December / 22 / 2025

By: Ankita Dutta

The looming ecological crisis demands an urgent rethinking of possibilities within our surroundings. This article examines the practice of bamboo-shoot fermentation in India’s North-Eastern Region (NER) and explores its connections to sustainability, food sovereignty, and the pressures of capitalist intervention. It traces how fermented foodways, while rooted in cultural knowledge, become entangled with globalised capitalist logics and emergent ‘glocal’ market spaces. Despite these legal and commercial mazes, the cultural teachings embedded in fermentation continue to offer vital pathways toward more sustainable futures.

food sovereignty, fermentation, identity, modernity, tradition, sustainability

“We talk about the process of fermentation these days, but people in the Northeast have been doing it forever” (Brar, 2017 in Fernandes, 2017, p.1)

Chef Ranveer Brar’s remark, which went viral on social media, momentarily brought visibility to India’s North-Eastern Region (NER) while also revealing mainland understandings of the place. The NER—comprising Assam, Arunachal Pradesh, Manipur, Meghalaya, Mizoram, Nagaland, Sikkim, and Tripura—represents a distinct geographic, cultural, political, and administrative entity. While geo-strategically significant, it remains one of Asia’s most militarized and politically volatile regions. Mainland discourses of the North-East, shaped by colonial records and perpetuated through contemporary media, tend to homogenize its diversity into a set of fixed stereotypes. Colonial writings cast the region as one needing “taming” (R. T. Gurdon, 1907/2000), while popular imagery continues to circulate derogatory labels such as “chinky” or “Chinese-looking” (Deb Barma, 2023). Within this context, food—particularly the practice of fermentation—entered the national imagination as both curiosity and a marker of difference. Yet, beyond this superficial encounter, fermentation opens a window into the region’s intricate and entangled histories of sustenance, adaptation, and belonging.

Across its diverse landscapes, Northeast India’s Indigenous communities have long practiced systems of seed preservation, plant use, and sustainable agriculture that move beyond the extractive “grow-and-take” models. These practices rely on locally available resources and knowledge(s) rather than external supply chains, making communities less vulnerable to external shocks and fostering localized food security—a cornerstone of food sovereignty. Traditional ecological knowledge encourages cooperation and reciprocity, from seed sharing to collective land use (Rechlin & Varuni, 2006), offering resilience that top-down development models often undermine. Here, the term Indigenous refers to the communities of the Northeast Indian region who self-identify as such, based on historical continuity with their ancestral lands and distinct trajectories from those of mainland India2.

Within this broader context, I highlight how the practice of fermenting bamboo shoots exemplifies generational knowledge and a sense of belonging. Beyond its scientific definition as a bioprocess in which microorganisms convert carbohydrates into alcohol or acid(Bauer, 2019), fermentation embodies traditional knowledge systems and memories of socio-cultural experiences. This skill—perfected by hand through carefully passed-down schemes of knowledge and adapted to environmental change—represents resilience rooted in local practice. This low-tech, cost-efficient method sustains communities not only nutritionally but also socially and spiritually. Historically, it served as a preservation technique and, at times, a substitute for salt when it was scarce. Unlike industrial canning, fermentation preserves and even enhances nutritional value (Vansintjan, 2019). In times of crisis, such community-led, small-scale practices go a long way in ensuring resilience and continuity.

As Katz (2021) argues, fermentation functions as a model for community-driven adaptation to climate change. Building and expanding on this insight, I show how resilient food practices—particularly fermentation and ingredient preservation—are deeply embedded within the lives of communities in Northeast India. I explore how these practices negotiate tension between ‘tradition’ and ‘modernity’, carving out spaces within modern frameworks of the market while resisting total commodification. What requires attention, however, is the unity of thought that binds these seemingly opposing forces—i.e. the traditional and the modern—when exploring connections between fermentation and food sovereignty, as articulated by La Via Campesina3. Given its sustainability and relevance to food security, fermentation provides a critical site to examine the intersections of ecology, economy, and identity. In a rapidly globalizing world shaped by capitalist and ‘glocal’ interventions, understanding how such practices endure—and what they reveal about sovereignty, autonomy, and adaptation—becomes crucial. Through the lens of political ecology, this article analyzes the braided nature of the fermentation practices in Northeast India, situating them within larger conversations of resilience, sovereignty, and the politics of food.

In Northeast India, bamboo is often referred to as the “Green Gold” because it is seen as an industrial raw material with the potential to bring economic prosperity (Sentinel Digital Desk, 2021). Bamboo is a versatile gift of nature that supports sustainable living through its varied uses. Unlike trees that take years to mature, bamboo can reach harvestable height in just three to five months (Farrugia & Goutham, 2021). This rapid growth makes it a highly renewable resource, easing pressure on forests and reducing deforestation. From beams and flooring to furniture, utensils, and even clothing, bamboo’s strength and flexibility make it a viable alternative to resource-intensive materials like steel and plastic. Its cultivation typically requires little water and fertilizer, which further reduces its environmental footprint. Bamboo cultivation and processing also thrive in rural areas, providing livelihoods and generating economic growth for local communities. In this way, it contributes to sustainable development while empowering marginalized populations.

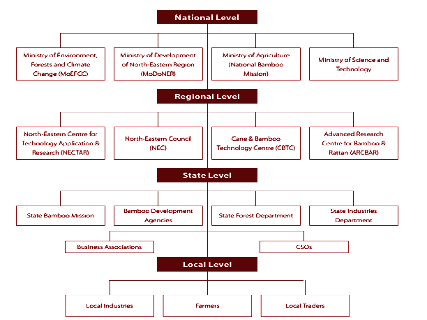

Recognizing the significance of the bamboo industry in the region, the North-Eastern Regional Bamboo Mission (NERBaM), launched by the North-East Council (NEC), was created to coordinate national bamboo policies and support state governments in developing strategies for bamboo production. Its framework, set out in “Bamboo-2022”, is organized as a 15-year program divided into three phases (International Bamboo and Rattan Organization, 2016). The chart below outlines the various stakeholders engaged in the process.

This network includes local industries, farmers, and local traders. Through state-specific action plans, one also sees recognition of traditional knowledge systems, including fermentation practices embedded in community life. Globally, and especially in developing countries, an estimated 0.8 billion people lack sufficient food to meet daily needs, while 2 billion suffer from malnutrition. Properly utilized, bamboo shoots can help address this challenge, offering not only nutrition but also opportunities for value-added economic activity at the entrepreneurial and community levels. In this light, the following section explores the linkages between fermentation and its role in sustaining food sovereignty. Oral traditions and generational knowledge of fermentation place communities at the center of production, reinforcing both their identity and their ways of life.

Fermentation and food sovereignty

The rising issue of food insecurity has a disproportionate impact on Indigenous communities (Jernigan et al., 2021). Food sovereignty resists corporate food regimes by prioritizing local and national economies, advancing sustainable models of consumption, and promoting health, equity, and cultural resilience in the face of corporate dominance. When neoliberal markets appropriate microbial processes, they undermine the sustainable lifeworlds in which these practices are rooted. The raw, sensuous vitality of fermentation is close to home, an expression of human-nature co-existence. Fermentation is not an imposition but an articulation of the intertwined processes of existence and survival. How fermentation practices across different regions of the world shape food sovereignty thus becomes a compelling field of inquiry.

Communities in various regions of Asia, South America, and Europe have long used fermentation to improve soil fertility (Betoret & Betoret, 2020, p.25-29). These practices enable high yields without reliance on commercial agrochemicals. By naturally preserving ingredients, fermentation reduces food spoilage at a time when hunger remains a pressing global issue. Linking fermentation to environment, health, and socio-economy, Quave and Pieroni (2023 [2014]) demonstrate how it reduces waste while strengthening food sovereignty among practicing communities. Across cultures, traditional knowledge guides microbial transformation in more ways than one.

Food sovereignty rests on the conviction that small farmers, drawing on traditional and Indigenous knowledge, are capable of producing food for their communities and feeding the world in sustainable and healthy ways. In this paper, I use the term food sovereignty to mean the right of stakeholders to determine the food systems of their region. Following the definition advanced by La Via Campesina, “culturally appropriate food systems” that draw on local resources and ingredients, while promoting and furthering locally available resources and ingredients for food production, all while putting people at the center, remain fundamental. What is needed is a context-specific model of food sovereignty, one that adapts to changing times rather than relying on rigid frameworks.

The interaction of sustainability and food sovereignty is thus an exciting arena of academic exploration. This article illuminates the traditional knowledge of bamboo shoot fermentation in the hills and plains of Northeastern India in all its vividness. It highlights both the historical significance of the practice and its continuing relevance in addressing present crises.

Alliances through the affective process of fermentation

Fermented food products have been produced and consumed by various ethnic communities for more than 2,500 years (Nath & Tiwari, 2022). Among these, the fermentation of bamboo shoots for consumption is a widespread practice across both hills and plains. In Assamese, it is called “Khorisa”. The preparation is a careful, personal, and intricate process. Bamboo shoots are collected—usually from kitchen gardens or community fields—and then finely chopped and pressed tightly into a hollow green bamboo stem. The tip of the vessel is sealed with bamboo leaves or other wild plants and left to ferment under anaerobic conditions for 7-15 days (Nath & Tiwari, 2022).

This effective process of fermentation, as argued earlier, has now entered larger market spaces while carving out its own sovereign presence. Fermented products fetch higher income due to their longer preservation, higher market price, and availability throughout the year. This motivates producers to engage with the capitalist maze while maintaining their own space of being. The “capitalist maze” refers to the intricacies of functioning within and entering a competitive framework. According to a 2003 report by the North-Eastern Council, a cost–return analysis showed annual net income of 23 million Indian rupees4 from these bamboo products, with Arunachal Pradesh earning the highest and Sikkim the lowest. Employment opportunities were also estimated: approximately 1,260 people per year could earn their subsistence from selling bamboo shoot products (Bhatt et al., 2005). This reflects the persistence of the traditional bamboo industry through its adaptation to modern spaces.

Anna Tsing, for instance, reveals, in her ethnography, how following Matsutake mushrooms “guides us to possibilities of coexistence within environmental disturbance” (Tsing, 2015, p.4). Building and expanding on her work, I argue that fermented bamboo shoots guide us to explore the possible alliances and fellowships in the current moment of crisis. Caring for fermenters requires deep knowledge of how to distinguish the fermented from the rotten. The capitalist notion of commodities as mundane objects erases the layered nature of traditional knowledge systems in more ways than one. The arrival of fermented foods in urban markets seems to symbolize the growing distance between consumers and creators—a reflection of the current crisis.

In the next section, I point to the complex interplay between the seemingly binary notions of modern and traditional, or old and new. I aim to show how each reshapes the other over time, and how persisting traditional knowledge is simultaneously transformed. Its transformation, once again, will be a value-laden process. How it impacts persistence must be understood in line with ground realities. With the market logic apparent and the state acting as facilitator, new markets have now emerged.

Along the path from field to plate, foodways are increasingly shaped by market logic. The crisis lies in the exploitation of the producers and the appropriation of surplus labor. What Marx described as alienation from the product of labor in his work on “estranged labor” is the dark side that capitalism introduces (Marx, 1964). This detachment creates a metabolic rift in what Marx, through his conception of homo-faber, saw as the creative, natural process of labor (Bartelt, 2022). In this context, work becomes an exchange between employer and employee, stripped of human essence. It becomes a necessity for survival. Foster and Clark, in their work on “ecological imperialism”, link this rift—born with private property and capitalism—to ecological implications (Foster & Clark [2009], in Vasan, 2018, p.278). Yet, this view of capitalism as all-encompassing overlooks how local realities negotiate space within the seemingly uniform whole. Sudha Vasan (2018) argues that such a framing negates alternative realities rooted in the local contexts. The need, then, is to adopt a different lens—one that recognizes the layers of negotiation and identity shaping sovereignty within the global.

Deka et al. (2023), in “Seeds and Food Sovereignty”, describe the lived experiences of food sovereignty and seed saving on the ground. They raise questions about “new food systems” and “new relations” emerging within what I call “indigenous spaces of sovereignty”. Examples such as strawberry farming and the rise of start-ups illustrate the layered entanglements of capitalist structures and community agency. The authors show how capitalist subjectivities creep into spaces of aspirations, gaining acceptance in veiled forms and drawing us into the complex maze we inhabit. One statement in the book that caught my attention was the romanticism embedded in the theoretical advice given to the farmers regarding seed conservation (Deka et al., 2023, p.57). I argue that Indigenous farmers depend on market demand: they produce what society wants. Seed conservation, therefore, requires a parallel consumer base willing to buy those varieties of ethnic seeds and produce. In the current economy, such demand would incentivize producers and attract new entrants into the field.

In this light, market intervention does not always encroach upon sovereignty. It can also enable and promote sovereignty in new ways of being and acting. Various NGOs and start-ups now use traditional fermentation technologies to carve out their “indigenous spaces of sovereignty” within the market system. The Indian Council for Agricultural Research also supports these practices, empowering traditional knowledge and innovation in community practices such as fermentation (ICAR, n.d.). Such institutional mechanisms shape how local practices mark their presence in the global economy. This interplay between local and global has been theorized as glocalization.

“Glocalization” offers a useful lens for understanding new markets in the global world. Robertson (1995), for instance, critiques globalization theories for their homogenizing tendencies. The term “glocal” initially referred to how global business models adapted goods to local tastes. He, however, analyzes global-local problem as a process of simultaneous interpenetration (Robertson, 1995). Rather than seeing globalization as dominating local tendencies, he emphasizes how interaction produces new forms of functioning. The local, in this view, is an active force that negotiates with the global in a “mutually implicative” stance (Robertson, 1995, p.27). This helps us understand the evolving markets for fermented bamboo shoots.

An article in Vogue highlights the worldwide spread of fermentation through market linkages (Ved, 2019). Restaurants and cafés such as Mumbai’s Olive Bar and Kitchen, and Delhi’s Greenr Cafe and FabCafe now organize workshops teaching beginners the basics of brewing kombucha and kefir. Linking this to my focus on fermented bamboo shoots, I recall living in Delhi for nearly five years, where the homely smell in certain pockets of the metropolis would momentarily take me back to my roots. Areas like Munirka and Majnu-ka-Tilla sell fermented bamboo shoots and other indigenous ingredients, carrying them from the field to our plates.

Various online small businesses have also emerged. One example is the Meghalaya-based “The Northeast Store“, whose tagline reads: “Discover unique and authentic northeastern products with us— from food items to handicrafts and handlooms, all handcrafted by local artisans and producers. Support local livelihoods by purchasing from us and help preserve the region’s rich culture and heritage“. Even global e-commerce sites like Amazon now provide space for indigenous. One product description for bamboo shoots reads, “Direct from Kwatha village of Manipur, we present to you Fermented Bamboo Shoot, locally known as Soibum“5. These products are promoted through the online media and capitalist market networks. Yet, the stronghold of the producers and promoters is evident, carving a novel space within the global to reinstate their sovereignty. This reflects a sovereign negotiation with the market system, where exploitative appropriation is resisted through the uniqueness of the practice and community control over the process. With the rise of small businesses and e-commerce, however, producers increasingly retain agency, directly selling to consumers. Alongside community efforts at maintaining their agency in pricing and production till distribution and consumption, the state has also taken up facilitatory steps. The Minimum Support Price (MSP) is intended by the central government to prevent exploitation, though anomalies in its implementation often persist. Thus, there remains a need to create new spaces and understandings of sovereignty within the capitalist mazes of production and consumption.

The release of Kurkure’s6 ‘NorthEast Special’ flavor lists rice as one of its ingredients. The ways in which large corporations leverage the flavors and emotions associated with a region’s food reveal how capitalism engages with food cultures and identities to serve profit motives. It is questionable how far such products genuinely cater to the needs of the communities or regions they claim to represent. The inclusion of bamboo shoots in menus representing the region, equating them with the Northeastern palate, reflects a strategic use of community emotions in the market. The distinctive smell and taste of bamboo shoots function as a culinary “shibboleth”, acting as a cultural marker for the group (Brumberg-Kraus & Dyer, 2011). Using bamboo shoots as a homogenized symbol for Northeastern India oversimplifies the rich diversity of preparation methods and fermentation technologies across communities. However, this does not erase the niche spaces where local-global negotiations are evident. Communities’ aspirations often embrace multiple pathways simultaneously, refusing to be constrained by either-or notions of modernity.

Against such reductive binaries, I propose acknowledging the coexistence and integration of diverse elements. Food sovereignty provides a useful lens to explore this phenomenon, particularly in online spaces claimed by start-ups and local entrepreneurs to promote traditional cuisines. The convergence of modern online tools with creative promotion of indigenous food reflects a creative amalgamation. The rise of local business stores on Instagram, Facebook, and other platforms demonstrates that, while merged with global systems, communities still assert their roots. Arjun Appadurai (1996) speaks to this, emphasizing that modernity is not a single, linear path. Instead, it emerges and reshapes itself according to diverse socio-cultural and geographical contexts, moving beyond simple binaries such as tradition versus modernity, culture versus power, or local versus global (Appadurai, 1996).

Building on this perspective, Gibson-Graham et al. (2013) propose the idea of the iceberg economy, which acknowledges hidden economic diversity beyond mainstream frameworks, offering a richer understanding of how economies function in all their intricacies (Gibson-Graham et al., 2013). Similarly, Rajni Bakshi (2020) advocates for a degrowth discourse, which shifts focus from growth-driven development to strategies that generate social, material, and ecological well-being. In doing so, she emphasizes that localization strengthens complex connections rather than isolating communities (Bakshi, 2020, p.45-53).

This view of emerging markets offers a holistic understanding of how locales negotiate with capitalist forces. Sudha Vasan (2018) emphasizes the ecological crisis and its linkages with capital. She argues that addressing the current crisis requires examining the economic system of capitalism itself. This article highlights ways communities negotiate with capitalism, presenting an amalgamation of forces in new ways of being.

Community efforts establish meaningful connections with capitalist forces while simultaneously rooting and expanding identities through fermentation. The oral histories of community recipes bind members together in multiple ways—especially women, who serve as guardians of a fading knowledge system that demands recognition. At a time when many young people leave in search of better opportunities, their connection to the land endures through memories of food and shared culinary knowledge.

“As anxious dreams and uncertain futures linger, the taste of foreign food and ingredients carried from home creates new affections and connections with the land and villages that indigenous migrants have left behind” (Kikon & Karlsson, 2019, p.98)

The Lotha community7 call themselves “Rhuchon etsoi‘, meaning fermented bamboo-shoot eaters, highlighting how identity is shaped by distinct consumption cultures (Vohra, 2022). Small-scale fermentation practices become defining markers of Indigenous and tribal food. The contrast between such foods being described as smelling like ‘shit’ (Kikon, 2021, p.288) and simultaneously promoted in tourist hubs across the nation is striking. The film ‘Axone’ vividly portrays the struggles of Indigenous migrants within their own country, illuminating diverse food practices and sensory experiences (Kharkongor, 2019). As people migrate, community food practices travel with them, linking food, mobility, and evolving notions of modernity.

Seno Tsuhah, an Indigenous social activist from the Chakhesang Naga community in Chizami, is widely recognized in Northeast India for her work in sustainable farming (Deka et al., 2023, p.22). She speaks of ‘shared sovereignty‘—a form of food sovereignty built on sharing seeds, knowledge, and mutual support in managing land and resources. Shared sovereignty represents a vision for the future, shaping how communities imagine collective well-being. This model underscores the importance of shared knowledge: the community must remember what it already knows and pass these memories to younger generations, treating this responsibility with full seriousness of being and acting. Promoting active citizenship through reconnection with traditional food practices can be a starting point. It is imperative to revisit our roots, reflect on daily practices, and initiate conversations about food to ensure these traditions endure. Food and memory of the land are intertwined. Reconnecting with traditional foodways is vital for sustaining the region and for nurturing small, resilient, and sustainable lifeworlds in the face of the raging climate crisis.

The exploration of fermentation, food sovereignty, and sustainability in the region reveals a critical crossroads where the political and ecological realms intersect. Examining the interplay of capitalism and food sovereignty highlights both the potential threats and possibilities for traditional and Indigenous knowledge systems. Yet, amidst these challenges, hope emerges through the rediscovery, revitalization, and innovation of these systems.

The rise of seed libraries, the resurgence of ethnic cuisines in urban spaces, and interdisciplinary interest in traditional foodways signal a collective awakening. This suggests that solutions to ecological crises may lie not only in new technologies, but also in the wisdom embedded within ancestral practices. Traditional fermentation techniques, rooted in local knowledge and resources, offer a compelling example of this potential.

However, our fleeting forgetfulness of this knowledge deepens the ecological crisis. Our focus, then, must shift toward bridging the gap between traditional home knowledge and contemporary scientific understanding. Interdisciplinary conversations around traditional fermentation, facilitated by rising consumer interest, can spark meaningful innovations. This paper serves as a starting point, acknowledging the need for further research into this fertile ground.

As we move forward, it is imperative to recognize that our role is not one of mere inheritance, but of responsible custodianship. We borrow this land, with its rich tapestry of fermented traditions, not for fleeting consumption but for future generations. By nurturing this microbial-human co-existence, we might pave the way for a more sustainable and fermented future—one where tradition and innovation together nourish the land and its people.

The paper was written as part of my course requirements in the optional course of Political Ecology of Northeast India offered by the Special Centre for the Study of North East India, Jawaharlal Nehru University. I want to thank my course instructors, Prof. Rakhee Bhattacharjee and Dr. G Amarjit Sharma. I would also forward my gratitude to my PhD supervisor, Dr. Obja Borah Hazarika, for her constant support and guidance during the process of this submission. I thank the reviewers of the paper for their valuable suggestions, and Meenakshi Nair Ambujam for her constant aid and advice throughout the process of editing this paper.

Appadurai, A. (1996). Modernity at large: Cultural dimensions of globalization. University of Minnesota Press.

Bakshi, R. (2020). For an alternative paradigm of development. In Kalshian, R., & S. Weiss (Eds.), Investigating Infrastructure: Ecology, Sustainability and Society (pp. 45-53). Heinrich Böll Stiftung.

Bartelt, P. (2022). Marx, prayer, and humanity. 1517. Retrieved June 21, 2024, from https://www.1517.org/articles/marx-prayer-and-humanity

Baruah, S. (2024). When civilizational nationalism meets subnationalism: The crisis in Manipur. Studies in Indian Politics, 12(1), 8-19. https://doi.org/10.1177/23210230241235360

Bauer, D. (2019, April 30). How fermentation makes food delicious. Cravings of a Food Scientist. Retrieved on May 13, 2023, from https://cravingsofafoodscientist.com/2019/04/30/how-fermentation-makes-food-delicious/

Betoret, N., & Betoret, E. (Eds.). (2020). Sustainability of the food system: Sovereignty, waste, and nutrients bioavailability. Academic Press. https://www.sciencedirect.com/book/edited-volume/9780128182932/sustainability-of-the-food-system#editors

Bhatt, B. P., Singha, L. B., Sachan, M. S., & Singh, K. (2005). Commercial edible bamboo species of the North-Eastern Himalayan Region, India. Part II: Fermented, roasted and boiled bamboo shoots sales. Journal of Bamboo and Rattan, 4(1), 13-31.

Brumberg-Kraus, J., & Dyer, B. D. (2011). Cultures and cultures: Fermented foods as culinary ‘shibboleths’. In Saberi, H. (Ed.), Cured, fermented and smoked foods: Proceedings of the Oxford symposium on food and cookery 2010 (pp. 56-65). Prospect Books.

Deb Barma, A. (2023, March 18). Stereotyping Northeast Indians in mainstream media: An unfair and harmful representation. Times of India. Retrieved on September 18, 2024, from https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/readersblog/if-only-i-can-speak/stereotyping-northeast-indians-in-mainstream-media-an-unfair-and-harmful-representation-51594/

Deka, D., Rodrigues, J., Kikon, D., Karlsson, B. G., Barbora, S., & Tula, M. (2023). Seeds and Food Sovereignty: Eastern Himalayan Experiences. North Eastern Social Research Centre.

Farrugia, M., & Goutham, S. (2021, April 16). The ultimate guide to sustainable bamboo harvesting: Tips and best practices. Bamboo U. Retrieved on January 30, 2024, from https://bamboou.com/your-go-to-guide-for-harvesting-bamboo-sustainably/

Fernandes, S. M. (2017, June 8). Everything we fascinate about, North-East has been doing it: Ranveer Brar. The Times of India. Retrieved September 28, 2025, from https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/bengaluru/everything-we-fascinate-about-north-east-has-been-doing-it-ranveer-brar/articleshow/59035086.cms

Gibson-Graham, J. K., Cameron, J., & Healy, S. (2013). Take back the economy: an ethical guide for transforming our communities. University of Minnesota Press. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5749/j.ctt32bcgj

Gohain, S. (2021). Relative indigeneity in Northeast India. Beyond Myths: A symposium on anthropological histories of tribal worlds. Retrieved on September 28, 2025, from https://www.india-seminar.com/2021/740/740_swargajyoti_gohain.htm

ICAR. (n.d.). Agri-Kaleidoscope: Practices unique to Nagaland. KIRAN Empowering Agricultural Knowledge and Innovation in North East. Retrieved on June 27, 2024, from https://kiran.nic.in/nagaland.html

International Bamboo and Rattan Organisation. (2016). Desk Study on the Bamboo Sector in North-East India. International Bamboo and Rattan Organisation.

Jernigan, V.B.B., Maudrie, T. L., Nikolaus, C. J., Benally, T., Johnson, S., Teague, T., Mayes, M., Jacob, T., & Taniguchi, T. (2021). Food sovereignty indicators for indigenous community capacity building and health. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems, 5, 1-9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsufs.2021.704750

Katz, S. E. (2021). Sandor Katz’s fermentation journeys: Recipes, techniques, and traditions from around the world. Chelsea Green Publishing UK.

Kharkongor, N. (Director). (2019). Axone [Film]. Yoodlee Films.

Kikon, D., & Karlsson, B. G. (2019). Leaving the Land: Indigenous Migration and Affective Labour in India. Cambridge University Press.

Kikon, D. (2021). Dirty food: racism and casteism in India. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 45(2), 278-297. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2021.1964558

La Via Campesina. (2003, January 15). Food sovereignty: Explained. La Via Campesina. Retrieved on January 30, 2024, from https://viacampesina.org/en/food-sovereignty/

Marx, K. (1964). Economic and philosophic manuscripts of 1844 (D. J. Struik, Ed.). International Publishers.

Nath, P. C., Tiwari, A. (2022). Comparative studies on the ethnic fermented food products and its preservation methods with special focus on North-East India. Journal of Ecology & Natural Resources, 6(4), 1-18. https://doi.org/10.23880/jenr-16000319

Quave, C. L., & Pieroni, A. (2023 [2014]). Fermented foods for food security and food sovereignty in the Balkans: A case study of the Gorani people of Northeastern Albania. Journal of Ethnobiology, 34(1), 28-43. https://doi.org/10.2993/0278-0771-34.1.28

R. T. Gurdon, P. (2000 [1907]). The Khasis. Alpha Editions.

Rechlin, M. A., & Varuni, V. (2006). A passion for pine: Forest conservation practices of the Apatani people of Arunachal Pradesh. Himalaya: The Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies, 26(1). 19-24. https://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/himalaya/vol26/iss1/7

Robertson, R. (1995). Glocalization: Time-space and homogeneity-heterogeneity. In Featherstone, M., Lash,S., & Robertson, R. (Eds.), Global modernities (pp. 25-44). SAGE Publications.

Sentinel Digital Desk. (2021, January 30). Bamboo the ‘green gold’ of North-East. The Sentinel Assam. Retrieved on May 13, 2023, from https://www.sentinelassam.com/north-east-india-news/bamboo-the-green-gold-of-north-east-522723

Tsing, A. L. (2015). The mushroom at the end of the world: On the possibility of life in capitalist ruins. Princeton University Press.

Vansintjan, A. (2019, January 18). Fermentation is back: How will living organisms reshape your plate? The Guardian. Retrieved on January 30, 2024, from https://www.theguardian.com/food/2019/jan/18/fermentation-food-how-to-process-ethics

Vasan, S. (2018). Ecological Crisis and the Logic of Capital. Sociological Bulletin, 67(3), 275-289. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038022918796382

Ved, S. (2019 , June 12). Why fermentation has become the new buzzword in the food industry. Vogue India. Retrieved on May 24, 2023, from https://www.vogue.in/culture-and-living/content/why-fermentation-has-become-the-new-buzzword-in-the-food-industry

Vohra, T. (2022, September 14). Fermentation allows me to slow down, and pay attention to the smallest of details. The Locavore. Retrieved on May 13, 2023, from https://thelocavore.in/2022/09/14/fermentation-allows-me-to-slow-down-and-pay-attention-to-the-smallest-of-details/

2 In Northeast India, the meaning of ‘indigeneity’ is primarily rooted in the sense of ‘belonging’ to a specific place or region (Baruah, 2024, p.13). Also, see Swargajyoti Gohain’s paper on ‘Relative Indigeneity’ (Gohain, 2021).

3 Food sovereignty is the peoples’, Countries’ or State Unions’ right to define their agricultural and food policy, without any dumping vis-à-vis third countries (La Via Campesina, 2003).

4 23 million INR is equivalent to 259,118.43 USD as per 24 September 2025 rate of exchange.

5 This product description features in the product‘s [Chingtam Kwatha Soibum Areeba – Fermented Bamboo Shoot 250 GMS (Vacuum Packed)] Amazon listing, accessible here: https://www.amazon.in/Chingtam-Soibum-Fermented-Bamboo-Shoot/dp/B08XZ8ZZ1Y

6 Brand of spiced, crunchy puffcorn snacks made of rice, lentil, and corn

7 The Lotha community, also known as Kyongs, are a vibrant and rich indigenous Naga ethnic group primarily residing in the Wokha district of Nagaland, India.

9 / December / 2025

By: Gina D'Alesandro

8 / November / 2025

By: Mariana Calcagni G

19 / September / 2025

By: Taylor Steelman

19 / September / 2025

By: Eva Navarro

14 / June / 2025

By: Sarah Steinegger, Nora Katharina Faltmann