December / 9 / 2025

By: Claudiu E. Nedelciu, Jennifer B. Hinton, Maartje T. Oostdijk, Kenza Benabderrazik, and Laura G. Elsler

(Introduction to the Special Issue on Post-growth food systems for a just social-ecological transition within Planetary Boundaries)

The special issue Post-growth food systems for a just social-ecological transition within Planetary Boundaries explores post-growth and degrowth approaches that advocate for sufficiency, care, regeneration, and the democratization of food systems. It shows that post-growth food initiatives face multiple structural barriers, including capitalist systems that prioritize profit over ecological and social well-being, colonial legacies that affect land access and cultural resilience, patriarchal regimes that undervalue care and regeneration, and dominant Western knowledge systems that dismiss and devalorize relational and experiential ways of knowing. Despite these barriers, there are seeds of hope. What emerges from the special issue is the importance of building alliances, fostering critical food systems literacy, and embracing artistic and culturally rooted practices to reimagine our relationships with food, land, and each other. We argue that there is a need to support diverse methodologies and (re)center marginalized perspectives in academia. A meaningful and extensive conversation around science-making and the societal relevance of academia in transforming food systems is long overdue.

Food systems transformation, post-growth, social-ecological transformation, degrowth, knowledge systems

Dominant global food systems today remain deeply entrenched in an extractive, growth-oriented path, cemented through state subsidies, international trade laws, and capitalist logic (Neo & Emel, 2017). The current structure and operationalization of the global food system are among the major contributors to climate change, ecological degradation, and rural decline (Campbell et al., 2017), making it a key contributor to the transgression of several Planetary Boundaries (Richardson & Christensen, 2025). With its focus on delivering economic growth and financial gain, the global food system is locked into a path dependency of chasing ever-larger yields. This translates into an increasing use of chemical inputs (e.g., pesticides and synthetic fertilizers), industrial farming or fishing techniques that farm ecosystems (e.g., bottom trawling, monocultures, excessive tillage), and energy-intensive technologies (e.g., heavy machinery and AI). In response to the dire social and ecological impacts of this system, recent scholarship stresses the need to move away from analytical, sector-focused, and technology-centered approaches to food systems and instead focus on transforming the broader socio-economic contexts within which food systems operate (Feola, 2025; Gibson et al., 2025). Specifically, scholars highlight the need for degrowth or post-growth transformations, which entail reconceptualizing human food metabolisms according to values, food practices, and lifestyles that strive for sufficiency over efficiency, regeneration over extraction, distribution over accumulation, commons over private ownership, and care over control (McGreevy et al., 2022).

The main aim of post-growth approaches is to ensure that everyone’s needs are equitably met within the ecological limits of our finite planet (Kallis et al., 2025). This field highlights the importance of inclusive, participatory approaches rooted in local knowledge and calls for the emancipation of the imaginary to break free from the dominance of capitalist logics that prioritize economic growth at all costs (Parrique 2019; Latouche 2003). A post-growth transformation of food systems would involve not only the active involvement of historically marginalized communities, including Indigenous peoples, women, youth, minorities, and small-scale producers. It also implies engaging with non-dualist ontologies to broaden the spectrum of possible transformations in the food systems (see Escobar 2015; Escobar et al., 2024). Democratizing food systems and embracing a plurality of paradigms and knowledge systems are therefore key components of post-growth transformations, which contrasts with a global food system that remains deeply entrenched in dualism and growth-oriented logics.

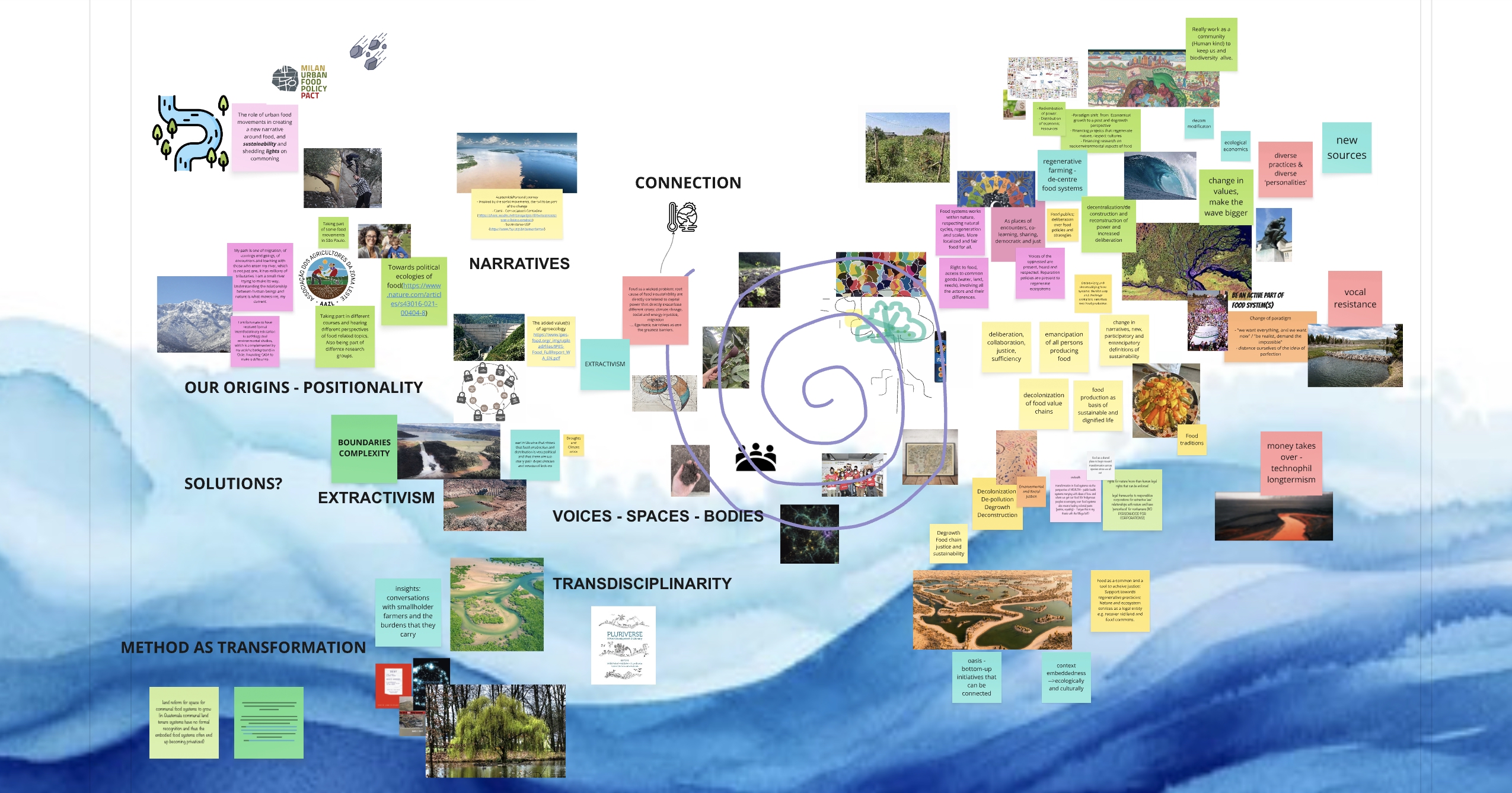

This special issue explores precisely these ancestral and emerging perspectives on post-growth transformations of food systems, which call for a fundamental rethinking of how we cultivate, share, and relate to food. In the editorial team, we curated a diverse collection of contributions from both academic and non-academic voices, with diverse representation from across the world. The intersection of our diverse professional backgrounds, origins, and demographics (among other dimensions) has given us experiences of systemic marginalization and privilege that shape our perspectives. We recognize that we carry biases that may reinforce dominant worldviews, which we try to counter with reflexivity and humility. It also requires stepping back and providing a space for others. This special issue is an attempt at providing such a space. While we have succeeded in some areas, it is imperfect in others.

We also wanted to challenge the current publishing norms and practices by offering alternatives. The editorial process prioritized inclusivity, care, and deliberation over speed and output. Rather than adhering to the impersonal, profit-driven standards typical of mainstream academic publishing, the special issue was conceived as a collaborative, evolving endeavor. It aimed not only to foster a sense of belonging among contributors but also to inspire future scholarly and practical offshoots rooted in post-growth thinking.

At a time when alternative views and diversity are confronted with increased hostility in academia and society—particularly in the West—we believe that initiatives such as this collection are even more important in creating disruptive spaces for post-growth narrative and realities. Scientific voices that challenge hegemonic paradigms, including growthism and imperialism, are particularly marginalized. This takes shape not only through rhetorical delegitimization but also through structural mechanisms such as limited access to funding, defunding, and conventional performance-based evaluation systems. These pressures reinforce an output-driven “academic treadmill” culture (Smith, 2010) that prioritizes short-term deliverables, marketable results, and alignment with policy or corporate agendas, often at the expense of critical, interdisciplinary, and transformative inquiry. While such patterns have been observed for several decades (see Said, 1994), recent years have brought worrying, reinforcing dynamics. As funding becomes more precarious and tied to narrow metrics of impact and what Shore and Wright (2024) have called an “audit culture”, academics face growing constraints in pursuing research that questions capitalistic norms or engages with marginalized perspectives. The present collection is an answer to calls for reshaping academic publishing by restoring its societal relevance and purpose (see, for example, Elbanna & Child, 2023).

Initiating a special issue in a peer-reviewed journal reflects a belief that science can serve as a powerful tool to address societal crises. It can bring forward ideas, observations, and narratives that meaningfully contribute to building knowledge for systemic shifts and transformations. At the same time, history has shown that when science claims a monopoly on truth or becomes disconnected from societal needs and political positioning, it can lead to disastrous consequences. For example, the Green Revolution, beginning in the 1950s, introduced scientific innovations such as high-yield crops and synthetic inputs, which were seen as breakthroughs in food production. These were also regarded as the cutting edge for food system transformation. However, the obsession with maximizing yields sidelined traditional farming knowledge and marginalized small-scale farmers, especially in the Global South (Shiva, 1991). In the long term, it contributed to land dispossession, soil degradation, and dependency on costly technologies and harmful agro-chemical inputs (Patel, 2012), a process that continues today.

To prevent the monopolization of science, it is essential to reposition science-making within a global framework that prioritizes responsiveness to community needs and lived realities, and which acknowledges and challenges power asymmetries (Jacobi et al., 2021; Patel, 2025). As Brock et al. (2024) emphasize, “Diverse forms of evidence, knowledge, and expertise, including lived experience and traditional knowledge as well as case studies, scientific analyses, and peer-reviewed literature, need to be treated equally and centered in efforts to transform food systems.” Thus, engaging collaboratively with diverse food system practitioners such as farmers, activists, cooks, community facilitators, and cooperatives enables the recognition and integration of multiple ontologies and epistemologies, thereby enriching the landscape of knowledge production.

For this reason, we in the editorial team made a conscious decision to step outside the dominant growth-based food paradigm. With this special issue, we aimed to create a space for diverse voices, knowledge systems, narratives, and forms of expertise that support the transformation of our agricultural and food systems. We chose the Grassroots section of the Journal of Political Ecology because it offers a platform for environmental activists and scholars. As a not-for-profit, open-access journal, it aligned with our values of justice, accessibility, and solidarity. This special issue brings together a diverse group of authors whose work challenges dominant paradigms of food, knowledge, and power. Their case studies are not only empirical contributions—some of them are acts of epistemic resistance. They foreground worldviews rooted in indigenous knowledges, feminist resistance, everyday collaborative practices, and community-based struggles. They speak from and with the margins, offering a glimpse of food systems that are relational, regenerative, and just.

Grassroots also welcomes submissions in a variety of formats. In this spirit, we invited contributors to explore diverse formats. The special issue includes several artistic contributions. At this critical moment—when many of these knowledge systems remain marginalized and the debate around transformation is more urgent than ever—there is a need for broader interactions. These must go beyond exchanges among economists, scientists, engineers, and technocratic food system stakeholders and include meaningful dialogue with society through creative and inclusive bridges. Creativity, in this context, allows us to forge new imaginaries and co-develop narratives through storytelling, visualization, and embodiment. Engaging cognitive, emotional, and embodied knowledges in agroecology can emerge not only through farming practices but all throughout the process of sharing, cooking, eating, and valorizing waste. Creative practices become a medium for experimenting with, understanding, and carrying forward transformational dynamics while building stronger links with social movements.

Several studies in the special issue focus on indigenous food systems and their values. Kesselman and Zukulu (2025) show how the Amadiba community in South Africa follows foodways based on interconnection, gratitude, and collective responsibility. These are values that actively push back against extractive development, and are not limited to action in food systems, but re-emerge in resistance against highway development or plans for oil extraction. Rousell and Kesselman (2024) contribute a powerful visual essay that adds to this story, showing, in a nutshell, how colonialism has been oppressing indigenous food systems in South Africa. On the other side of the ocean, Calcagni (2025) investigates similar forms of resistance to neoliberal and extractivist forces embodied by ANAMURI (Chile’s National Association of Rural and Indigenous Women). ANAMURI is a Chilean organization founded in 1998 with over 10,000 members, including many Indigenous women from Aymara, Colla, Diaguita, and Mapuche communities. As Calcagni (2025) notes, ANAMURI not only organizes against neoliberal and extractivist food systems but also actively politicizes land, water, and seeds as key elements of food sovereignty. In Guatemala, D’Alesandro (2025) uses a multispecies ethnographic fieldwork to write about the Milpa Maya Ixil system, where growing and sharing food has a more-than-human dimension deeply tied to biodiversity, ancestral traditions, and spiritual connection to land and food. In unveiling this system, D’Alesandro calls for recognition and support of the vital carework performed by both humans and nature in sustaining biodiversity.

The contributions on indigenous perspectives offer glimpses into different ways of knowing centered on embodied and relational understandings of the environment. Such perspectives are different from the dominant Western-based scientific approaches. In many industrial agricultural systems, the relationship with nature is often overlooked in favor of profit-oriented practices driven by short-term time horizons and values centered on monetization. Steelman (2025) adds to this conversation by exploring how a model that blends agriculture with therapeutic care—called care farming—can address both animal exploitation and the loss of communal access to food production under capitalism. Through speculative ethnography and fictional vignettes, Steelman (2025) argues that recognizing animals as members of society and expanding care farming can foster interspecies justice and support a post-growth transition. Along similar lines, Barrineau (2025) explores regenerative carbon farming practices that center on the relationship between farmers and soil in Sweden. The author uses poetic inquiry to reflect on these connections, arguing that it opens space for different ways of knowing rather than the strict framework of carbon accounting. This article analyzes two transformative educational methods used with youth in Sevilla and Huelva, Spain, to encourage critical reflection on food practices. Taking different ways of knowing into the pedagogical realm, Lamotte et al. (2025) show, through their participatory research, how multisensory, creative tools foster spaces for action and reflection, supporting social movements toward fairer and more sustainable food systems.

The more-than-human aspect is also addressed by Navarro (2025) in her article, which criticizes the degrowth movement. She argues that for the degrowth movement to achieve ethical coherence, it must challenge the anthropocentric and speciesist norms embedded in mainstream food systems—an aspect that is currently overlooked. Degrowth is also addressed by Pixová et al. (2025) from an alliance-building perspective. Bringing together perspectives from activists, academics, and practitioners, Pixová and colleagues explore barriers, gaps, and solutions to building solidarities and alliances between degrowth and food sovereignty movements.

Zooming in locally, several authors expand on how local initiatives, everyday practices, and democratic decision-making might (or might not) contribute to transforming food systems. Domazet and Lubbock (2025) describe how food self-provisioning supports local autonomy and sustainability in Eastern Europe, offering an alternative to industrial food production. They argue that although often overlooked or framed merely as a response to scarcity, food self-provisioning represents a meaningful shift toward degrowth and sustainable living. Domazet and Lubbock call for politically organized support to strengthen self-provisioning as a transformative force within the broader struggle against capitalist structures and for ecological and social justice. In Switzerland, Steinegger and Faltmann (2025) examine a Community-Supported Agriculture initiative and show how shared experiences and social events help build strong relationships despite physical distance. The authors highlight the importance of emotional, social, and organizational closeness in creating food systems that reduce reliance on industrial agriculture. Also in the Swiss context, Lehner et al. (2025) analyze a national citizens’ assembly work focused on designing food systems. In this process, 80 randomly selected residents participated in a 6-month deliberation to co-create and democratically approve more than 100 food policy recommendations. This direct democratic approach reflects an effort not only to reform food policy but also to empower citizens to envision and enact social-ecological transformation beyond the limits of market-driven systems. In Oaxaca, Mexico, Ismail (2025) studies how it is not just corporate or market forces sustaining neoliberal food systems, but also everyday practices. The author examines how the ban on the sale of ultra-processed foods affects small shop owners, or tienderos. Tienderos continue to sell ultra-processed foods to navigate difficult economic realities that entrench them in a situation in which they unintentionally reinforce neoliberal foodscapes. Ismail concludes that transforming food systems requires addressing everyday material conditions. Everyday practices appear again, not far from Oaxaca, in Prescott, Arizona. Through a visual essay, Czuprynski and Serratos (2024) explore the role of community composting in offering a grassroots alternative to industrial waste management. Combining text and photography, the authors show how composting can de-commodify waste, relocalize food systems, and empower communities to manage organic materials responsibly.

The diverse contributions in this special issue highlight a wide range of practices, values, realities, and epistemologies that challenge the dominant food paradigm. From indigenous perspectives and care farming to degrowth, regenerative soil farming, community composting, and food self-provisioning, these initiatives emphasize relational, multispecies, and place-based approaches to food. They also foreground embodied knowledge, emotional proximity, and democratic participation as key elements for post-growth food systems. Yet, as the next section will show, these transformative efforts often encounter significant structural barriers that threaten their existence, limit their visibility, and constrain their transformative impact.

In investigating the various post-growth initiatives described above, many authors in this special issue also uncovered or confronted key factors that hinder post-growth transformations. Most of the barriers and challenges identified come from the uneven distribution of power and exploitation in the globalized capitalist economy, as well as the patriarchy, colonialism, white supremacy, and imperialism that go hand-in-hand with capitalism.

Many transformative food initiatives encounter significant adversity from the globalized capitalist food system. For instance, the Kesselman and Zukulu (2025) study of the Amadiba foodways in South Africa shows that, because these foodways exist within the national and global food markets, capitalism has continued to permeate the community, reducing interest in traditional ways of living, producing, and relating to food. In addition, infrastructure and resource extraction projects are always a threat to the region and the community’s way of life. In the Global North, Czuprynski and Serrato (2024) found that pressures of profitability, scaling up, and land access pose significant challenges to a community composting initiative in Arizona. Likewise, Barrineau (2025) observes a tension between the long-term repair of soils and the demands of food production. There is pressure to remain profitable, produce high yields, and publish statistics, as well as an obligation to make the amount of carbon sequestered visible. Similarly, Navarro (2025) argues that capitalism has led to the commodification of life, turning animals into biocapital. Concerns about well-being are secondary to efficiency and profit.

As many authors have pointed out, the fact that most people are under pressure to work long hours in money-making ventures is one of the many ways capitalism remains entrenched and resists systemic transformation. In their study of the possibilities for building alliances between the degrowth and food sovereignty movements, Pixová et al. (2025) found that the initiatives lacked the money, time, and other resources necessary to build alliances.

Even when a radical policy is implemented, like banning the sale of ultra-processed foods to kids in Mexico, the inequality and economic insecurity created by capitalism pressures people to focus on money rather than on social and ecological health. As Ismail (2025) found, the various forms of support offered by transnational ultra-processed food companies to small corner stores in Mexico, along with the addictiveness of their products, provide shop owners with a steady income who might otherwise struggle to make a living in a context of high inequality and economic insecurity. As such, the “domestication of neoliberalism” is a key challenge that is often overlooked by political economy analyses that ignore everyday life and practices (Ismail, 2025).

Often, the mainstream system also creates fewer tangible challenges in the form of capitalist logics. In their study of citizens’ assemblies about how the Swiss food system should be changed, Lehner et al. (2025) found that capitalist realism was identified as a key challenge. Capitalist realism refers to the “widespread sense that capitalism is the only viable political and economic system” (Fisher, 2009, p. 2). If participants in citizens’ assemblies assume that capitalism is the only option and are given no opportunity to actively question this assumption, it is hard to expect their policy proposals to address the root causes of unsustainable food systems. Instead, they will tend to design interventions based on the capitalist assumptions they take for granted. Similarly, Lamotte et al. (2025) express concern that alternative pedagogies may lose their political dimensions within the capitalist context, thereby reducing their transformative potential. Meanwhile, Domazet and Lubbock (2025) found that the benefits for food self-provisioning in Eastern Europe remain “unintended”, with practitioners uninterested in acting as a movement or in politicizing their self-provisioning practices. There is still the challenge of giving “a meaningful and progressive voice for a hitherto ‘quiet’ practice” (Domazet & Lubbock, 2025).

There are challenges even when people intentionally step out of the mainstream paradigm. Without a shared vision of fundamental change, it can be challenging to create transformative post-growth alliances among different movements that seem to be working in the same direction. For instance, Pixová et al. (2025) found that building bridges between degrowth and food sovereignty is complicated by the composition of these movements. The degrowth movement is mainly composed of academics and urban-based activists, while the food sovereignty movement is a more diverse, largely agrarian-activist community.

The area of logics and knowledge systems is also where colonialism, racism, and Western supremacy intersect so clearly with global capitalism to present challenges to post-growth transformations. Western science prioritizes “objective” observations that can be quantified over more subjective and qualitative forms of knowledge. For instance, Barrineau (2025) points out that other “ways of knowing” and “seeing with your eyes” are not respected by carbon accounting systems. In her examination of meat consumption and production, Navarro (2025) identifies how degrowth has overlooked the Cartesian dichotomy between humans and the natural world. This view posits human dominance over nature (which is “less-than-human”). Her paper points out that this tendency to dominate and “other” is also related to colonialist-capitalist exploitation, trade, and ownership. Therefore, we must look at all these aspects together.

In exploring how food systems in South Africa can be decolonized for health and sustainability, Roussell & Kesselman’s artistic contribution identifies “ways colonialism disrupted Indigenous people’s relationship with plants, and how these processes and power relations continue to underpin South Africa’s unhealthy and unsustainable food system” (Roussell & Kesselman, 2024). As a case in point, colonialism oppressed the Amadiba ways of living in South Africa, followed by the apartheid regime and its schemes of “betterment”, which forcibly removed people and reorganized land (Kesselman and Zukulu, 2025). Even in studies where barriers are not explicitly mentioned, it is clear that people are fighting to keep sovereignty over their land and food, as pointed out by D’Alesandro’s (2025) multispecies ethnography of the Maya Ixil in Iximulew (Guatemala). These pressures and issues are nearly always in the backdrop. There is also clearly an aspect of patriarchy intertwined with these power systems. In her study of ANAMURI, Calcagni (2025) highlights how the dominant capitalist paradigm perpetuates gender-based injustices by undervaluing care work, reproductive labor, and ecological regeneration. These forms of labor, essential to sustaining life and community, are often dismissed or marginalized within mainstream economic and agricultural models.

The barriers outlined above reveal how deeply entrenched systems of capitalism, colonialism, patriarchy, and Western supremacy continue to shape and constrain efforts toward post-growth food transformation. These challenges manifest not only in structural inequalities and policy limitations but also in everyday practices, knowledge systems, and cultural assumptions that reinforce the status quo. Many of the diverse initiatives explored in this special issue face similar pressures to conform to dominant logics of growth, efficiency, and scalability. Recognizing these obstacles is essential for understanding the complexity of food system transformation. It sets the stage for exploring the creative, collective, and grounded strategies that communities are developing in response.

Post-growth food transformations face a complex web of structural, cultural, and epistemic challenges. Yet across the contributions to this special issue, authors also document a wide range of creative, community-driven, and relational approaches that respond to these challenges in grounded and meaningful ways. These are seeds of hope that offer rich inspiration for overcoming barriers. Three key themes emerge: i) alliance-building, ii) critical food systems literacy, and iii) the intersection of art and activism. Together with solutions that promote democracy, inclusive education, and social well-being, these articles converge on a shared message: the possibility for deep, systemic change.

The most common theme across this collection—and, indeed, across geographical regions—is alliance-building. Kesselman and Zukulu (2025) show how the struggle against colonial oppression in South Africa has strengthened community solidarity. Pixová et al. (2025) emphasize the importance of a shared language and mutual trust for alliance-building between the European degrowth and food sovereignty movements, suggesting that the two need to co-create transformational pathways forward. Domazet and Lubbock (2025) explore the potential of food self-provisioning for post-growth in Eastern Europe, calling it a “movement without a movement”. The two authors stress the need for food self-provisioning to intersect with broader movements such as environmental justice and degrowth, and highlight the importance of cross-class solidarity. Barrineau (2025) underscores the role of grassroots initiatives as sites for relational learning and coalition-building in the context of carbon farming in Sweden. Steinegger and Faltmann (2025) highlight how community-supported agriculture fosters alliances between farmers and consumers by transforming them into “prosumers” through shared space and experience in Switzerland. Finally, Calcagni (2025) illustrates how the Chilean peasant movement ANAMURI acts as a catalyst for socioecological transitions by bridging critical ecofeminism and feminist political ecology.

A similar mix of theory and practice is evident in this special issue regarding critical food systems literacy. Navarro’s (2005) theoretical piece advocates for decentering degrowth discourse from a human-centric view by embracing an anti-speciesist framework—recognizing animals as individuals and valuing nature beyond its utility to humans. In exploring the transformative potential of citizens’ assemblies in Switzerland, Lehner et al. (2025) posit that the assemblies can foster critical food systems literacy by helping participants understand the food system, challenge capitalist realism, and engage in critical pedagogy about political and economic alternatives. Focusing on pedagogical practices, Lamotte et al. (2025) show that participatory and multisensory learning initiatives can foster critical reflection among young people and support broader movements for more just and sustainable food systems. Theory and practice, however, also meet outside the more “academic” space in our collection.

From the start, the special issue was designed to welcome arts and activism as valuable contributions and tools for a post-growth transformation. This part of the collection showcases how artistic practices serve as tools for activism and for alternative ways of knowing, helping break us out of capitalist realism. For example, Barrineau (2025) highlights how poetry creates the space for ambiguity, emotion, and multiple truths, offering a way for farmers to engage with the uncertainties of soil care and critique rigid carbon accounting frameworks. Steelman’s (2025) essay uses speculative fiction to pose open-ended questions and provoke dialogue about political and ecological futures. Finally, Rousell and Kesselman (2024) show how growing indigenous plants traditionally used for food and medicine can empower communities to reclaim food sovereignty and take greater control of their health, highlighting the role of visual storytelling in restoring cultural knowledge and agency.

All these solution-oriented ideas and learnings weave in with systemic, culturally rooted approaches to food system transformation. Kesselman and Zukulu (2025) highlight how the Amadiba community has preserved traditional foodways and ways of living through Indigenous principles and participatory governance, called “Komkhulu”. Ismail (2025) calls attention to the importance of attending “to the intersecting social, economic, and food crises affecting the quotidian livelihoods of people that hinder alternatives to neoliberal food systems” (Ismail 2025, p.8). And while zooming in again on Guatemala, D’Alessandro (2025) illustrates how education grounded in traditional values—as seen in the Maya Ixil community’s efforts to cultivate sovereignty and environmental stewardship—offers pathways for sustaining cultural resilience and resisting capitalist pressures.

Overall, the solutions presented in this special issue reflect a rich tapestry of approaches that challenge dominant food system paradigms through creativity, collaboration, and cultural rootedness. Whether through alliance-building, critical pedagogy, or artistic expression, these initiatives demonstrate that transformation is not only possible but already underway in many communities. They show that food system change is as much about relationships, imagination, and care as it is about policy and economics. Together, these contributions offer a compelling vision for post-growth futures grounded in justice, resilience, and collective action.

Taken together, the contributions in our collection advance a pluriverse for post-growth transformations in food systems by spreading knowledge about relevant initiatives, the challenges they face, and possible ways to overcome them. They also offer valuable lessons on the role of research in societal transformation. Across different geographies and ontologies—from indigenous ways of relating to food and care farming to food sovereignty movements and citizens’ assemblies—authors highlight the importance of embodied knowledge, emotional proximity, relational understanding of food ecologies, and democratic participation. These initiatives challenge dominant paradigms shaped by capitalism, colonialism, patriarchy, and anthropocentrism, offering diverse visions of healthier food systems. At the same time, they reveal how deeply embedded structural and cultural forces continue to constrain transformative potential.

The post-growth initiatives described and analyzed in this special issue consistently encounter challenges. These include entrenched capitalist systems that prioritize profit over social and ecological well-being, often reinforced by daily realities of inequality and economic insecurity. Colonial legacies, such as forced displacement and the erosion of traditional knowledge systems, continue to shape land access and cultural resilience. Patriarchal structures further marginalize care work and ecological regeneration, while dominant Western epistemologies privilege quantifiable, objective knowledge over relational and embodied ways of knowing. Together, these intersecting obstacles constrain the potential for post-growth transformation in food initiatives and underscore the need for systemic change in both practice and scholarship.

Across diverse geographies and socio-cultural contexts, alliance-building, critical food systems literacy, arts and activism, and socio-culturally rooted practices emerge as core pathways forward, helping reimagine how we relate to food, land, and one another. Alliances across post-growth movements—such as degrowth, food sovereignty, ecofeminism, and environmental justice—are essential in a post-growth transition, but require attention to differences in composition, resources, and political orientation. Alliances also require cultivating shared language and trust. Critical food systems literacy is essential to equip communities and individuals to question deeply ingrained capitalist assumptions and engage meaningfully with alternative, transformative models.

We hope that the insights gained from this special issue will motivate and inspire colleagues to further explore how capitalist realism, colonial legacies, and anthropocentric logics constrain transformative potential, and how alternative pedagogies can challenge these paradigms. Artistic and speculative methods, including poetry and visual storytelling, offer powerful tools for engaging uncertainty, restoring cultural knowledge, and fostering emotional and political engagement. Academia, with its role in education and knowledge-creation, must evolve to support methodological pluralism, (re)center marginalized voices, and promote open access and decolonial models of research and pedagogy. This also means facilitating and supporting different ways of knowing that reflect lived experiences and relational understandings of food ecologies, including non-anthropocentric worldviews.

We would like to thank all authors, activists, and artists who contributed to this collection. We thank the Grassroots editorial team for supporting this special issue and for their continuous support, guidance, and patience. We are very grateful to Meenakshi Nair Ambujam from the Grassroots team, for her unwavering commitment, hard work, and help throughout a process that lasted more than three years. We would also like to thank the SEAS CO-FUND postdoctoral programme, partly funded by the European Commission (contract number 101034309), and the University of Bergen for their financial support, particularly funding Claudiu Eduard Nedelciu´s time and the copy-editing process.

Barrineau, S. (2025). Knowing soils–Perspectives beyond growth in carbon farming. Journal of Political Ecology, 32(1): 5919. https://doi.org/10.2458/jpe.5919.

Brock, S., Baker, L., Jekums, A., Ahmed, F., Fernandez, M., Montenegro de Wit, M., Rosado-May, F.J., Ernesto Méndez, V., Anderson, C.R., DeClerck, F., Anderson, M.M., Kerr, R.B., Hoare, B., Wittman, H., Peeters, A., Gubbels, P., Stancu, C., Bellon, S., Lundgren, J.G., Renduchintala, S., Thallam, V., Cady, J.M., & Rogé, P. (2024). Knowledge democratization approaches for food systems transformation. Nature Food, 5(5), 342-345. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43016-024-00966-3.

Calcagni, M. (2025). From peasant women to social change: The politicization of identities and materialities toward socio-ecological transformations. Journal of Political Ecology 32(1): 5930. https://doi.org/10.2458/jpe.5930

Campbell, B. M., Beare, D. J., Bennett, E. M., Hall-Spencer, J. M., Ingram, J. S., Jaramillo, F., Ortiz, R., Ramankutty, N., Sayer, J.A., & Shindell, D. (2017). Agriculture production as a major driver of the Earth system exceeding planetary boundaries. Ecology and society, 22(4). https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-09595-220408.

Czuprynski, Z.J. & Serratos, R.M. (2024). Chop it like it´s hot: community composting for a post-growth society (visual essay). Grassroots. https://grassrootsjpe.org/chop-it-like-its-hot-community-composting-for-a-post-growth-societychop-it-like-its-hot-community/.

D’Alesandro, G. (2025, in press). The Milpa‘s Maya Ixil caretakers, Multispecies biocultural diversity conservation, and designs for more-than-human abundance, Journal of Political Ecology 32(1): 5836 https://doi.org/10.2458/jpe.5836

Domazet, M. & Lubbock, R. (2025) Movement without a movement: Food self-provisioning in Eastern Europe and the Balkans as emergent transformation towards a degrowth mode of living. Journal of Political Ecology 32(1): 5883. https://doi.org/10.2458/jpe.5883.

Elbanna, S., & Child, J. (2023). From ‘publish or perish’ to ‘publish for purpose’. European Management Review, 20(4), 614-618. https://doi.org/10.1111/emre.12618.

Escobar, A. (2015). Degrowth, postdevelopment, and transitions: a preliminary conversation. Sustainability Science, 10(3), 451-462. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-015-0297-5.

Escobar, A., Osterweil, M., & Sharma, K. (2024). Relationality: An emergent politics of life beyond the human. Bloomsbury Publishing.

Feola, G. (2025). Postgrowth food systems: Critique, visions, pathways. Degrowth Journal, Volume 3 (2025). https://www.degrowthjournal.org/publications/2025-01-27-postgrowth-food-systems-critique-visions-pathways/.

Fisher, M. (2009). Capitalist realism: Is there no alternative? Zero Books.

Gibson, M., Mason-D’Croz, D., Norberg, A., Conti, C., Boa Alvarado, M., & Herrero, M. (2025). Degrowth as a plausible pathway for food systems transformation. Nature Food, 6(1), 19–24. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43016-024-01108-5.

Guerrero Lara, L., van Oers, L., Smessaert, J., Spanier, J., Raj, G., & Feola, G. (2023). Degrowth and agri-food systems: A research agenda for the critical social sciences. Sustainability Science, 18(4), 1579–1594. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-022-01276-y.

Ismail, A. (2025). Domesticating neoliberal foodscapes: An everyday approach to understanding food system transitions in Oaxaca, Mexico. Journal of Political Ecology, 32(1): 5843. https://doi.org/10.2458/jpe.5843.

Jacobi, J., Villavicencio Valdez, G. V., & Benabderrazik, K. (2021). Towards political ecologies of food. Nature Food, 2(11), 835-837. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43016-021-00404-8.

Kallis, G., Hickel, J., O’Neill, D. W., Jackson, T., Victor, P. A., Raworth, K., Schot, J.B., Steinberger, J.K., & Ürge-Vorsatz, D. (2025). Post-growth: the science of wellbeing within planetary boundaries. The lancet planetary health, 9(1), e62-e78. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2542-5196(24)00310-3.

Kesselman, B. & Zukulu, S. (2025). Traditional foodways of the Amadiba: A struggle for indigenous food sovereignty in Mpondoland, South Africa. Journal of Political Ecology, 32(1): 5933. https://doi.org/10.2458/jpe.5933.

Lamotte, L., Ramos-Ballesteros, P., Peña-Cabra, R. & Mathez-Stiefel, S. (2025). ¿Cómo concientizar a lxs

jóvenes sobre sus prácticas alimentarias? Una mirada crítica desde metodologías de pedagogía transformadora en Andalucía, España. Journal of Political Ecology, 32(1): 5832. https://doi.org/10.2458/jpe.5832.

Latouche, S. (2009). Farewell to growth. Polity.

Lehner, I., Amos, S., Mathys, P. & Jacobi, J. (2025). From the ground up: Exploring the potential contribution of citizens’ assemblies in radical food-system transformation. Journal of Political Ecology, 32(1): 5842. https://doi.org/10.2458/jpe.5842.

McGreevy, S.R., Rupprecht, C.D.D., Niles, D.,Wiek, A., Carolan, M., Kallis, G., Kantamaturapoj, K., Mangnus, A., Jehlička, P., Taherzadeh, O., Sahakian, M., Chabay, I., Colby, A., Vivero-Pol, J., Chaudhuri, R., Spiegelberg, M., Kobayashi, M., Balázs, B., Tsuchiya, K., Nicholls, C., Tanaka, K., Vervoort, J., Akitsu, M., Mallee, H., Ota, K., Shinkai, R., Khadse, A., Tamura, N., Abe, K., Altieri, M., Sato, Y., Tachikawa, M.(2022) Sustainable agrifood systems for a post-growth world. Nature Sustainability 5: 1011–1017. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-022-00933-5

Navarro, E. (2025). “Meat-me”: From flesh machines to individualities. A case for an anti-speciesist degrowth. Journal of Political Ecology, 32(1): 5834. https://doi.org/10.2458/jpe.5834.

Neo, H., & Emel, J. (2017). Geographies of meat: Politics, economy and culture. Routledge.

Parrique, T. (2019). The political economy of degrowth (Doctoral dissertation, Université Clermont Auvergne [2017-2020]; Stockholms universitet). https://theses.hal.science/tel-02499463/.

Patel, R. (2013). The long green revolution. The Journal of Peasant Studies, 40(1), 1-63. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2012.719224.

Patel, R. (2025). Counter-hegemony and polycrisis I: how to eat and how to think. The Journal of Peasant Studies, 1-32. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2025.2499271.

Pixová, M., Spanier, J., Guerrero Lara, L., Smessaert, J., Sandwell, K., Strenchock, L., Lehner, I., Feist, J., Reichelt, L. & Plank, C. (2025). Building solidarities and alliances between degrowth and food sovereignty movements. Journal of Political Ecology, 32(1): 5841. https://doi.org/10.2458/jpe.5841.

Rousell, C. & Kesselman, B. (2024). How colonialism disrupts and continues to disrupt people’s relationships with plants (visual essay). Grassroots. https://grassrootsjpe.org/how-colonialism-disrupted-and-continues-to-disrupt-peoples-relationship-with-plants/.

Said, E. W. (1994). Representations of the intellectual: The 1993 Reith Lectures. Vintage, London.

Shiva, V. (1991). The violence of the green revolution: third world agriculture, ecology and politics. Zed Books.

Shore, C., & Wright, S. (2024). Audit culture: How indicators and rankings are reshaping the world. Pluto Press.

Smith, K. (2010). Research, policy and funding–academic treadmills and the squeeze on intellectual spaces. The British Journal of Sociology, 61(1), 176-195. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-4446.2009.01307.x.

Steelman, T. (2025). City of sanctuary: Exploring multispecies democracy in a post-growth food future. Journal of Political Ecology, 32(1): 5850. https://doi.org/10.2458/jpe.5850.

Steinegger, S. & Faltmann, N. K. (2025). Proximity despite distance? A community-supported agriculture initiative across rural mountain and urban areas in Switzerland. Journal of Political Ecology, 32(1): 5944. https://doi.org/10.2458/jpe.5944.