 outbreak in 2020.

Parallel to the increasing state surveillance and violence against activists, the Dongaria’s relational worlding also negotiates with the modernist development narrative. Vedanta Corporation claims to support schools, agandwadi (primary child development center), and hospitals in the Lanjigarh area, where the refinery is located, under corporate social responsibility (Kraemer et al., 2013). Local staffs, employed in these institutions, appreciate the Vedanta initiatives, though activists see it as mask for corporate plunder of minerals and destruction of ecology forever. The Odisha government too, with its decentralized local institutions and dedicated development agencies such as DKDA and OPELIP, aims to provide welfare measures and uplift the Dongarias’ socioeconomic status, although these measures are implemented half-heartedly and haphazardly (Tatpati et al., 2018).[6] Activist Angad from Kalahandi provided a critical account of these development initiatives: “Most of the schools run by government do not impart education in local Kui language, which is easily understandable by Dongaria kids. In the deep forest, there are no school buildings or hospitals.” One coordinator associated with the NGO named Adivasi Kalyan Parisad (Council of Adivasis’ Welfare) based in Rayagada also pointed out that “bureaucrats handling OPELIP are more concerned with cornering commissions/bribes in the name of development of Dongaria and that involving local NGO in the development task is mere tokenism.”

On ground, very little has been done for the Dongarias. Field observations tell us that few things like solar panels and water tanks in the few visited villages are visible. I am told that they also receive rice from the public distribution system managed by local self-governance institutions. Thus, the Dongaria’s way of worlding interacts with local self-governance institutions and bureaucratic agencies entrusted with development. Can these welfare measures be seen as an unnecessary interference into the Dongarias’ relational cosmology? To the extent that these measures do not break the organic connection with broader ecology and do not lead to the dispossession of Adivasis, they can be taken in a positive way to better their material condition, although such welfare-centric development must be tailored to hear more local voices at the bottom at a specific place than being only expert driven. However, there is a modernist economic growth model based on nature-culture ontological separation that determines the state’s economic policies towards hills and forests and the broader non-human world.

However, this colonial capitalist growth model builds on the universal applicability of science and profitability value in mineral extraction (Oskarsson, 2017). Minerals are considered vital inputs in industrial processes or as providing crucial export revenues, which are keys to technical and economic progress (Lahiri-Dutt, 2016, as cited in Nielson & Oskarsson, 2017). Many Odiya youth, especially the so-called urban educated, subscribe to this modernist position that development involves sacrifice of nature to some extent and that large corporate investment in the “backward regions” brings employment and poverty alleviation. This typical rosy picture fails to see that in many cases, such extractivism-driven development has actively “dispossessed” many Adivasis of their traditional means of life and livelihood, apart from causing havoc to ecology in multiple ways. In fact, the Indian environmentalist Ramchandra Guha maintains that in post-independent India, the Adivasis of central and eastern India who live in mineral-rich regions had to make way for commercial forestry, dams, and mines in the name of economic and industrial development (Guha, 2007) and that universalizing science and technical experts are to engage with place-based indigenous knowledge practices and experiences (Gadgil & Guha, 1993).

The ideology of development involves violence against those cultural communities who do not subscribe to universalizing homogenized mass consumption, therefore, struggle against developmentalism is a struggle for reclaiming the dignity of culture waiting to be sacrificed (Nandy, 1994). Despite the constitutional and legal protection under the Forest Right Act, 2006, and PESA (Panchayati raj/local self-governance institution extension to scheduled areas 1996), which grants rights to village communities/forest-dwelling community to decide the use and regulation of local forest resources, Adivasi communities such as the Dongarias face threat of dispossession and displacement due to the tacit collusion between the state and the capital. Therefore, the political struggle of Dongaria Kondhs continues in defense of relational and interwoven ways of being, knowing, and doing.

The Dongaria’s political struggle to protect the “sacred Niyamgiri hill” finds parallel in Andes indigenous movements in Bolivia, Peru, and Ecuador to protect the human non-human relational world. These Indigenous communities see mountains such as Ausangate or Quilish as “earth beings” or sentient beings threatened by the neoliberal wedding between the capital and the state (De la Cadena, 2010, p. 342). By politicizing the affective interaction with other-than-human, earth beings, Andean indigenous movements seek to dispute the monopoly of science to define “nature” and thus provincializing the alleged universal ontology of the West as one world in a pluriverse (De la Cadena, 2010, p. 346). These movements went on to push for the recognition of pachamama (Mother Nature) as a subject with rights in the new constitution that emerged from the struggles in the mid-2000s. This constitutional recognition of the rights of nature and the idea of good living or collective well-being (buen vivir in Spanish) that flows from it have emerged as alternative life projects to those offered by development and progress (Blaser, 2013). Buen vivir as a notion of collective well-being that grew out of indigenous struggles in South America represents a different philosophy of life that subordinates economic objectives to interlinked criteria of ecology, human dignity, and social justice (Escobar, 2016).

Although the Dongaria Kondh’s political struggle did not lead to a similar categorical concrete constitutional recognition of earth beings with rights, it advanced an idea of well-being that is in harmony with nature, with all its spiritual energy and perpetual connections. In defending the specific sacred Niyamgiri hill, which stretches over roughly 4000 meters, they went on to claim the entire chain of hills as sacred and therefore “extraction” in the name of “development” would amount to destroying manifold entanglements between human, non-human and cosmic world. Thus, the Niyamgiri movement privileges ecological and social interdependence over pure economic rationality. That the government of the day has not legally banned mining on the entire range of hills is the reason that they vow to fight till death. No material inducements such as government jobs and even government welfare measures have shaken their resolve to defend their relational way of worlding, even if they are seen as poor and backward in modern “development” discourse.

Both the Andean indigenous movements and Dongaria Kondh’s political resistance against the capital and state bring to the fore a “different reality,” even as multiple ways of being, knowing, and doing have been subalternized through relentless processes of expansion and colonization that also involve a great deal of violence and coercion (Mignolo, 2007; Blaser, 2010). Both the Dongaria’s political movement and Latin American indigenous movements, though thousands of miles apart, have established the idea of ontological and epistemological pluralism and the coexistence of many ways of worlding without dominating each other. The engagement and dialogue between the different ontological positions and ways of worlding have become more important, as universal ontological assumptions are seen as underpinning factors behind the contemporary ecological and climate crisis (Escobar, 2015; Pandelton-Julian & Brown, 2023). This ever intensification of the climate crisis, threatening both modern and pre-modern societies, cannot be addressed by more capitalism and “totalizing” rationality (de Sousa Santos, 2014).

While climate coloniality manifests through capitalist extractivism and technoscience, the idea of “collective well-being” as deeply connected to the “sacred hill/living hill” constitutes epistemic disobedience to coloniality/modernity. To see a non-sentient entity such as a hill as a “living spirit” that evokes awe, respect, and restraint is to engage with a different cosmovision that challenges science and development experts’ monopoly to represent nature. Science, to turn the world into an object of concern, places itself above and beyond the very world it claims to understand (Ingold, 2011). Science must be rebuilt on the foundation of openness rather than closure, and engagement rather than detachment, to regain the sense of astonishment. Knowing must be reconnected with being; epistemology, with ontology; and thought, with life (Ingold, 2011).

The Dongaria’s way of worlding, as viewed from a decolonial framework, involves an interwoven existence wherein ties with more than human define existence and “where each connected term in a human-non-human web/network and the way it is connected with others define its identity” (Stengers,2018, 24). Thus, Adivasi thinking is ‘political thinking’, as it offers a contrasting view of governing the collective self and surrounding natural world (Dastidar, 2020, p. 51). The Dongaria’s way of worlding might be characterized as what Guattari calls the “ecosophical perspective” (Guattari, 2000, p. 65) that is applied at once, theoretical, ethicopolitical, and aesthetic. The dominant capitalist subjectivity, which is already eroding social relations and destroying the natural environment, can be countered through an ecosophical problem that aims to reinvent human existence and subjectivity in a new historical context (Guattari, 2000).

Adelman, S. (2015). Epistemologies of mastery. In A. Gear & J. K. Louis (Eds.), Research handbook on human rights and environment (pp. 9–27). Edward Elgar.

Bandyopadhyay, J., & Shiva, V. (1988). Political economy of ecology movements. Economic and Political Weekly, 23 (24), 1223–1232. https://www.jstor.org/stable/4378609

Banerjee, P. (2006). Culture/politics: The irresoluble double blind of the Indian Adivasis. The Indian Historical Review, 33 (1), 99–126. https://doi.org/10.1177/037698360603300106

Barik, S. (2023, October 13). Fight against bauxite mining in Odisha: The view from the hill. The Hindu. https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/fight-against-bauxite-mining-in-odisha-the-view-from-the-hill/article67413877.ece

Bennett, J. (2001). The enchantment of modernity: Attachments, crossings and ethics. Princeton University Press.

Bhabha, H. (1997). Minority maneuvers and unsettled negotiation. Critical Inquiry,23 (3), 431–459. University of Chicago Press. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1344029

Blaser, M. (2009). Political ontology: Cultural studies without ‘cultures’? Cultural Studies, 23 (5-6), 873–896. https://doi.org/10.1080/09502380903208023

Blaser, M. (2010). Storytelling globalization from the Chaco and beyond. Duke University Press.

Blaser, M. (2012). Ontology and indigeneity: On the political ontology of heterogeneous assemblages. Cultural Geographies, 21 (1), 49–58.

Blaser, M. (2013). Ontological conflicts and stories of people in spite of Europe: Towards a conversation on political ontology. Current Anthropology, 54 (5), 547–568.

Borde, R. (2017). Differential subalterns in the Niyamgiri movement in India. Interventions, 19 (4), 566–582. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369801X.2017.1293553

Borde, R., & Bluemling, B. (2021). Representing indigenous sacred land: The case of the Niyamgiri movement in India. Capitalism Nature Socialism, 32 (1), 68–87. https://doi.org/10.1080/10455752.2020.173041

Cameron, A., & Palan, R. (2004). The imagined economies of globalization. Sage.

Coole, D. (2013). Agentic capacities and capacious historical materialism: Thinking with new materialism in political sciences. Millennium: Journal of International Studies, 41 (3), 451–469. https://doi.org/10.1177/0305829813481006

Coole, D., & Frost, S. (Eds.). (2010). New materialism: Ontology, agency and politics. Duke University Press.

Corbin, H. (1972). Mundus imaginalis, or the imaginary and the imagined. Spring Press.

Dastidar, M. (2016). Marginalized as minority: Tribal citizens and border thinking in India. Economic and Political Weekly, 51(25),48–54.

Dastidar, M. (2020). Practices as political: Tribal citizen and indigenous knowledge practices in the East Himalayas. Economic and Political Weekly, 55 (46), 49–55.

De la Cadena, M. (2010). Indigenous cosmopolitics in the Andes: Conceptual reflections beyond “politics.” Cultural Anthropology, 25 (2), 334–370.

De la Cadena, M., & Blaser, M. (2018). A world of many worlds. Duke University Press.

DeLanda, M. (2006). A new philosophy of society. Continuum.

Deleuze, G., & Guattari, F. (1984).Anti-Oedipus: Capitalism and schizophrenia. Athlone.

De Sousa Santos, B. (2014). Epistemologies of South: Justice against epistemicide. Paradigm Publisher.

Escobar, A. (2007a). The ‘Ontological turn’ in Social Theory: A Commentary on ‘Human Geography without Scale’, by Marston, S. Jones II, J.P., and Woodward, K., Transaction of the institute of British Geographers, vol. 32, no. 1, pp. 106-111.

Escobar, A. (2007b). Worlds and knowledges otherwise: The Latin American modernity/coloniality research program. Cultural Studies, 21 (2), 179–210.

Escobar, A. (2016). Thinking-feeling with the Earth: Territorial Struggles and the ontological dimension of the epistemologies of the South. Antropólogos Iberoamericanos en Red, 11 (1), 11–32.

Fox, N. J., & Alldred, P. (2015). New materialist social enquiry: Design, methods and the research-assemblage. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 18 (4), 399–414. https://doi.org/10.1080/13645579.2014.921458

Gadgil, M., & Guha, R. (1993). The fissured land: An ecological history of India. Oxford University Press.

Guha, R. (2007). Adivasi, Naxalites and Indian democracy. Economic and Political Weekly, 42 (32), 3305–3312.

Guattari, F. (2000). The three ecologies. The Athlone Press.

Hardenberg, R. (2016). Beyond economy and religion, resources and socio-cosmic fields in Odisha, India. Religion and Society,7 (1), 83–96. https://doi.org/10.3167/arrs.2016.070106

Ingold, T. (2011). Being alive: Essay on movement, knowledge and description. Routledge.

Jena, M. (2013). Voices from Niyamgiri. Economic and Political Weekly, 48 (36), 14–16.

Jena, M. K., Pathi, P., Dash, J.,Patnaik, K.K., & Seeland, K.T. (2002). Forest tribes of Orissa (Vol. 1). D.K. Printworld.

Kapoor, D. (2011). Subaltern social movement post-mortems of development in India: Locating transnationalism and radicalism in India. Journal of Asian and African Studies, 46 (2), 130–148. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021909610395889

Kapoor, I. (2004). Hyper-self-reflexive development? Spivak on representing the Third World ‘other’. Third World Quarterly, 25 (4), 627–647.

Kovach, M. (2010). Conversational method in indigenous research. First Peoples Child & Family Review, 5 (1), 40–48. https://fpcfr.com/index.php/FPCFR/article/view/172

Kraemer, R., Whiteman, G., & Banerjee, B. (2013). Conflict and astroturfing in Niyamgiri: The importance of national advocacy networks in anti-corporate social movements. Organization Studies, 34 (5–6), 823–852. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840613479240

Krishnan, R., & Naga, R. (2017). ‘Ecological warriors’ versus ‘indigenous performers’: Understanding state responses to resistance movements in Jagatsinghpur and Niyamgiri in Odisha. South Asia: Journal of South Asian Studies, 40 (4), 878–894. https://doi.org/10.1080/00856401. 2017.1375730

Kumar, K. (2013). The sacred mountain: Confronting global capital at Niyamgiri. Geoforum, 54 (3), 389–402. https://doi.org/10.1086/368120

Lahiri-Dutt, K. (2016). Introduction to coal in India: Energising the nation. In K. Lahiri-Dutt (Ed.), The coal nation: Histories, ecologies and politics of coal in India (pp. 1–35). Ashgate Publishing.

Latour, B. (1993) We have never been modern. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Martin, K., & Mirraboopa, B. (2003). Ways of knowing, being and doing: A theoretical framework and methods for indigenous research. Journal of Australian Studies, 27 (76), 203–214. https://doi.org/10.1080/144443050309387838

Mignolo, W. D. (2007). Delinking: The rhetoric of modernity, logic of coloniality and grammar of decoloniality. Cultural Studies, 21 (2–3), 449–514. https://doi.org/10.1080/09502380601162647

Mignolo, W. D. (2011). Geopolitics of and sensing and knowing: On (de)coloniality, border thinking and epistemic disobedience. Postcolonial Studies, 14 (3), 273–283. https://doi.org/10.1080/13688790.2011.613105

Nandy, A. (1994). Development and violence. Culture of peace program. UNESCO. available at https://www.uni-trier.de/fileadmin/forschung/ZES/Schriftenreihe/019.pdf.

Nielson, K. B., & Oskarsson, P.(2017). Industrialising rural India. In Osakarsson, P. and Nielson, K.B. (eds) Industrialising Rural India: Land Policy and Resistance. Routledge.

Oskarsson, P. (2017). Diverging discourses on bauxite mining in Eastern India: Life-supporting hills for Adivasis or national treasure chests on barren lands? Society & Natural Resources, 30 (8), 994–1008. https://doi.org/10.1080/08941920.2017.129549

Pandelton-Julian, A., & Brown, J.S. (2023). In search of ontologies of entanglement. Daedalus, 152 (1), 265–271. https://doi.org/10.1162/daed_a_01987

Ramesh, P. (2017). Rural industry, the Forest Right Act and the performance(s) of proof. In K. B. Nielson & P. Oskarsson (Eds.), Industrializing rural India: Land policy and resistance (pp. 161–178). Routledge.

Restrepo, E. (1996). Los tuqueros negros del Pacífico sur colombiano In E. Restrepo and J. I. del Valle, eds. Renacientes del Guandal, (pp. 243-350). Bogotá: Universidad Nacional/Biopacífico.

Roycraft, D. J., & Dasgupta, S. (2011). Indigenous pasts and the politics of belonging. In S. Dasgupta and D. J. Roycroft (eds), The politics of belonging in India. Routledge.

Saxena, N.C., Parasuraman, S. Kant, P., & Baviskar, A. (2010). Report of the four member committee for investigation into the proposal submitted by the Orissa Mining for bauxite mining in Niyamgiri. Ministry of Environment and Forests, Government of India. https://cdn.cseindia.org/userfiles/Report_Vedanta.pdf

Shah, A. (2007). The dark side of indigeneity? Indigenous people, rights and development in India. History Compass, 5, 1806–1832. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1478-0542.2007.00471.x

Smith, L. T. (1999). Decolonizing methodologies: Research and indigenous peoples. Zed Books.

Stengers, I. (2018). The challenge of ontological politics. In M. de la Cadena and M. Blaser (Eds.), A world of many worlds. Duke University Press.

Sultana, F. (2022). The unbearable heaviness of climate coloniality. Political Geography, 99, Article 102638. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2022.102638

Tatpati, M., Kothari, A, & Mishra, R. (2018). The Niyamgiri story: Challenging the idea of growth without limits? In N. Singh, S. Kulkarni, & N. Pathak Broome (Eds.) Ecologies of hope and transformation, post development alternatives from India. Kalpavriksh and SOPPECOM. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/326972762_The_Niyamgir_Story_Challenging_the_idea_of_Growth_without_Limits

Thompson, A. (2006). Four paradigm transformations in oral history. Oral History Review,341, 49–70. Tripura, B. (2023). Decolonizing ethnography and tribes in India: Toward an alternative methodology. Frontiers in Political Science, 5, Article 1047276. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpos.2023.1047276

[1]Mr. Virendra Kumar is Assistant Professor at the Department of Political Science, Satyawati College, University of Delhi (India). His Ph.D research looks at intersection between Climate justice, climate change and displacement. In addition, his research areas also focus on Eurocentrism, non-western epistemology, subaltern and antiglobalization movements with a special focus on Global South perspectives. Email: virendrakumar@satyawati.du.ac.in

[2] The Kondhs are a larger Adivasi group scattered in three major districts of Odisha: Rayagada, Kalahandi, and Kandhmal. While the Dongaria Kondhs, with an estimated population of 8000 (2001 census), live in the upper reaches of the Niyamgiri hills, the Kutia Kondh inhabit the foothills. The Dongaria Kondhs derive their name from dongar, or hill. These are scheduled tribes with the Schedule V of the Indian Constitution, which enjoins the government to respect and uphold the land rights of scheduled tribes applying to the entire Niyamgiri hill regions. These tribes are also notified by government as a “primitive tribal group” and “eligible for special protection.”

[3] Saxena et al. (2010) has outlined the broad ecological significance of the Niyamgiri hills. An excerpt from the report is as follows: “Niyamgiri Hills is surrounded by dense forest and is habitat for diverse species of plant and animal life. The Niyamgiri massif is important for its rich biodiversity. In addition, it plays a critical role in the living forests of Kandhamal and the forests of the Rayagada, Kalanahdi, and Koraput districts. These forests also join the Karlapat wildlife sanctuary in the north west and Kotagarh wildlife sanctuary in the northeast. The forested slope of the Niyamgiri hills and many streams that flow through them provide means of living for the Dongaria Kondh and Kutia Kondh. They are scheduled tribes.”

[4] During the in-depth interview cum conversation with Laddo Sikka, an elderly Dongaria Kondh from the village of Lakhpadar, the Dongaria’s everyday life practices came to be known. According to him, Dongaria women go to a weekly market to sell their horticultural produce such as fruits and spices and even wood logs and charcoal (made from wood). These local markets are held at different places in the Munniguda block, Lanjigarh block, and other areas. Local activists also confirmed these practices. Dongaria women carrying wood logs can be seen on any normal day in Munniguda. On return, they buy a few essential items from the market. They also practice slash-and-burn cultivation on limited patches of the vast dense forests of the Niyamgiri range, and these patches regrow in 3 to 4 years.

[5] Various local organizations; concerned activist academicians; Marxist organizations, including Maoist organizations that believed in radical politics; and various national and international non-government organizations joined the movement in due course. Niyamgiri Suraksha Samiti (NSS) was formed in 2006 and emerged as an umbrella organization that believes in constitutional means to put pressure on the government not to allow mining Niyamgiri hills and take pro poor, pro Adivasi policies. Radical Marxist organizations are believed to have been on forefront against mining extraction in the region and suffered state repression in various forms. Maoist organizations reject the bourgeois Indian state and capitalist development. They believe in armed revolution and have waged war against the Indian state. Therefore, they have been banned.

[6] In its judgment (Orrisa Mining corporation vs Ministry of Environment Forests and others, Supreme Court writ [civil]No. 180), the court drew on the Panchayats (extension to scheduled areas) Act of 1996 (PESA), which promised to “safeguard and preserve the traditions and custom of the people, their cultural identity, community resources and customary mode of dispute resolution”. Forest Right Act 2006, which was passed during the congress-led alliance UPA regime (left of center regime) at the center, was also invoked granting forest-dwelling communities the right to habitat if they have been living in the forest for three generations and more. The court stated that the duties of the local community in the “scheduled” Niyamgiri include the preservation of habitat from any form of destructive practices that affect their cultural and natural heritages. Scholars such as Prakurti Ramesh critically examined the FRA’s right to habitat, which requires Adivasi/forest dwellers to produce proof of their association with nature and that they are conservationists even as they access and use forest products for centuries.

[7] Most Dongaria Kondhs are critical of the Dongaria Kondh Development Agency’s (DKDA) role. In most villages, the schemes carried out by the DKDA are not done in consultation with the village. There is no follow-up regarding the distribution of items such as solar lamps and seedlings for horticulture. Likewise, local nongovernmental organizations are critical of commission and corruptions involved in the program implementation by officials of the Odisha Particular Vulnerable Tribal Group Empowerment and Livelihood Program(OPELIP), a dedicated department for the development of scheduled castes and tribes of the Odisha government.

9 / December / 2025

By: Gina D'Alesandro

8 / November / 2025

By: Mariana Calcagni G

19 / September / 2025

By: Taylor Steelman

19 / September / 2025

By: Eva Navarro

14 / June / 2025

By: Sarah Steinegger, Nora Katharina Faltmann