December / 9 / 2025

By: Gina D'Alesandro

This article draws upon multispecies ethnographic fieldwork with the Maya Ixil in Iximulew (Guatemala) to identify a model of biodiversity conservation that decolonizes food systems in situ through biocultural practices of care work with more-than-human others. Built in reciprocity, beyond the species model, the Milpa Maya Ixil engineers a multispecies food system, rematriates an Indigenous People to their ancestral territory, and contributes to a global social justice movement. More-than-human caretakers of the milpa and Ixil food and seed sovereignty initiatives generate a local living economy. Ixil biocultural protocols and local notions of development (tiichajil) valorize ancestral knowledge systems and biocultural practices of reciprocity. A decolonized model of biocultural and biodiversity conservation, cycles seeds and abundance from an economy of the soil. The article advocates for recognition, support, and compensation for this critically important care work that the Ixil perform to steward biodiversity in situ.

Maya Ixil, milpa, rematriation, biodiversity conservation, food sovereignty, campesinx, carework

The Nebaj Mercado Campesino—thefirst and largest of several ‘peasant markets’ in the Ixil territory—is located just off Nebaj municipality’s central plaza in the Quiché department of Iximulew, or Guatemala, a predominantly Indigenous Maya region rich in biocultural diversity (Myers et al., 2000). In an otherwise verdant landscape of green on green, each market erupts in a flurry of bright colors. The bright red of the Maya Ixil women’s long traditional skirts and the vibrant colors of their traditional woven huipil blouses seem to allude to the diversity of color from the foods harvested from the land. Here, campesinxs offer raw fruits, vegetables, tubers, flowers, chickens, and seeds, while the smells of prepared and ready-to-eat foods, such as cooked malanga, boxbol[1], and various prepared maize bites, lure in hungry passersby (Figure 1). Ixil artisans offer woven clothing, baskets, pottery, soaps, and body care products—embodying knowledge, time, and workmanship. As biocultural hubs of the highland Mesoamerican food systems, referred to as ‘milpa‘, these markets are vital more-than-human gathering points in landscapes long stewarded by Maya peoples.

Hundreds of Ixil, predominantly women, interlink their enterprises within living economies rooted in the milpa‘s abundance, re/learning land-based practices essential for more-than-human survival. Through these markets, one can observe grounded mechanisms of biocultural diversity conservation in action. The Maya Ixil Mercado Campesino, the earlier Concurso Campesino (peasant competition), the Feria Campesina (award ceremony), and the Escuela Campesina (village-based classes)together form a year-round network of land caretakers fostering multispecies collaboration in situ. These intertwined initiatives sustain a living exchange of Ixil cultural resources, investing daily in biodiversity by supporting the human stewards who cultivate food and seed sovereignty.

Recognizing a new generation of entrepreneurs revitalizing Ixil communal and cultural space, these initiatives draw from the shared material landscape of the milpa to popularize and decolonize Ixil land-based culture and rematriate its actors in more-than-human collaboration. Gaining legal and formal recognition from the Nebaj municipality in 2019, the Mercado[2]–associated initiatives have created spaces for Ixil and Iximulewan peoples to reinvest in their biocultural identity and renew reciprocal relationships with the Earth—acts of rematriation.[3] Restoring Ixil landscapes through the milpa regenerates and restores more-than-human abundance according to Indigenous notions of place[4] (Watts, 2013). For the Ixil, buen vivir—living well (Gudynas, 2011) in and with the milpa—is inseparable from tiichajil[5], the Ixil lifeway (see also Banach & Brito Herrera, 2021). As “using is still the best antidote against losing” (Nazarea, 2006, p.16), caretaking is a structural principle of the Milpa Maya Ixil, embodying multi- and interspecies reciprocities within the food system. By materializing equality, abundance, and justice, the milpa, in the Ixil Region, becomes food and seed sovereignty for a future beyond the human.

Referred to by the Ixil as the revitalization of the decolonial tiichajil lifeway, these living systems of knowledge[6] also serve as effective protection against biodiversity loss. Originating around 2013 with local NGOs focused on biodiversity conservation and cultural revitalization, the initiatives have become central to the substantiation of tiichajil. Emerging from the same soil as the Universidad Ixil[7], they are grounded in Ixil ways of thinking, knowing, doing, and being. Designed to complement and expand material space for Ixil methodologies, ancestral knowledge systems, and Maya spiritual beliefs, they have re-centered multispecies collaborations through the milpa, linking tiichajil theory to the praxis of Ixil food and seed sovereignty.

Rooted in the soil, Ixil rematriation to ‘Mother Earth’ after the immense trauma of state-perpetrated genocide (Sanford, 2003; Grandin, 2004), decolonizes beyond metaphors (Tuck & Yang, 2012) to form a politics of regrowth that restores material connection to land. Shared ancestral traditions of the milpa ground Ixil knowledge systems, and centuries of stewardship in situ sustain a fertile ground for more-than-human restoration as justice and Indigenous transformation (Bagga-Gupta, 2023). For the Ixil, the milpa materializes Maya notions of communitarian feminism (feminismo comunitario) (Cabnal, 2010), or Community Territorial Feminism[8], and the ‘territorio cuerpo-tierra‘[9] (Cabnal, 2010, 2017, 2019; Ulloa, 2016; Sweet & Ortiz Escalante, 2017; Halvorsen & Zaragocín, 2021; Zaragocín & Caretta, 2021), redressing colonial Cartesian separations through land-based, multispecies, and indigenous forms of organization, from the ground up.

While scholars from both Indigenous and Western knowledge traditions have long supported grassroots models of biodiversity conservation (Strandby Andersen et al., 2008; Figueroa-Helland, Thomas, & Aguilera, 2018; Calderón et al., 2018; Prado-Córdova, 2021; Praun et al., 2017), few studies center “biodiversity productive systems with sovereignty and food security or local food systems concepts (<10% of studies analyzed)” (Moreno-Calles et al., 2016, p.9). This article addresses that gap by advocating for recognition, support, and compensation for more-than-human land caretakers who steward landscape-scale biocultural diversity in their ancestral territories. Ixil land-based, more-than-human knowledge systems structure biocultural protocols[10] (Bavikatte & Jonas, 2009; Bridgewater & Rotherham, 2019) that position the human as one among many, bound by a responsibility to care for multispecies communities. Through the Milpa Maya Ixil, the article responds to the questions: How do Ixil initiatives rooted in the milpa serve as a model of biocultural diversity conservation, in situ? How do these practices embody a decolonized cultural notion of sustainability grounded in Maya Ixil cosmologies and worldviews?

The following sections relate the milpa‘s multispecies biocultural conservation model to its historical Maya precedents and examine how the contemporary Mercado, Concurso, Feria, and Escuela Campesinx initiatives enact this model today. Using multispecies ethnographic methods, I document processes like native seed diversification and exchange, the re-creation of landscapes through between more-than-human kinship, the assembly of new kin networks as species are introduced into the milpa; and the revitalization and re-valuation of the wisdom of elders and traditional governance systems that weave humans into the milpa. At its core, the more-than-human duty to care for the Milpa Maya Ixil anchors Ixil ontologies, cultivating reciprocal abundance for all caretakers and sustaining vibrant, land-based economies that decolonize the tiichajil lifeway through ‘rematriation.’

Working from a feminist, beyond-the-human framework for data collection and analysis (Haraway, 2016), this multispecies ethnographic research[11] formed part of my doctoral work with the Maya Ixil Indigenous People in the Ixil territory of Iximulew/Guatemala. The research was conducted over 14 months, from October 2018 to March 2020. As an invited researcher, I examined the restorative and regenerative food systems of the Ixil. Contextual documentation of the in situ and lived experiences of violence—arising from top-down global structures of inequality, colonialism, and extractivist development[12]—was included in the data collection to situate these ‘culture’-d ecosystems of life within broader systemic constraints.

The narrative approach, or “multispecies storytelling in the feminist mode” (Haraway, 2013, p.2), drew on empirical data from semi-structured interviews, milpa (field) and market visits, forest walks with campesinx land caretakers, which began with 6 months of volunteering[13]. These were complemented by participant-observation in both informal and formal settings, including homestays, classes at the Universidad Ixil, and collaborative work in family food systems. As a guest in the Ixil territory, my ‘multispecies’ engagements were conducted exclusively with Maya Ixil human caretakers.

Data analysis involved transcribing field notes and interview materials, which I coded thematically. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, emergent themes and specific variables were identified outside of the Ixil Territory. This perspective reflects a situated but globally reflective analysis that informed the study’s conclusions and framed its presentation in dialogue with relevant literature. In that, the research evolved as intersectional and anti-colonial work by following an ethic of invitation—going and documenting only where I was asked or welcomed. In this sense, the feminist method was enacted as a practice of expanding spaces of equality.

By reporting on the top-down structures and their effects ‘from below’, through lived observations of the anthropocentric harms driving social inequality, ecological collapse, and the taking/loss of lifeforms, these methods also confront the systems and social structures that undermine the work of those who care for the Earth. Such praxis aligns with community-based or communal work[14] (Tzul Tzul, 2018) and stands in solidarity with pluriversal perspectives of Indigenous thought (Blaser & de la Cadena, 2018; de la Cadena and Blaser, 2018). Through this work, we enact political and biosocial change—’rematriating’—as ‘multispecies’, a more-than-human collective.

My use of these terms is deliberate: I acknowledge “Madre Tierra”[15] as a multispecies mother we all share, the soil as her body, and the basis for the life and food of a “complex we[16]“. Multiple and diverse agencies are embedded in the exchange of energy produced through labors of, to, and for Her (Cabnal, 2010; Ulloa, 2016; Sweet & Ortiz Escalante, 2017; Halvorsen & Zaragocín, 2021; Zaragocín & Caretta, 2021). My positionality within this work, thus, is as a ‘kin-making guman’, “that worker of and in the soil” (Haraway, 2013, p. 8).

A study from Guatemala’s Petén department highlights a critical difference between Indigenous Maya and ladinx-Indigenous mixed or immigrant indigenous groups: the Maya cultivate a greater diversity of crops (Atran et al., 1999). The Guatemalan conservation agency, the Consejo Nacional de Areas Protegidas (CONAP), confirms that traditional agroecological systems sustain higher biodiversity (CONAP, 2008). The milpa food system of Iximulew, home to some 24,000 indigenous plants (Ford, Turner, & Mai, 2023, p.12), is one such system shared across Guatemala and Mexico. Composed of crops endemic to the region, the milpa often contains the highest biodiversity in the landscape (Heindorf et al., 2021). Within it, plants occupy different ecological niches, forming synergies, complementing functions, and modifying the microclimate to enhance productivity (Fonteyne et al., 2023, p. 2).

Plant remains recovered from ancient Mayan sites show that milpa biodiversityextends to the Mayan civilization (Atran et al., 1993, p. 676; Islebe et al., 2022). While maize, beans, and squash formed dietary staples, the Maya also cultivated numerous other crops domesticated locally but of global significance today (Islebe et al., 2022). These pre-Columbian foodscapes, which “underwrote the development of the Maya civilization”, were designed and sustained by a growing human population through diverse and intensively managed plots (Ford & Nigh, 2009, p.214).

Often called “Maya Forest Gardens”[17] (Ford & Nigh, 2009, p.223; Ford & Nigh, 2015), this ancient resource management system remains visible today “both in the structure and composition of the Maya Forest and in the current resource management practices of the Maya [Peoples]” (Ford and Nigh 2009, p.215). The milpa continues to prove climate-resilient, providing diverse, nutritious food throughout the year, and generating income from surpluses (Fonteyne et al., 2023; Falkowski et al., 2019). It also endures drought[18] (Islebe et al., 2022), and when intercropped with trees, produces higher maize yields due to improved microclimates (Molina-Anzures et al., 2016, cited in Fonteyne et al., 2023, p. 9). An example of ethnoagroforestry (Moreno-Calles et al., 2016), milpa systems are “more productive” than monoculture (Lopez-Ridaura et al., 2021; Fonteyne et al., 2023, p. 10[19]).

For many Maya, saving seed on-farm is synonymous with “being a good farmer” (Badstue et al., 2007, p.1584; Almekinders, Louwaars, & De Bruijn, 1994), and is a central driver of biodiversification (Fonteyne et al., 2023). “Each farmer maintains and reproduces one or more landraces and only infrequently engages in a seed exchange” (Badstue et al., 2006, p.267), often as a strategy to replace lost seed.[20]

The farm of Concurso Campesino-certified™ Ixil farmer, Christopher, biodiversity caretaker and assessor for the Mercado Campesinos, exemplifies this in situ diversity (Figure 2). When he guided me through his 5 cuerda[21] parcela in July 2019, he described the region’s varied growing conditions and pointed out the wide array of fruits, vegetables, trees, and flowers in his milpa. Each patch of soil was prepared meticulously[22] so that plants might accept the space and thrive together[23]. During a gathering of Ixil campesinxs in Xemamatze village with Mam campesinxs from Huehuetenango (part of the Escuela, described in subsequent sections), Christopher reflected on the role of native seeds as the foundation of all biodiversification in the territory:

…there are many semillas nativas [such as] haba, güisquil, maize, [etc. in our programs]. The idea is to have exchange between the group members. … the idea is to valorize the cultivars and campesinxs… Those with the highest quantity of cultivars, these are the ones that compete separately in the Concurso. The objective of doing the Concurso is the valuation [and valorization] of native crops, [to] value our native seeds. To value [this], that is the fundamental objective. And the other thing is to make food for the family, […] People realized that now we have some food to eat, some plants to eat, but still, we are poor, so what do we do? From there, they themselves […] organized the Mercados and it was in this way they began. But the fight continues, the motivation of the farmers is that there is biodiversity. […] the importance of biodiversity, that’s where we are at.

Christopher described the evolution of his milpa as an ongoing process of reproducing biodiversity through ancestral knowledges and seed experimentation. Each plant carried its own story of arrival. Gesturing to a lower slope, he drew my attention to a patch of several different passionfruit plants, all adapted to his milpa‘s tierra templada conditions. One, bearing a single small yellow fruit, had been grown from a seed he bought for 35 Quetzales (US$4.5) in the nearby Indigenous capital Xela (Quetzaltenango).

Supporting and adding value to farmer experimentation, Ixil-led community initiatives have encouraged Christopher to record the germination of new plants. Juan, a fieldworker with FUNDAMAYA—the Universidad Ixil–affiliated NGO that coordinates funding for Campesino programs—explained the close links among the Mercados, the Concurso Campesinos that evaluate biodiversity, and the final certification and award event held at harvest time, the Feria Campesina.[24] He explained that the Concurso begins each September, when fieldworkers are dispatched weekly to the four Mercado sites. They track campesinx attendance and document crop diversity until December, when results from all markets are compiled (Figure 3). The season culminated in the Feria Campesina, a celebration of the milpa‘s abundance (Figure 4).

During the Feria, prizes recognize farmers who participate most frequently in the Mercados, bring the greatest diversity of crops, or cultivate the best quality varieties—evaluated for both gastronomic and morphological excellence. In this way, campesinxs receive tangible appreciation for their carework in sustaining biodiversity and the tiichajil living economy.

As of 2022, the Concurso network included roughly 300 families across 25 Ixil communities. According to FUNDAMAYA, more than 7,000 cuerdas of registered milpas collectively host over 80 different cultivars, based on records from the most recent Concurso (Universidad Ixil, 2021).

Incentivizing others across the Ixil Region through observation and word-of-mouth, winning campesinxs and the emergence of Concurso Campesino-‘certified’ farmers have generated new momentum to value communal work in the milpa (Tzul Tzul, 2018; McCarthy et al., 2018). From his own certification process, Christopher explained that entering the competition pushed him to begin documenting his milpa experiments two years earlier, creating a list of his plants and updating it regularly. His certification, he said, is not only agricultural but political—a performance of Ixil identity that reclaims body-territory (Cabnal, 2010, 2017, 2019) by deepening reciprocities with the land. Framed within ancestral Maya knowledge systems, this work has strengthened his resolve to pursue food and seed sovereignty. Christopher views this initiative as a source of empowerment to enrich and experiment with biodiversity in both his milpa and diet. Recognized by his community as an expert, his certification also identifies him as a reservoir of knowledge within a network of farmers revitalizing tiichajil in their territory.

Experimenting with seeds and evolving tastes, global processes also shape life within the Ixil milpa. Mobility and migration—driven by persistent inequality that forces Guatemalans (U.S. Customs and Border Protection [2024]) and Maya Ixil to the Global North (Heidbrink, Batz, & Sánchez, 2021)—carries seeds across lands, inspiring new assemblages through this assisted exchange. At the Tzalval Mercado on November 6, 2019, I noticed an unusual fruit in a basket of native güisquil vegetables (Figure 5). Pale green but distinct in shape and texture, it was identified by a young woman with a baby on her hip as a guava variety originating in the US. Her father had collected and mailed the seed from there, and it now grew in Nebaj’s Xemamatze village. Initially unfamiliar, she described its taste as pleasantly sweet, adding that the plant had adapted well to the Ixil region’s tierra templada climate. Through such experimentation, Ixil families expand biodiversity and strengthen food and seed sovereignty. Mediated by the evolving tastes of those who cultivate and exchange new varieties, Ixil initiatives like the Mercado continue to evolve, materializing new biodiversity combinations along the tiichajil pathway.

The expansion of the Mercado initiative to multiple sites across the Ixil Territory has deepened biocultural diversity across its many microclimates. Although the region is commonly described as having three climate zones—’tierra caliente‘ (hot), ‘tierra fría‘ (cold), or ‘tierra templada‘ (warm and wet)[25]—Ixil campesinxs like Christopher identify six to ten distinct microclimates. Exceptionally diverse for Central America and one of the region’s two areas with a history of late Pleistocene glaciation (Lachniet, 2004; Steinberg & Taylor, 2008), the western highlands of Iximulew amplify these exchanges of biocultural diversity. Nebaj, the territory’s most populous municipality, consistently contributes the largest and most varied milpa offerings to its market. As Christopher puts it, it is “a good place for campesinxs to sell”. Describing the Sumalito Mercado, he explained how local climates and crops influence demand across markets:

[In] Sumalito, the climate is temperate, between [tierra] caliente and [tierra] templada. […] [W]hat happens is that there is not much exchange [amongst themselves], but this is because they [already] have [what is being offered]. For example, let’s say we are talking about bananas, pacaya [Chamaedorea tepejilote; Arecaceae], oranges, lemons, [etc.]. Almost everyone [there] has them, right? So, if someone brings bananas and enters the market, they almost won’t sell [anything] because everyone [already] has [bananas]. Now, what they do [instead] is that they bring them from there—that is, they bring them from Sumalito and sell them here in the Nebaj market. They sell them here because here in Nebaj there are no bananas, so, here, they have an advantage.

Ixil farmers recognize that climatic and landscape variations produce distinct traits in the same cultivars which circulate through Mercado networks. Christopher explained this difference between the root vegetable malanga and maize.

For example, if there is some land and it is one’s vocation, let’s say, [to grow] malanga, it is advisable to plant it on land that is tierra templada. Because if it is planted on tierra fría then yes, it is going to grow, the malanga will come out, but it will be there for a year or 2 years as the malanga becomes [ready]. […] In the tierra templada or in tierra caliente, [it is ready in] almost in 3 months or 6 months. In other words, malanga in temperate climates grows faster. The advantage of tierra caliente is [that it grows fast].

If we sow it in tierra fría and the malanga comes out, it’s [also] that the time to eat it is something a bit tricky. It will not give the same flavor as in tierra caliente. [Also,] in tierra caliente the malanga arrives to this size [gestures a width of about half of a meter]. There, the malanga is of 5, 8, or 10 pounds. It changes in tierra fría– you will see the malangita[26], but it will be of 2 pounds or 1 pound [only]. […]

[T]he other advantage that the [milpas] have in tierra caliente is that there they harvest twice. They grow maize twice. That’s a big advantage that they have. In comparison, in tierra fría they grow maize only once.[27]

As the Ixil eat and use many parts of the same plant, every type of milpa has its strengths. Farmers cross-pollinate across microclimates through the Mercados, where they exchange cultivars and knowledge. Beyond maize, beans, and squash, the leaves of these milpa staples are key ingredients in Ixil diet—used to wrap food, adding nutrition and flavor. Differences in cultivar and plant-part productivity between regions create further opportunities for biodiversification. Farmers specialize in different markets based on demand (Guzzon et al., 2021, p.8), selecting distinct plant parts or seeds to enhance specific plant traits. Highlighting how each milpa excels in certain plant parts, Christopher remarked:

The ayote[28] in tierra fría provides a harvest, but only in herbs—only one [edible] flower and the leaves. With tierra fría, there you are going to have [a lot of] herbs, let’s say. The advantage of the tierra fría is that, for example, any kind of herbs [grow] in tierra fría. Already in tierra templada, herbs [are] difficult […] [to grow] because there [is meant for] another crop.

In tierra templada, there it doesn’t give much in herbs. What it gives [there] is fruit. And, as the people say, it is fruit [that is most desirable]. Let’s say there is ayote [and another of another kind of squash, chilacayote (Cucurbita ficifolia)]— so there are variants. In the case of tierra caliente, for example, if you want your chilacayote, you won’t get [it]. Chilacayote will only give a good fruit in tierra fría. [This is why markets like] Nebaj and Salquil have chilacayote fruit.

Learning the strengths of one’s milpa brings tangible benefits for food and seed sovereignty. Awareness of regional biodiversity enables farmers to leverage the Mercados’ seed networks to build abundance through stable exchange. The consistent demand at the Mercados also allows many campesinxs to reinvest in the tiichajil living economy through steady weekly income.

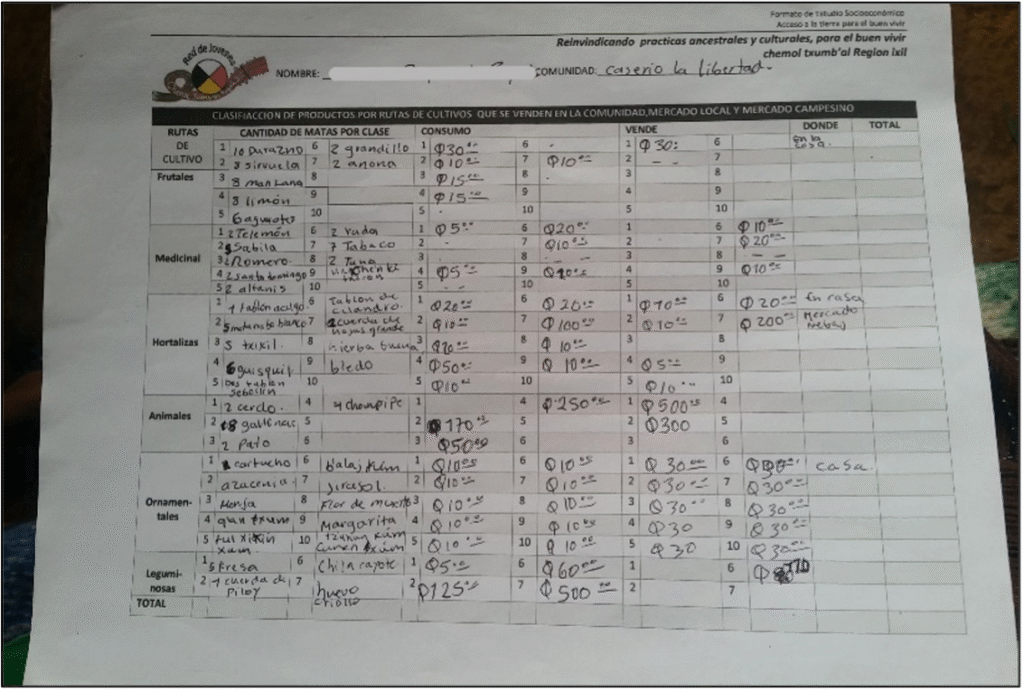

Doña Reza, a regular market participant for four years, focuses her efforts on a single site where she sells traditional staples like ayote, supplemented with produce specific to her microclimate. Her colleague, Doña Caban, attends at least one Mercado weekly, earning a modest income from her diverse offerings. At each market, she says she regularly brings “medicinal plants, leaves for tamales, sometimes cilantro, turnip, herbs, aloe vera plant, chile Chamborone, cepaiche [tomate de palo] […] I try to carry a little bit of an assortment.… always my sales bring 100, 150, or 200 Quetzales per market visit.” (US$13-26). Most of her income goes toward family essentials like sugar and her husband’s medication. Surveys from the youth group Red de Jovenes confirm similar earnings among participating campesinxs across the region (Figure 6).

Settled in the warmer tierra caliente village of Sumalito in the Chajul municipality, campesinxs like Doña Melen and Doña Vujux profit in the Mercados through strategies that sell collected, non-domesticated milpa plants like zacate[29] and bledo.[30] Harvesting plants that the milpa “plants itself”[31], the Mercados reinvest in these management forms by compensating campesinxs for their labor within them. This is a specialization that, as Mercado facilitator Xi’ben explains, happens “by area and by demand, because everyone also specializes in what there is.” Building on regional knowledge and diversity, the formal Mercados, as Christopher notes, are “taking advantage of a space that is now strong to share them”.

Through these initiatives, another layer of Ixil society emerges—one that supports and channels further investment in biodiversity as a land-based biocultural process, fostering more-than-human abundance with and through these feedback mechanisms.

The intensification of biodiversity from a shared responsibility of all to provide care

Building back biodiversity requires rebuilding its biocultural systems of support. Maya Ixil health specialist Xi’ben explained that caring for the milpa is a cultural obligation—one passed from one Ixil generation to the next:

Here our contribution as an Ixil Region is to explain a little about the relationship we have with nature, the relationship we have with agriculture. Without agriculture, we cannot live. But it is important to deepen the study to understand that we are part of the Maya cosmovision. Why Maya cosmovision? We have to understand that our grandparents were very wise, they were thinking people, people who also took actions with responsibility, and that is what we have continued practicing.

Connected to Maya spirituality, as farmer Pedro Guamche of the Maya Achí territory states, farming the milpa “is so much more [than a food or economic exchange]. It’s spirituality. It’s a vital connection with nature” (Einbinder et al., 2022, p. 991). This reflects the Maya cosmovision, in which all lifeforms in the web of life are equal (Cabnal, 2020, cited in Patiño Niño, 2023). Even Maya living in urban areas continue to “insist on planting corn in their communities to maintain a connection to the rajawal“[32] (Carey, 2009, p. 285). Xi’ben explains that this equality is expressed as maintaining equilibrium, a responsibility of the Maya:

… [I want to] share with you our relationship with the cosmovision and agriculture because we have to understand that agriculture is also cyclical. The cosmovision tells us that we have to have equilibrium. The system of life and whatever system in the universe is in equilibrium. To lose, not care for, destroy any of this equilibrium, this will generate disorder. For this, we have to understand as humans that we are an element in our cosmovision because sometimes we are told that to be human is superior, we are intelligent, we are the owners of everything. That is a lie.

In the milpa, no species holds hierarchical importance or control over another. Literature on food sovereignty, referencing “a re-connection to land-based food and political systems” (Martens et al., 2016, p. 18), highlights practices of mutual benefit among species (Kamal et al., 2015) as part of “sacred responsibilities to nurture relationships with our land, culture, spirituality, and future generations” (Morrison, 2011, p. 111, emphasis mine) and “share[d] reciprocal duties as citizens of shared territories…” (Todd 2016, p.17, emphasis in original). Echoing Nadasdy’s (2003) observation from a Kluane First Nation member “(traditional knowledge) is not really ‘knowledge’ at all, it’s more a way of life.” Beyond food sovereignty or economic gain, for Maya lifeways, the milpa food system continues to serve as a central, beyond-the-human metaphor (Fox Tree, 2010, p. 100).

Within the Ixil concept of tiichajil—an Ixil development pathway and philosophy of reciprocal care—this metaphor gains situated, biocultural significance, articulating biodiversification as an Ixil lifeway. Connecting the milpa‘s biodiversity with decolonial movements, a final initiative, the Escuela Campesina[33], provides a year-round pedagogical complement to the Mercado cycle, helping to connect, assemble, and share resources within the Ixil knowledge system.

A hands-on, community- and family-based campesinx-a-campesinx self-education initiative, the Escuela formally organizes the further proliferation of biodiversity. Restoring and strengthening the ‘tejido social‘[34], the Escuela employs Ixil methodologies and epistemologies to host intensive, village-level workshops on knowledge, materials, and seeds. These workshops enhance milpa biodiversity and bring Ixil campesinxs together in active, year-round engagement and shared learning toward common goals of on-farm diversification.

Juan, a facilitator of Escuela, proudly emphasized that the initiatives behind the Mercados and Concursos had matured into the development of the Escuela. As a ‘school’, itnecessarily draws on Ixil cultural practices and milpa-based as land-based methodology and pedagogy (Pinheiro-Barbosa & Gómez-Sollano, 2014; Simpson 2014; Tuck, McKenzie, & McCoy, 2014; Rosset et al., 2019). It prepares campesinxs for each year’s Concurso by providing a framework for explicit collaboration, seed exchange, and peer learning in situ within their milpas.

In the Escuela, certified farmers from previous Concursos are paired with newer campesinxs in small village groups. These groups visit one another’s milpas, workshop methods, and farming practices, and diversify their plots through micro-scale local seed exchanges emerging from these collaborations. Experienced farmers like Christopher and Don Dominic—who earned certification in earlier Concursos—are recruited as teachers and local nodes of biocultural diversity conservation, sharing expertise and resources among neighbors.

Meeting campesinxs directly at their milpas, the Escuela enables participants like Doña Reza to take part in this”school outside of school” as adult learners from their own villages. They co-create the curriculum based on local needs and discover, among neighbors and fellow campesinxs, what skills and knowledge exist within each learning group that can be mobilized for common benefit. A member of Nebaj Mercado‘s Junta Directiva[35], Doña Reza explained that she learned to create medicinal plant products—now her specialty at the Mercado—through workshops and market-tangential events in her territory. Pointing to bottles of her handmade shampoo (Figure 7), she told me at one Nebaj Mercado how she learned to make these local plant-based products from other women’s workshops in her community.

The network of campesinx-a-campesinx methods developed through the Escuela consolidates and sustains community-based, culturally-Ixil knowledge hubs. It allows Ixil people to connect or re-connect with the philosophy of tiichajil by living it as a decolonial, more-than-human lifeway. Closely tied to both the Concurso and Mercado, the Escuela amplifies each by linking Ixil theory from the students and elders of the Universidad Ixil. Forming a campesinx-a-campesinx (Holt-Giménez, 2006) latticework, the Escuela extends roots into the soil, incorporating more-than-human teachers into an education that nurtures autonomy, dignity, and collective justice as the Ixil pursue food and seed sovereignty from within their own traditions.

At the Universidad Ixil, the Ixil notion of tiichajil is theorized from within academia. The University builds its teaching around these initiatives, incorporating and articulating them as transformative institutions of milpa engagement that perform biocultural practices as forms of more-than-human social justice. Encouraging people of all ages to engage with Ixil methodologies and ontologies through action-based research projects, the University studies these initiatives as performances of decolonization that reclaim maize and the milpa as sacred. Revitalizing frameworks that guide Ixil ways of knowing, being, and doing, these projects help the community grow beyond historical injustice. Through milpa-based practices and performances of tiichajil, Ixil lifeways address entrenched structures of inequality (Wolfe, 2006) and restore Ixil autonomy, enabling life in their territory according to intergenerational and interspecies agreements. Xi’ben, also a Universidad Ixil graduate, elaborates:

Our work is that through our young people we can create some technicians, some professionals that respond to the needs of the communities, of the principals, of our authorities. What we want is to create young people that are functional, not [just] to graduate. Here, what we want is that they learn our communitary norms. They must practice our norms, our ways of being. They must know their history. They must know their territory. In this way, they are going to give value to it, they are going to have the opportunity to think, to analyze, to discuss, and to propose what we need. The idea is to build to heal all the wounds to make everything better. [This is] how to return autonomy to our community.

Protecting biodiversity by maintaining biocultural protocols

Drawing upon Ixil knowledge holders and grounding them in existential and epistemological notions of sustainability (Bagga-Gupta, 2023), the Escuela draws deeply from Ixil knowledge systems that reaffirm the relevance of biocultural and social norms. By allowing Ixil ‘laws’ to evolve through these initiatives, Ixil culture continues to grow in tandem with milpa biodiversification.

During a visit to the Tzalbal Mercado on November 6, 2019, Christopher and I met a woman known across the Ixil municipalities for her ‘caña‘[36] baskets, woven from native grass found high in the Ixil mountains. Because the Mercados prohibit plastic bags, following the lead of Maya neighbors in Sololá who initiated a similar environmental restoration initiative (May, 2021), many families commission her baskets in various sizes for different uses. She explained that she produces many of them during the religious week of Semana Santa in March or April, and receives steady orders through the year through word-of-mouth as the Tzalbal Mercado grows.

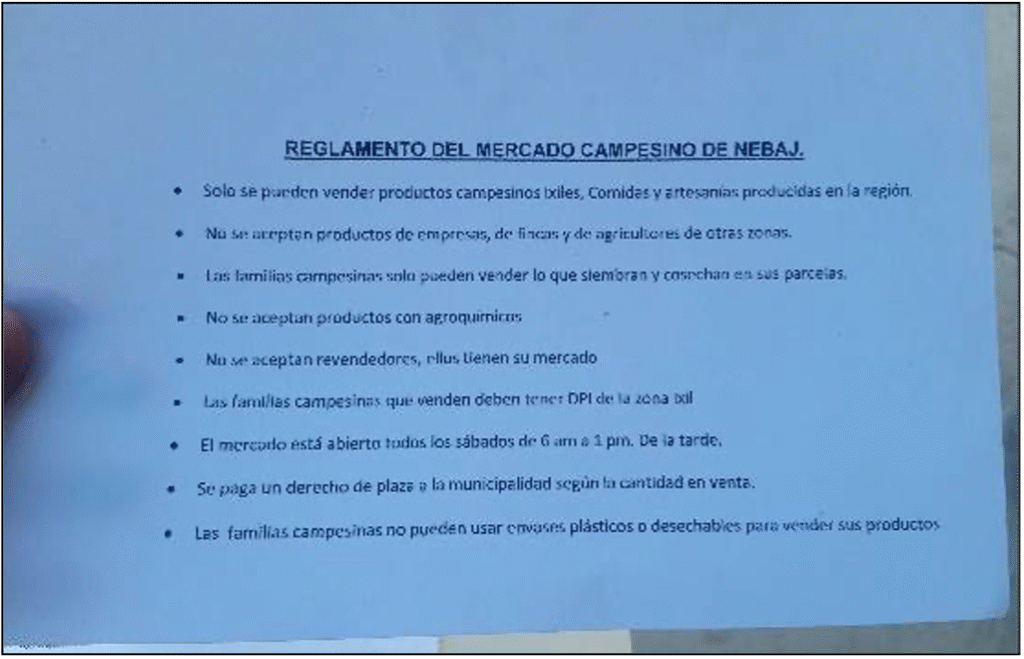

However, her production depends on the plant’s seasonal availability; she must walk several days to harvest it. The grass’ location remains a closely guarded secret to allow its natural regeneration each year. Her practice reflects txaa[37], Ixil cultural regulations rooted in ancestral knowledge and multispecies conservation that extend beyond the milpa. Ixil knowledge systems safeguard biodiversity through these ethical norms or ‘laws’, which govern relationships among humans and other species after centuries of co-evolution. The Ixil initiatives incorporate this framework of ‘laws’ into their design, requiring campesinxs to follow them to participate. Christopher often emphasized a rule established with the Nebaj Mercado: “People have heard that there is a market here [but] there are regulations. They are welcome here, but without chemicals.[38] This is the regulation, otherwise [they cannot sell their goods here].”

Formed through traditional communal decision-making and consensus, such regulations (Figure 9) extend ancestral relations with the more-than-human world into the living definition of sustainability through reciprocity. In achieving food and seed sovereignty, txaa reminds people to take only what is needed and to give back to the soil, plant, and land in return—cycling labor toward shared abundance.

Campesinxs like Christopher speak proudly of their community work, “breaking barriers” of oppression as they use ancestral wealth to conserve biocultural abundance. “MAGA[39] gives food as a gift. So, with the Concurso we don’t depend on gifts, [it is] breaking those barriers.” These barriers, remnants of colonial dependency, are being dismantled through milpa reciprocities decolonized and strengthened by these initiatives. As Christopher reflected, “The idea that we have is not that we are asking for a gift from the government. If you don’t [beg], you [become] activated, look at what we have! This is a bit the idea.”

Using protocols that reinforce biodiversity by Ixil design, campesinxs like Doña Caban ask simply for the sovereignty to continue their stewardship—work they value and enjoy:

The idea is that we get value [from the Mercados] and possibly through you who come to visit us [at them]. It will explain to the people to become conscious that [they have] to give value [to] all of this. Also, that this is work. … not a hobby or [done for] ornamental purposes. Because I also like [this work], and I dedicate myself to it, only.

By paying campesinxs like Doña Caban to “get to know the plants” and cultivate reciprocal care, these milpa-based initiatives foster multispecies abundance and spiritual renewal, rematriating ancestral knowledge systems.

Meq’, a young campesino passionate about ancestral teachings and committed to spreading awareness of these efforts, described this process as “re-campesin-izing”. Inspired by his mentor—an Ixil apiarist who tends his milpa using traditional methods while caring for seven kinds of bees—he represents a new generation of caretakers. Without such successors, the milpa in these forms risk disappearance, with its biodiversity.

Central to the consolidation of these initiatives as in situ institutions of biocultural diversity conservation is the transfer of Ixil culture and knowledge. These exchanges strengthen the tiichajil lifewayby embodying it through practice. At a time when the milpa is endangered, as maize is increasingly grown without its companion crops (Lopez-Ridaura et al., 2019), traditional knowledge systems sustain indigenous relationships of care and stewardship with the more-than-human world, offering biodiverse abundance and decolonized models of ‘good living’ from the pluriverse for all of us to learn from.

The institutions of the Milpa Maya Ixil documented in this article—the Mercado Campesinos, Concurso Campesinos, Feria Campesinas, Escuela Campesina, Universidad Ixil, and numerous other initiatives led by campesinxs across Iximulew (such as Einbinder et al., 2022)—have built a popular movement grounded in Indigenous methodologies and ontologies that sustain traditions of care in the milpa. These traditions rematriate people through a model of biocultural diversity conservation that revitalizes Indigenous knowledge systems and offers a glimpse of what more-than-human abundance and a decolonial economy for a sustainable future can provide.

However, unsupported by nation-states and international policies with legislative power to shape global investment, Indigenous people like the Maya Ixil cannot, and should not, be expected to sustain this work alone. The biocultural wealth the Ixil maintain, following ancestral traditions that channel labor toward the creation of more-than-human abundance, deserves recognition and support. If biodiversity conservation is our goal, we cannot afford not to invest in these initiatives.

The initiatives discussed here demonstrate that the Ixil already possess mechanisms of biodiversity conservation that expand and enact the tiichajil lifeway while reweaving the tejido social after historical trauma and creating opportunities for Ixil economic participation. The Milpa Maya Ixil stands as an in situ, decolonial, and human-rights-based biocultural model of biodiversity conservation that shows how humans can live in equality and reciprocity with the other-than-human. For the Maya Ixil, this model is simultaneously a revitalization of their own knowledge systems.

Biocultural diversity models like this one expand biodiversity by supporting its indigenous caretakers with seeds, resources, encouragement, and reciprocal economic relationships that allow them to continue intergenerational traditions proven resilient over centuries (Islebe et al., 2022). Viewed from this perspective, the milpa (Figure 11) is not only a tool for biodiversity conservation; it also a foundation for food and seed sovereignty. It performs more-than-human justice by actively addressing inequality and helping Indigenous peoples lead the healing of relationships to land and a more-than-human world.

This research was funded in part by the Central European University’s PhD Field and Archival Research and Doctoral Research Support Grants.

Almekinders, C. J., Louwaars, N. P. & De Bruijn, G. H. (1994). Local seed systems and their importance for an improved seed supply in developing countries. Euphytica 78: 207-216. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00027519.

Atran, S., Chase, A. F., Fedick, S. L., Knapp, G., McKillop, H., Marcus, J., Schwartz, N. B. & Webb, M. C. (1993). Itza Maya tropical agro-forestry [and Comments and Replies]. Current Anthropology 34(5): 633-700. https://doi.org/10.1086/204212.

Atran, S., Medin, D., Ross, N., Lynch, E., Coley, J., Ucan Ek’, E. & Vapnarsky, V. 1999. Folkecology and commons management in the Maya Lowlands. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 96: 7598-7603. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.96.13.7598.

Badstue, L. B., Bellon, M. R., Berthaud, J., Juárez, X., Rosas, I. M., Solano, A. M. & Ramírez, A. (2006). Examining the role of collective action in an informal seed system: A case study from the Central Valleys of Oaxaca, Mexico. Human Ecology 34(2): 249-273. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10745-006-9016-2.

Badstue, L. B., Bellon, M. R., Berthaud, J., Ramírez, A., Flores, D. & Juárez, X. (2007). the dynamics of farmers’ maize seed supply practices in the Central Valleys of Oaxaca, Mexico. World Development, 35(9), 1579-1593. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2006.05.023.

Bagga-Gupta, S. (2023). Epistemic and existential, E2-sustainability. On the need to un-learn for re-learning in contemporary spaces. Frontiers in Communication. 8: 1081115. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcomm.2023.1081115.

Banach, M. & Brito Herrera, E. (2021). Buscando eela chil vatz en el tiichajil tenam: El concepto del buen vivir en el pensamiento Maya Ixil. Maya America: Journal of Essays, Commentary, and Analysis 3(3): 49-69. http://DOI.org/10.32727/26.2022.4.

Batz, G. (2021). La Universidad Ixil y la descolonización del conocimiento. Maya America: Journal of Essays, Commentary, and Analysis 3(1): 112-126. http://dx.doi.org/10.32727/26.2021.31.

Bavikatte, K. & Jonas, H. (Eds.). (2009). Bio-cultural community proto‐cols. A community approach to ensuring the integrity of environmental law and policy. United Nations Environment Programme and Natural Justice. https://www.unep.org/resources/report/bio-cultural-community-protocols-community-approach-ensuring-integrity.

Bellon, M., Hodson, D. & Hellin, J. (2011). Assessing the vulnerability of traditional maize seed systems in Mexico to climate change. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 108:13432-13437. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.110337310.

Blaser, M. & de la Cadena, M. (2018). Introduction: Pluriverse proposals for a world of many worlds. In M. de la Cadena & M. Blaser (Eds.). A world of many worlds. (pp. 1-22). Duke University Press. https://doi.org/10.1215/9781478004318-001.

Bridgewater, P. & Rotherham, I. D. (2019). A critical perspective on the concept of biocultural diversity and its emerging role in nature and heritage conservation. People and Nature 1(3): 291-304. https://doi.org/10.1002/pan3.10040.

Cabnal, L. (2010). Feminismos diversos: El feminismo comunitario. ACSUR-Las Segovias, Guatemala.

Cabnal, L. (2017). Tzk’at, Red de sanadoras ancestrales del feminismo comunitario desde Iximulew-Guatemala. Ecología Política 54: 98–102. http://www.jstor.org/stable/44645644.

Cabnal, L. (2019). El relato de las violencias desde mi territorio Cuerpo-Tierra. In X. Leyva & R. Icaza (Eds.). En Tiempos de Muerte: Cuerpos, rebeldías, resistencias, vol. IV. (pp. 113-126). Editorial Retos, CLACSO, Institute of Social Studies, Erasmus University Rotterdam.

Calderón, C., Gerónimo, C., Praun, A., Reyna, J., Santos-Castillo, I. D., León. R, Hogan, R. & Prado- Córdova, J. P. (2018). Agroecology-based farming provides grounds for more resilient livelihoods among smallholders in Western Guatemala. Agroecology and Sustainable Food Systems 42(10): 1128–1169. https://doi.org/10.1080/21683565.2018.1489933.

CONAP (Consejo Nacional de Áreas Protegidas, GT). (2008). Guatemala y su biodiversidad: un enfoque histórico, cultural, biológico y económico. Guatemala. Accessed 4 Nov 2022. Available at: https://sip.conap.gob.gt/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/Libro-Guatemala-y-su-Biodiversidad_2008.pdf.

D’Alesandro, G. (2024). More-than-human conservation, models from the pluriverse: the example of biocultural diversity conservation from knowledge systems of the Maya Ixil in the Maya Ixil Territory. Global Social Challenges Journal 3(2): 198-239.

https://doi.org/10.1332/27523349Y2024D000000028.

de la Cadena, M. & Blaser, M. (eds.) (2018). A world of many worlds. Duke University Press.

de la Cadena, M. (2019). An invitation to live together: Making the “complex we.” Environmental Humanities 11 (2): 477–484. https://doi.org/10.1215/22011919-7754589.

Einbinder, N., Morales, H., Mier y Terán Giménez Cacho, M., Ferguson, B. G., Aldasoro, M. & Nigh, R. (2022). Agroecology from the ground up: A critical analysis of sustainable soil management in the highlands of Guatemala. Agriculture & Human Values 39: 979–996. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-022-10299-1.

Falkowski, T. B., Chankin, A., Diemont, S. A. W. & Pedian R. W. (2019). More than just corn and calories: A comprehensive assessment of the yield and nutritional content of a traditional lacandon Maya milpa. Food Security. 11, 389–404. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12571-019-00901-6.

Figueroa-Helland, L. E. (2012). Indigenous philosophy and world politics. PhD Dissertation. Arizona State University. https://hdl.handle.net/2286/R.I.15065.

Figueroa-Helland, L. E., Thomas, C. & Aguilera, A. (2018). Decolonizing food systems: Food sovereignty, indigenous revitalization, and agroecology as counter-hegemonic movements. Perspectives on Global Development and Technology 17(1–2): 173–201. https://doi.org/10.1163/15691497-12341473.

Fonteyne, S., Castillo Caamal, J. B., Lopez-Ridaura, S., Van Loon, J., Espidio Balbuena, J., Osorio Alcalá L., Martínez Hernández, F., Odjo, S. & Verhulst, N. (2023). Review of agronomic research on the milpa, the traditional polyculture system of Mesoamerica. Frontiers in Agronomy 5: 1115490. https://doi.org/10.3389/fagro.2023.1115490.

Ford, A. & Nigh, R. (2009). Origins of the Maya Forest Garden: Maya Resource Management. Journal of Ethnobiology 29(2): 213–236. https://doi.org/10.2993/0278-0771-29.2.21329.2.213.

Ford, A. & Nigh, R. (2015). The Maya forest garden: Eight millennia of sustainable cultivation in the tropical woodlands. Left Coast Press.

Ford, A., Turner, G. & Mai, H. (2023). Favored trees of the Maya milpa forest garden cycle. In L. Hufnagel (ed.) Ecotheology – Sustainability and religions of the world. IntechOpen. 10.5772/intechopen.106271.

Fox Tree, E. (2010). Global linguistics, Mayan languages, and the cultivation of autonomy. In M. Blaser, R. De Costa, D. McGregor, & W. D. Coleman (Eds). Indigenous peoples and autonomy: Insights for a global age. (Pp. 80-106). University of British Columbia Press.

Gargallo, F. (2012. Feminismos desde Abya Yala. Ediciones desde abajo.

Grandin, G. (2004). The last colonial massacre: Latin America in the Cold War. University of Chicago Press.

Gray, R. R. R. (2022). Rematriation: Ts’msyen law, rights of relationality, and protocols of return. Native American and Indigenous Studies 9(1): 1-27. https://doi.org/10.1353/nai.2022.0010.

Gudynas, E. (2011). Buen Vivir: Today’s tomorrow. Development 54 (4): 441–447. https://doi.org/10.1057/dev.2011.86.

Guzzon, F., Arandia Rios, L. W., Caviedes Cepeda, G. M., Céspedes Polo, M., Chavez Cabrera A., Muriel Figueroa J., Medina Hoyos, A. E., Jara Calvo, T. W., Molnar, T. L., Narro León, L. A. & Narro León, T. P. (2021). Conservation and use of Latin American maize diversity: Pillar of nutrition security and cultural heritage of humanity. Agronomy 11 (1): 172, 1-22. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy11010172.

Halvorsen, S. & Zaragocín, S. (2021). Territory and decolonisation: debates from the Global Souths. Third World Thematics 6 (4-6): 123-139. https://doi.org/10.1080/23802014.2022.2161618.

Haraway, D. (2013). SF: Science fiction, speculative fabulation, string figures, so far. Ada: A Journal of Gender, New Media, and Technology 3: 1-18. https://hdl.handle.net/1794/26308.

Haraway, D. (2016). Staying with the trouble: Making kin in the Chthulucene. Duke University Press.

Heidbrink, L., Batz, G. & Sánchez, C. (2021). “Why would anyone leave?”: Development, overindebtedness, and migration in Guatemala. Maya America: Journal of Essays, Commentary, and Analysis 3(3): 194–207. https://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/mayaamerica/vol3/iss3/1.

Heindorf, C. Reyes-Agüero, J.A. & van’t Hooft, A. (2021. Local Markets: Agrobiodiversity reservoirs and access points for farmers’ plant propagation materials. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems. 5: 597822. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsufs.2021.597822.

Holt-Giménez, E. (2006). Campesinx a campesinx: Voices from Latin America’s farmer to farmer movement for sustainable agriculture. Food First Books.

Horst, O. (1989). The persistence of Milpa agriculture in highland Guatemala. Journal of Cultural Geography 9 (2): 13–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/08873638909478460.

Islebe, G. A., Torrescano-Valle, N., Valdez-Hernández, M., Carrillo-Bastos, A. & Aragón-Moreno, A. A. (2022). Maize and ancient Maya droughts. Scientific Reports 12, 22272: 1-11. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-26761-3.

Kamal, A. G., Linklater, R., Thompson, S., Dipple, J. & Ithinto Mechisowin Committee. (2015). A recipe for change: reclamation of Indigenous food sovereignty in O-Pipon-Na-Piwin Cree Nation for decolonization, resource sharing, and cultural restoration. Globalizations 12(4): 559-575. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14747731.2015.1039761.

Lachniet, M. S. (2004). Late Quaternary glaciation of Costa Rica and Guatemala, Central America. Geological Society of America Bulletin 114(5): 547-558. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1571-0866(04)80118-0.

Latin American Studies Association (LASA). (2024). Rajawal or Nawal (Guardian Spirit, Protector). Accessed 4 April 2024. Available at: https://mayaspirituality.lasaweb.org/en/rajawal/.

Lope-Alzina, D. G. (2017). A conceptual approach to unveil homegardens as fields of social practice. Journal of Ethnobiology and Conservation 6(19): 1-16. https://doi.org/10.15451/ec2017-11-6.19-1-16.

Lopez-Ridaura, S., Barba-Escoto, L., Reyna, C. Hellin, J., Gerard, B. & van Wijk, M. (2019). Food security and agriculture in the Western Highlands of Guatemala. Food Security 11: 817–833. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12571-019-00940-z.

Lopez-Ridaura, S., Barba-Escoto, L., Reyna-Ramirez, C. A., Sum, C., Palacios-Rojas, N. & Gerard, B. (2021). Maize intercropping in the milpa system. diversity, extent and importance for nutritional security in the Western highlands of Guatemala. Scientific Reports 11(1): 3696. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-82784-2.

Martens, T., Cidro, J., Hart, M. A. & McLachlan, S. (2016). Understanding Indigenous food sovereignty through an Indigenous research paradigm. Journal of Indigenous Social Development 5: 18-37. https://journalhosting.ucalgary.ca/index.php/jisd/article/view/58469/43974.

May, T. (2021). Friends of the Lake? The Megacollector conflict and the vindication of Tz’unun Ya‘. PhD dissertation. Durham University. https://etheses.dur.ac.uk/14043/.

McCarthy, C., Shinjo, H., Hoshino, B. & Enkhjargal, E. (2018). Assessing local Indigenous knowledge and information sources on biodiversity, conservation and protected area management at Khuvsgol Lake National Park, Mongolia. Land 7(117): 1-11. https://doi.org/10.3390/land7040117.

Moreno-Calles, A. I., Casas, A., Rivero-Romero, A. D., Romero-Bautista, Y. A., Rangel-Landa, S., Fisher-Ortíz, R. A. & Santos-Fita, D. (2016). Ethnoagroforestry: Integration of biocultural diversity for food sovereignty in Mexico. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine 12 (1): 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13002-016-0127-6.

Morrison, D. (2011). Indigenous food sovereignty: a model for social learning, In H. Wittman, A. Desmarais, & N. Wiebe (Eds.). Food sovereignty in Canada: Creating just and sustainable food systems. (pp. 253- 271). Fernwood Publishing.

Myers, N., Mittermeier, R. A., Mittermeier, C. G., Da Fonseca, G. A. & Kent, J. (2000). Biodiversity hotspots for conservation priorities. Nature 403: 853-858. https://doi.org/10.1038/35002501.

Nadasdy, P. (2003). Hunters and bureaucrat: Power, knowledge and Aboriginal-state relations in the Southwest Yukon. UBC press.

Nazarea, V. D. (2006) (orig. 1998). Cultural memory and biodiversity. Tucson: University of Arizona Press.

Patiño Niño, D.M. (2023). Critical Latin American feminisms: Community-based, experience-based, and gender-unraveling. Colombia Internacional 115: 175-200.

https://doi.org/10.7440/colombiaint115.2023.07.

Hugo Perales, R., Benz, B. F. & Brush, S. B. (2005). Maize diversity and ethnolinguistic diversity in Chiapas, Mexico. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 102(3): 949–954. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0408701102.

Hugo Perales, R., Brush, S. B. & Qualset, C. O. (2003). Dynamic management of maize landraces in Central Mexico. Economic Botany 57(1): 21–34. https://doi.org/10.1663/0013-0001(2003)057[0021:DMOMLI]2.0.CO;2.

Pinheiro-Barbosa, L. & Gómez-Sollano, M. (2014). La Educación Autónoma Zapatista en la formación de los sujetos de la educación: Otras epistemes, otros horizontes. Revista Intersticios De La Política Y De La Cultura. Intervenciones Latinoamericanas 3(6): 67–89. https://revistas.unc.edu.ar/index.php/intersticios/article/view/9065.

Praun, A., Calderón, C.I., Jerónimo, C., Reyna, J., Santos, I., León, R., Hogan, R., & Prado Córdova, J. P. (2017). Algunas evidencias de la perspectiva agroecológica como base para unos medios de vida resilientes en la sociedad campesina del occidente de Guatemala. Elikadura 21: El Futuro de la Alimentación y Retos de la Agricultura para el Siglo XXI: Debates sobre quién, cómo y con qué implicaciones sociales, económicas y ecológicas alimentará el mundo. Paper 23: 1- 32. https://www.eur.nl/sites/corporate/files/23_Prado.pdf.

Prado Córdova, J. P. (2021). A novel human-based nature-conservation paradigm in Guatemala paves the way for overcoming the metabolic rift. Capital & Class 45(1): 11–20.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0309816820929119.

Rosset, P., Val, V., Pinheiro-Barbosa, L., & Mccune, N. (2019). Agroecology and La Via Campesina II: Peasant agroecology schools and the formation of a sociohistorical and political subject. Agroecology and Sustainable Food Systems 43: 895- 914. https://doi.org/10.1080/21683565.2019.1617222.

Sanford, V. (2003). Buried Secrets: Truth and human rights in Guatemala. Palgrave Macmillan.

Simpson, L. B. (2014). Land as pedagogy: Nishnaabeg intelligence and rebellious transformation. Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society 3(3): 1-25. https://jps.library.utoronto.ca/index.php/des/article/view/22170/17985.

Steinberg, M. & Taylor, M. (2008). Guatemala’s Altos de Chiantla: Changes on the high frontier. Mountain Research and Development 28(3): 255-262. https://doi.org/10.1659/mrd.0891.

Strandby Andersen, U., Prado Córdova, J. P, Nielsen, U., Olsen, C., Nielsen, C., Sørensen, M. & Kollmann, J. (2008). Conservation through utilization: A case study of the vulnerable Abies guatemalensis in Guatemala. Oryx 42(2): 206-213. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0030605308007588.

Sweet, E. L. & Ortiz Escalante, S. (2017). Engaging Territorio Cuerpo-Tierra through body and community mapping: A methodology for making communities safer. Gender, Place & Culture. A Journal of Feminist Geography 24 (4): 594-606. https://doi.org/10.1080/0966369X.2016.1219325.

Todd, Z. (2016). An indigenous feminist’s take on the ontological turn: ‘Ontology’ is just another word for colonialism. Journal of Historical Sociology 29: 4–22. https://doi.org/10.1111/johs.12124.

Tuck, E. & Yang, K. W. (2012). Decolonization is not a metaphor. Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education, & Society 1(1): 1–40. https://jps.library.utoronto.ca/index.php/des/article/view/18630/15554

Tuck, E., McKenzie, M., & McCoy, K. (2014). Land education: Indigenous, post-colonial, and decolonizing perspectives on place and environmental education research. Environmental Education Research 20(1): 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2013.877708.

Tzul Tzul, G. (2018). Gobierno Comunal Indígena y Estado Guatemalteco. Guatemala: Ediciones Bizarras.

U.S. Customs and Border Protection. ([2024]). Nationwide Encounters. 22 March 2024. Accessed 4 April 2024. Available at: https://www.cbp.gov/newsroom/stats/nationwide-encounters.

Ulloa, A. (2016). Feminismos territoriales en América Latina: Defensas de la vida frente a lo extractivismos. Nómadas 45: 123-39. https://dx.doi.org/10.30578/nomadas.n45a8.

Universidad Ixil. (2021). Facebook post. 12 December 2021. Accessed 31 October 2023.https://www.facebook.com/UniversidadIxil/posts/pfbid0W6YSWWqFK2zDN6EtHVpWEbvymqWGZPccPXPr4RQAXnGGMtnF2rFaWamMf3SA9nEXl?locale=hi_IN.

van Etten, J. & de Bruin, S. (2007). Regional and local maize seed exchange and replacement in the western highlands of Guatemala. Plant Genetic Resources 5(2): 57–70. http://doi.org/10.1017/S147926210767230X.

van Etten, J., Fuentes López, M. R., Molina Monterroso, L. G. & Ponciano Samayoa Ponciano, K. M. (2008). Genetic diversity of maize (Zea mays L. ssp. mays) in communities of the western highlands of Guatemala: geographical patterns and processes. Genetic Resources & Crop Evolution 55: 303–317. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10722-007-9235-4.

Watts, V. (2013). Indigenous place-thought and agency amongst humans and non-humans (First Woman and Sky Woman go on a European Tour!). Decolonization, Indigeneity, Education and Society 2(1): 20–34. https://jps.library.utoronto.ca/index.php/des/article/view/19145/16234. Zaragocín, S. and Caretta, M.A. (2021). Cuerpo-Territorio: A decolonial feminist geographical method for the study of embodiment. Annals of the American Association of Geographers 111(5): 1503-1518. https://doi.org/10.1080/24694452.2020.1812370

[1] Boxbol is a traditional Ixil dish widely prepared in the Ixil Region. While ingredients vary, it typically consists of maize wrapped in squash or güisquil leaves, with toasted and ground squash seeds and a salsa from tomate de palo fruit.

[2] An abbreviation of Mercado Campesinx used hereafter.

[3] With this term, I adapt Indigenous theory on rematriation, specifically from Indigenous activism discourse as articulated by Ts’msyen scholar Robin R. R. Gray (2022), and Maya ontological perspectives that conceptualize the body-territory (Cabnal, 2010, 2017, 2019) with Earth’s body as a shared provider. According to Gray (2022, p.1-2) rematriation is “an Indigenous feminist paradigm, an embodied praxis of recovery and return, and a sociopolitical mode of resurgence and refusal. Indigenous laws and protocols are foundational to rematriation paradigms.”

[4] Watts (2013, p.23) describes ‘agency of place’ as conceptualized in Indigenous cosmologies with the notion of Place-Thought, in which human thought and identity are inseparable from the land, and caring for the land sustains the ability and capacity to think, act, and govern.

[5] Monika Banach and Elena Brito Herrera—partner of Pablo Ceto, rector and founder of the Universidad Ixil—define tiichajil as a term that “refers to freedom, peace, life without violence, conflicts or any type of discrimination or persecution, because of the defense of goods or life itself. Tiichajil is understood not only in an individual perspective, but also as the collective values of the community: harmony, equal opportunities, and the role that each person plays. These values are practiced as tiichajil tenam, where the word tenam refers to the community or the pueblo. An inherent element of this thinking is that well-being among all beings, human and other-than-human, is necessary for the collective experience to allow tiichajil tenam to occur.” (Banach & Brito Herrera, 2021, p.49-50).

[6] See also Lope-Alzina (2017) for analysis of the milpa, or home gardens, as a social practice.

[7] For more information on the Universidad Ixil performing decolonization in the region, see Batz (2021).

[8] This feminism is described as “a process of epistemic construction, is woven from the territory; from the body and its relationship with the land” (Gargallo, 2012, p.177, cited in Patiño Niño, 2023, p.2).

[9] ‘Body-earth territory’ refers to Indigenous ontologies, particularly those from knowledge traditions in Central America/Abya Yala, that emphasize the inseparability of nature and culture, and of the nonhuman and human worlds. I use the term rematriation to describe processes that acknowledge this reconnection between people and Earth’s soils, and living communities. The term also draws on the decolonial feminismo comunitario (communitary feminism) of Maya-Xinka activist and scholar Lorena Cabnal (2010, p.21), who calls for “the conscious recovery of our first territory: [the] body.”

[10] As Bridgewater and Rotherham (2019, p.301) note, biocultural protocols (BCPs) are developed through community consultations that define core values and customary laws, forming the basis for regulating access to traditional knowledge and resources.

[11] The term multispecies ethnography serves as an ontological marker denoting methods that move beyond the Cartesian nature/culture divide, an essential distinction for many Indigenous Peoples, including the Maya Ixil.

[12] Extractivism is defined after Gudynas’ work defining the term from the Latin American context as “the accelerated extraction of natural resources to satisfy a global demand for minerals and energy and to provide what national governments consider economic growth” (cited in Blaser & de la Cadena 2018, p.2).

[13] This volunteering was done with an Ixil grassroots organization that has shared seeds in the Ixil region since the early 1990s, a predominantly female Ixil collective whose work demonstrates the active use of campesinx-a-campesinx methods (Holt-Giménez, 2006) toward advancing Ixil food and seed sovereignty.

[14] To quote the words and analysis of Maya K’iche activist and sociologist Gladys Tzul Tzul (2018, p.72) on communal work, “in indigenous communities the social unit of exchange is communal work, which fulfills the function of regulating what is shared through the community.” Communal governance is “to govern life communally, to defend and preserve the concrete wealth produced by communal work” (ibid., 2018, p.35).

[15] The Spanish term used for ‘Planet Earth’ from Maya Ixil interlocutors.

[16] Complicating the singularity of the human, de la Cadena (2019, p.480, emphasis in original) writes that through the complex we, “‘we’ are multispecies. This ‘we’ confuses the requirements of the notion of ‘species’ conceived by Linnaeus and others as a category to classify mutually exclusive groups. Emerging from feminist reconceptualization, human and nonhuman can both include and exceed each other: becoming through relations”

[17] Or MIAF, for the abbreviation of the Spanish “Milpa Intercalada con Arboles Frutales” (“Milpa Intercropped with Fruit Trees”) (Cadena-Iñiguez et al., 2018; Fonteyne et al., 2023).

[18] Conclusions from Islebe et al. (2022, p.4) agree with Tuxill et al. that “maize was a famine breaker during drought periods. The geographical extension of droughts and their effect on tropical forests, and maize agriculture, is a key factor to understand how ancient Maya culture developed.”

[19] This study used the Land Equivalent Ratio (LER) for analysis.

[20] Seed exchange is shaped by networks of trust. In Guatemala, local exchanges occur mainly among family and neighbors, while regional flows involve traders, shopkeepers, or NGOs, where market access and seed innovation drive exchange (Hugo Perales et al., 2003, 2005; van Etten & De Bruin, 2007; van Etten et al., 2008). Acquiring seed through trusted social networks reduces uncertainty about quality and viability (Badstue et al., 2006, 2007).

[21] One cuerda is the rough equivalent to 0.108 acres (Horst, 1989, p.16).

[22] Fonteyne et al. (2023) note that the high labor demands of the milpa are among the main reasons farmers find these food systems difficult to maintain. Labor inputs range from 27 to 401 days per hectare per crop cycle, depending on management intensity and the number of years a field has been under cultivation. These figures are drawn from Table 1 in Fonteyne et al. (2023, p.10).

[23] In their review of the scientific literature on milpa agronomy, Fonteyne et al. (2023, p.05) cite Aguilar-Jiménez et al. (2011) and Caudillo Caudillo et al. (2006), who demonstrate that dense crop placement reduces the light, nutrients, and water available to unwanted plants, thereby promoting the growth of desired milpa species.

[24] ‘Farmer Fair.’

[25] A common reference system found for climate and general growing conditions among Ixil campesinxs.

[26] Suffix of ‘ita‘ or ‘ito‘ is added in Spanish to indicate something as small or an affective relationship.

[27] As Horst (1989, p.24) notes, however, the western highland varieties of maize are often preferred by these farmers for their better taste and texture. See also Guzzon et al. (2021).

[28] A variety of Cucurbita moschata with green inner flesh.

[29] A grass common in Guatemala (Family Poaceae, species Tripsacum laxum) used most often as animal feed.

[30] A plant from the amaranth family that grows commonly through self-establishment in the Ixil Region’s milpas.

[31] Phrasing from Christopher in multiple conversations from 2019.

[32] The literal meaning of Rajawal is “the owner, or the protector” but could also be understood as a soul or spirit companion (LASA [2024]).

[33] ‘Farmer School.’

[34] ‘social fabric’.

[35] ‘Board of Directors’.

[36] Referred to as caña, cane grass, but made likely of maguey, a native grass also used previously for men’s traditional bags (see Figure 8).

[37] D’Alesandro (2024) expands upon this term (see also Banach and Brito Herrera 2021, p.52) which could be understood broadly as reference to Ixil ancestral and cultural social norms.

[38] Citing Wies et al. (2022), Fonteyne et al. (2023, p.2) note that the use of chemical fertilizers, insecticides, or herbicides has little effect on maize productivity as they are often applied improperly. Osorio Alcalá and Fabián (2019, cited in Fonteyne et al., 2023, p. 7) find yields with maize increasing with synthetic fertilizers, beans not affected, and squash responding better to organic inputs. As is the case in Guatemala, fertilizer use is now common in milpas of Yucatán, Chiapas, and Puebla, Mexico (Mascorro De Loera et al., 2019; Espidio-Balbuena et al., 2020; Haas, 2021, cited in Fonteyne et al., 2023).

[39] “MAGA” is the Spanish acronym for Guatemala’s Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Food.

9 / December / 2025

By: Gina D'Alesandro

8 / November / 2025

By: Mariana Calcagni G

19 / September / 2025

By: Taylor Steelman

19 / September / 2025

By: Eva Navarro

14 / June / 2025

By: Sarah Steinegger, Nora Katharina Faltmann